A league of extraordinary gentlemen

A discreet army of shop assistants is educating India’s newly affluent about the finer nuances of luxe. Hindol sengupta plays fly on the wall.

IT'S A HUMID DELHI EVENING. Around 80 businessmen and professionals sit at banquet tables in the ITC Sheraton, while Sandeep Arora explains how to appreciate whisky. Arora, who heads spirits consultancy Spiritual, has been holding these classes, sponsored by whisky labels. “Hold the glass like a mistress, not a wife. Then sniff. Let the aroma tease you and slowly open up,” says Arora, as he flits between tables. He pulls in 1,600 people annually. Though he’s been doing this for the last eight years, it’s only been in the last four that the number of attendees have swelled. He reckons that they have been growing by 25% to 30% year on year.

India is a growing spirits market and people are eager to know how best to enjoy single malts. That’s where people like Arora, who help the new rich become part of the elite, fit in.

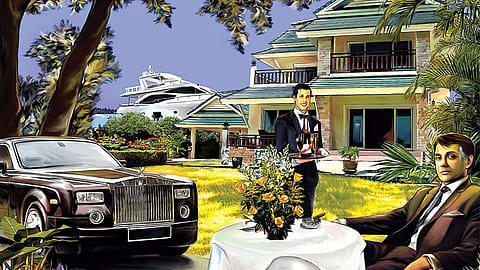

Fuelled by an economy on steroids, as more Indians buy some of the world’s most expensive products, an entire army of assistants is helping them with the nuances of luxe. Once the preserve of maharajas, and then very wealthy businessmen, luxury is no longer a privilege. According to a 2009-10 survey by Merrill Lynch Global Wealth Management and Capgemini, India has 126,700 dollar-millionaires. Purveyors of the good life believe the actual numbers are considerably higher.

For first-timers, though, buying is just the beginning. How to maintain a Rs 2.5 crore Rolls-Royce or button a Rs 1 lakh Canali suit is far more important. Enter the in-store equerry.

Having sold 50 cars in India in two years, Pankaj Sharma, the Rolls-Royce salesman in Delhi, knows best. Gesturing elegantly, and always in control, he explains the minutiae of ownership. Walk-in customers almost invariably ask about the car’s mileage. Given that some end up buying the car, Sharma’s job is to direct their attention to other features—the grand interiors, for example. The Spirit of Ecstasy is displayed on the bonnet only when the master (or ‘King’, in Rolls-speak) is in the car, he says.

The marquee label has begun training chauffeurs in India. Sanjeev Hazari, general manager, Rolls-Royce India, says that all cars need to be explained to potential buyers, “whether it is a Rolls or any other”. His training prevents him from saying more.

One of the challenges of selling high-end brands in India is the environment in which they are sold. Luxury stores are sometimes surrounded by relatively pedestrian outlets. While the luxury experience is open to a more varied audience, many of whom become buyers, it also means walking that fine line between preserving brand exclusivity and not appearing high-handed.

Within seconds of picking up a Rs 15 lakh watch, the customer at the Vacheron Constantin store asks how many years it is guaranteed for. The store assistant, in a spiffy suit and perfect coiffure, says, “It comes with a lifetime guarantee, sir.”

The staff at luxe stores here is sensitised in a slightly different way. On the surface, the training is the same in Delhi and, say, Paris. But shop assistants privately admit they are coached, among other things, on what watch to wear. “What if the customer is wearing one less expensive than mine? He will think, ‘You’re telling me how rich you are?’ And what if he is wearing the same brand? That’s equally bad,” says Sharma.

He rolls his sleeve up to reveal his watch. “See? Titan. Always.”

Tikka Shatrujit Singh straddles both worlds. As advisor to Louis Vuitton chairman Yves Carcelle, he promotes the brand in India. As scion of the former royal family of Kapurthala, he is more familiar with the brand than many clients. He argues that the way forward here is to marry the mystique of luxe with its possibilities of daily use. “We emphasise that the Louis Vuitton valise was once used by maharajas; but we also convey that it is good for everyday use. As long as you don’t leave it out in the sun.”

(INR CR)

By contrast, Sandeep Bhatt, COO, Religare Voyages, India’s only private jet management and advisory service, could even crash a few aspirations. While he educates owners about the limits of their aircraft, he also points out why it’s not always advisable to own one. “Some people don’t understand that a large business jet cannot land on the small airfields that are so common in India,” says Bhatt.

Back at the ITC Sheraton, Arora’s audience is just warming up. A member casually inspects the label on a whisky bottle. Almost, as if on cue, Arora says: “Appreciation is about the palate, not the wallet.”