Kolkata’s chippendale

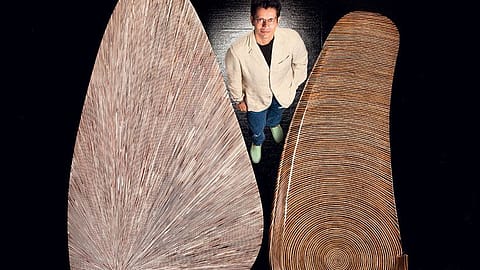

Jay Gorsia has built a luxury furniture business with a manic obsession for detail. And he doesn’t want to go mass.

NOT A SINGLE HAMMER. A furniture factory, and there’s no sawdust in the air, no wood shavings underfoot. And yes, no hammer in sight. It looks more like a hospital or high-tech R&D lab than a furniture workshop. There are machines to plane the wood, machines to dry the planks, and even machines to suck up the fine spray from paint nozzles so it says they don’t emphasise “international quality”. Soon after he set up shop, he brought master woodcarver Ian Agrell from California to train his team.

What does Gorsia look for when he hires? Artistic sensibility, of course. But equally, he looks for people who reflect his own almost obsessive quest for perfection.

Gorsia says he picked up that sort of attention to detail from legendary hotelier P.R.S. ‘Biki’ Oberoi, whom he met in 1992. The hotelier was interested in land in Marbella, Spain, owned by Gorsia’s friends, and Gorsia accompanied him on that trip. “In Marbella, we would visit different hotels and he’d check out every single little detail, like tiles in the bathroom to see how they fit and reflected light. He does everything himself when he doesn’t have to.”

"IF JAY'S MAKING YOU A CHAIR" he will think. Is it a cocktail chair? Then he will make it cushy enough to sink in and enjoy the drink. If it’s an office chair, he’ll ensure there’s support for the back,” says Talwar, for whom Gorsia designed and furnished office and home spaces in Delhi. “It’s not just a pretty piece of wood for him.”

While Talwar says he hired Gorsia because of the designer’s functional approach to luxury, for Kajaria, Gorsia has stylish answers to problems. “We have a three-storey home in Alipore and wanted to brighten it up. Jay cut a hole through the building and placed large windows throughout. So natural light floods the place now.”

Gorsia recalls how he walked into a premium Italian store in Dubai with the owners of Anmol Biscuits, a Kolkata-based company. “They wanted to buy some 20 pieces of furniture right there, and I had to explain that it was commercial stuff.” That night, when they went for dinner to Cavalli Club Dubai, a trendy hot spot, they saw similar furniture there. “They got the point,” says Gorsia. “They didn’t want their home to look like a high-end nightclub.” They chose Gorsia’s designs.

Gorsia’s is not a starving artist-in-a-garret story. His family ran a successful stevedoring business and he could have signed on there. But he wanted to build things. So he went to the Pratt Institute in New York to study architecture and design. He worked for a while in the U.S. but wanted to go back to Kolkata and set up on his own. By 1993, he had accumulated Rs 60 lakh by divesting his share in the family business and pooling his savings. He set up his studio in Kolkata’s upmarket Judges Court Road and began making furniture at his garage with three craftsmen and secondhand machinery imported from the U.S. The early days weren’t easy. “Awareness about high-life interiors was low. The moneyed classes didn’t quite get it then,” he says. He still recalls a client who wanted to use tiles that cost $200 (Rs 9,498) in a bathroom; Gorsia intended them for one of the main rooms.

Finding clients, even those with more money than taste, was an uphill task. That’s when Gorsia’s contacts came in handy. Oberoi helped the designer snag some major business in India, including a contract to make the furniture for the Oberoi Grand in Kolkata.

Today, he takes orders only by appointment. He doesn’t have a store and ships from his factory. And he insists on sourcing all the raw material himself. Thumbing through a swatch of veneers embedded with materials such as shells and fossilised wood (“It’s the next big thing”), he talks about his next trip to source materials, but refuses to say where.

Asked to define himself, Gorsia says he’s an architect who designs interiors and furniture based on the fundamentals of architecture. His office, which resembles a glass gazebo, has a mini pool and a pond with koi carp. “I like to work the way I live, and that’s what I communicate to my clients.”