Why Hamleys is Reliance’s preferred toy

India’s richest man Mukesh Ambani bought Hamleys for about $88 mln. In the iconic toys brand, Reliance has a retail business that is expanding rapidly.

There’s a new royal baby in Britain, and chances are, he’ll grow up playing with Hamleys toys. The royal family, it is said, are loyal customers of this centuries-old British brand. But, like most kids, the royal one too is likely to break his toys, howl for a couple of minutes, and move on to the next, brighter, shinier one. That’s the way it goes, and that’s why toy makers and sellers are likely to always have a market.

Yet, the business of selling toys is often overlooked. Take India’s largest retailer, Reliance Retail. It is mostly identified with its apparel stores, electronics outlets, and supermarkets. But besides these big-ticket businesses, Reliance—whose retail businesses reported a combined annual revenue of Rs 33,765 crore last financial year—under a franchise agreement, operates in India the toy stores of Hamleys. If the number of new stores is a marker, it is a business that is doing well. Early this year, Reliance opened the 50th Hamleys store in India—in Amritsar. There were only two five years ago; in fact, the number of Hamleys stores in India has doubled in the last 15 months.

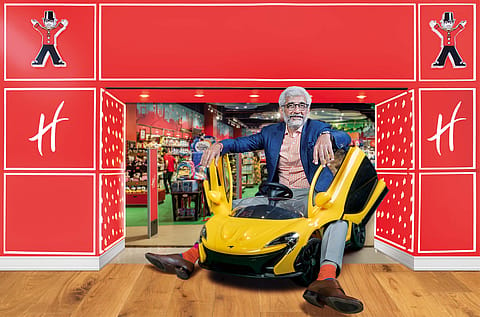

Darshan Mehta, CEO of Reliance Brands, says it is only the beginning of an aggressive expansion—he foresees 100 Hamleys stores in India by 2020. “We feel that we have perfected a business model that was so far lacking in the toys business,” says Mehta. Reliance Brands is a subset of Reliance’s retail businesses under which single-branded outlets such as Hamleys operate. Reliance also runs the India stores of Marks & Spencer, Superdry, and MUJI, among others.

Hamleys’ expansion seems logical if one were to look at India’s population. The last census put the number of children under the age of 11 at just under 300 million. And by all estimates, it is a country that is growing younger.

But selling toys in India is not just a matter of opening a swanky store. The market, to begin with, is largely unorganised—crowded by many small- and medium-sized toymakers and their retailers. This disparate and informal nature of toymaking and distribution makes it hard to put a number on the size of the market. Many market research firms consider toys and games—video games and the like— together in their study. Manish Kukreja, president of the All India Toy Manufacturers’ Association, an industry body, says India’s toy market is Rs 4,000 crore worth annually. The central government’s National Productivity Council, in a report, had a more optimistic estimate of Rs 8,000 crore, of which over 60% it said is accounted for by the unorganised sector. If one were to take the halfway mark, the average expenditure on toys for a child under the age of 11 is Rs 200 in India.

In that context, Hamleys’ growth looks more like an aberration; even a soap bubbles gun at its store costs over Rs 800. Of course, a brand such as Hamleys addresses a different India: the upwardly mobile Indian middle-class.

“Despite its [India’s] large market size, there were only 4,000 to 4,500 retail shops that stocked toys for a long time and it didn’t make any sense for the big toy companies to set up big location operations,” says Amit Kararia, senior regional sales manager, South Asia of Lego—and the overseer of the Indian market for the Danish company known for its interlocking brick toys.

Recommended Stories

Lego has so far relied on what could be termed an export-and-forget model in India. But rising interest in international toy brands in India has made the company take notice—it has appointed a local team to promote products tailored for the country, and, last year, ran a “My First Lego” campaign to nudge first-time buyers.

Lego’s measured approach is perhaps justified considering the experience of international brands in India. Mattel, the U.S. toymaker best known for its Barbie dolls and Hot Wheels toys, had a joint venture with Dilip Piramal’s Blow Plast since the 1980s to sell its toys in India. The partnership prematurely ended in 1999.

In 2001, Mahindra & Mahindra, makers of farm equipment and commercial and passenger vehicles, became a distributor of Lego. M&M is no longer in the business of selling toys—its BabyOye stores were acquired by Brainbees Solutions, the company that operates FirstCry stores, which among other baby products, sell toys. Mahindra, however, holds a stake in Brainbees .

Yet, Hamleys stands apart. In stores run by FirstCry or retail chains such as Lifestyle or Big Bazaar you would find more clothes than toys. A closer competition is Funskool of the MRF group, which makes and sells toys in India. Funskool says it operates 20 stores in India.

(INR CR)

Outnumbering competitors on store count does not necessarily mean the business is booming. Is Hamleys’ expansion a result of high demand for its toys or an ambitious bet in the expectation of an inflection point? It is difficult to tell. The business doesn’t publish standalone financial numbers, instead, its sales get consolidated with several other brands of Reliance Brands, which reported sales of Rs 282 crore and a loss of Rs 28 crore in 2017. The company, however, says that over the years the average unit price of toys stocked in its stores has gone up from Rs 593 to Rs 965, and the stock of products priced over Rs 10,000 has doubled from 3%. It says the customers spend an average of Rs 1,750 in its stores.

But as Hamleys expands, Reliance is evolving its approach. The company previously preferred only large stores, upwards of 10,000 square feet, as it wanted to deliver the same experience to kids everywhere. Today, though, it runs four types of Hamelys stores: large flagship stores, express, regular, and airport stores. The flagship stores like the one in Mumbai will be limited to urban locations with high disposable income and function like modernday experience stores, whereas the airport stores are typically 500 sq. ft outlets that hope to make a quick business from travellers. Mehta of Reliance Brands says the airport stores are doing brisk business.

The company is also reaching out to a wider audience. Today, 17 of the 50 stores are in smaller cities and towns. Manu Sharma, of Reliance Brands, says: “Just as much as our stores are a new experience to customers in smaller cities, we are also learning as their consumption patterns are quite different from the metros.” He says traditional board games have a comparatively high demand in small cities.

Hamleys India doesn’t make toys but brands those sourced from manufacturers—the India entity has the right to source toys from anywhere in the world and brand them Hamleys in the domestic market. Though it also sells toys from companies such as Lego and Mattel, Hamleys in India is emphasising on in-house or exclusive toys as they offer better profit margins. Under the agreement, Reliance pays Hamleys’ parent company a royalty on its overall revenue. Since 2015, Hamleys is owned by Hong Kong-listed Chinese footwear retailer C.banner.

Exclusive toys have better profit margin, says Reliance Brands. “We had to work out different permutations and combinations on the kind of products we sell in each store. We have now perfected the process,” says Karandeep Singh, business head, Reliance Brands in charge of Hamleys.

Yet, no matter how thought-out a retailer’s strategy is, second-guessing the mind of, say, a six-year-old is not easy. Would the soap bubbles gun that intrigued her last time be of any significance to her now? It’s anybody’s guess. Take the fidget spinner, a small hand-held spinning device originally designed for those suffering from anxiety, which became the most popular toy last year. Did any major toymaker foresee this trend? How much would have the innocuous spinner harmed their revenue? The inability to predict the fickle minds of the young is perhaps the challenge for toymakers and retailers such as Hamleys.

Hamleys’ wider presence, however, gives it the ability to sway the market and cope with that challenge. “We are entrusted with holding the attention of a kid for the first 11 years of his life which is a pretty long period, and the trick is to keep the excitement going non-stop,” says Mehta.

There are other challenges, too. Toys are now subject to 12% tax after India implemented the Goods and Service Tax (GST), as against the 5% VAT and zero excise duty on manufacturing. Also, the new mandate for toys to adhere to the Bureau of India Standards (BIS)—introduced late last year—means importers have to get every toy sample tested in approved laboratories. Though widely seen as a measure to control the quality of toys being imported in large quantities from China—a welcome move—it does add stress to the industry. Mehta, though, says the increased tax, or the new rules, is not a major concern. He says that there are lots of “inefficient costs in the business” due to its small size, and as the market grows such expenditure will reduce. He also adds that Hamleys promotes half a dozen local toy and game manufacturers.

The fact that there is no periodical spike in demand for toys—in contrast to apparel which follows seasons—also means a retailer could be left with reduced working capital in case of unsold stock.

Also, other global toymakers and retailers have taken a renewed interest in India—Mattel, and Hasbro, the maker of Transformers toys, have either set up a new subsidiary in India or spruced up existing local operations.

Then there is the threat posed by ecommerce. Caught in the discount war between Amazon and supermarket chains such as Walmart, Toys “R” Us—a U.S. based toy seller that consultancy firm Deloitte says is among the top 100 retailers of the world—declared bankruptcy this summer and is shuttering all its U.S. and British stores (Read more on Toys “R” Us on page 40). In India, Amazon and homegrown e-commerce giant Flipkart, pose a similar threat to toy retailers.

Reliance Brands, however, is confident. Mehta says the company has not “even scratched the surface of the opportunity”, and says the entry of more organised players in India will only spur growth.

That and more broken toys and crying babies.

( The article was originally published in the May, 2018 issue of the magazine. )