The anatomy of a successful mall

Why some get it right while most others don’t.

Then there are the popular myths. Underhill says, “Some say that if a mall is too clean and well lit, Indians consider it expensive. That simply isn’t true. Indian consumers deserve better shopping environments. In a country that gave us the Taj Mahal, we are still looking for the ultimate shopping centre.” Till it is found, malls will keep flagging down cars to find investment.

Demand, though, will remain high for good-quality spaces, now that the government has allowed 100% foreign direct investment in single brand retail. Also, urban India has massive gaps in quality retail space, such as the affluent Greater Kailash in Delhi or Matunga in Mumbai which lack high-end shopping destinations, as do tier II and tier III cities.

Then there’s design. Ro Shroff, principal architect at Seattle-based design firm Callison, travels monthly to India. He believes new malls are learning from Inorbit and CityWalk which were imagined by international architects. “International design firms tend to understand the science of shopping a lot better and design accordingly,” he says.

“Managing malls is not the core business of DLF or Unitech and that is why there are opportunities for mall management firms,” says Dungarwal, who also runs a mall management firm. But apart from Propcare, Property Zone, and JLL, most of those that call themselves mall management firms are actually engaged in facilities management.

Some bad malls need rethinking. When asked what could be done about Delhi’s MGF Metropolitan Mall, which features bad design, and sold space, Underhill says tersely: “Bulldoze it”. Not everyone has such drastic solutions. Several firms have cropped up ready to help get these malls back on their feet and ensure that future projects don’t repeat mistakes.

BUT FOR ALL THAT MALLS DO right, India’s best don’t compare with the best globally. Arvind Singhal, chairman of Technopak Advisors, believes that India’s most popular are those that have used common sense best from a group of otherwise bad shopping centres. For a country that requires at least 20 million sq. ft. of retail space added annually (India’s retail market is estimated to be worth between $500 billion and $550 billion and growing at 9%), the opportunities to create international benchmarks, such as Westfield Shopping Centre, were obvious. But few, he says, have been taken.

Well-lit and safe parking facilities are another crucial factor, especially for women. It is generally acknowledged that when women feel comfortable and frequent a place, children and men follow. As Shona Taneja, vice president and director at India market entry advisory firm Tecnova, says: “It makes a huge difference when I drive out of CityWalk and see women around, even after a late night movie in an unsafe city like Delhi.” CityWalk has nearly 260 CCTV cameras and women attendants. And, of course, parking charges—as high as Rs 50 on weekends—are a source of easy revenue for malls. Some malls in Mumbai are estimated to make as much as Rs 35 lakh a month from parking fees alone.

Hence, innovative promotions. In April, Forum allowed local fine arts college students to create sculptures and paintings, as mall visitors watched. Inorbit organised boxing tourneys, talent shows, and opened the mall at 6 a.m. for those who wanted to walk in a cleaner environment than Mumbai’s streets. CityWalk gave Delhi’s budding entrepreneurs a chance to showcase their wares—knick-knacks, jams, etc.—with a ‘flea market’. Such activities create engagement with the local community. They make business sense too. Beyond Squarefeet’s Dungarwal says more than 60% of business comes from patrons who live within a 5 kilometre radius.

In the U.S., malls were a product of suburban living and were often community centres for locals. In India, however, malls are designed to create an island where Indians are welcome, but India, with its chaos and confusion, is not. The local mall, therefore, is a place to socialise and at the same time stay cocooned in airconditioned comfort. It is also where you can shop. The developer needs to balance the two.

Paco Underhill, author of Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping and Call of the Mall: The Geography of Shopping, and founder of consumer behaviour research firm Envirosell, says, “In emerging markets, a mall is more than a shopping centre. It is a centre for socialising. You’ll see far more girls in high heels compared to those in rubber-soled shoes in a shopping mall in an emerging market.”

Promoting the shopping centre within its locality is another part of effective mall management. In India, as in many emerging markets, malls tend to have purposes beyond shopping.

(INR CR)

Intertwined with this is the question of getting the right brand mix. The brands that people wanted in 2004 may not be the same in 2012. It is up to the mall manager to keep track of consumer behaviour, and house brands that best reflect what their target audience wants. Hence, operators build in contract clauses that allow them to ask underperforming shops to move on. Inorbit, for example, has seen a 7% churn over the years. “Churn helps keep the mall fresh and consumers discover new stores when they shop,” explains Bhatija. “It works for both malls and retailers.”

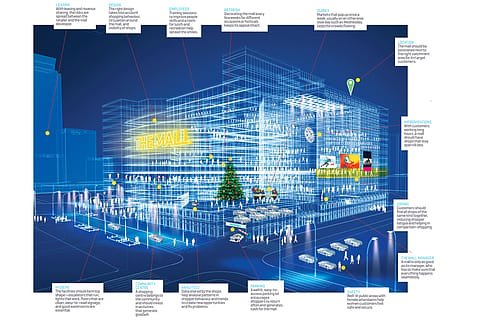

“Inorbit, Forum, and CityWalk have succeeded in clearly zoning specific areas. In any of these malls you know exactly where to buy shoes,” says Harminder Sahni, managing director, Wazir Advisors, a company that helps firms mould their retail strategy.

The developers also dealt with clustering similar retailers, called “zoning” in mall lingo. This ensures that shops selling similar products or services are in the same part of the mall so that consumers don’t have to go far to compare. This mirrors the traditional Indian bazaar where entire streets are devoted to one type of item, say silver jewellery in one part of Delhi’s Chandni Chowk or electronics on Mumbai’s Lamington Road.

“Grocery retail or even coffee shops don’t run on the highest margins and their ability to pay rent is less than, say, apparel retailers. That doesn’t mean that in Inorbit or CityWalk, a Barista or a Food Bazaar is tucked into an insignificant corner,” says Sharma. “We designed our mall with the woman in mind. We didn’t want her dragging her grocery bags throughout the mall. So we put Food Bazaar near an exit. It may pay a lower rent than the others next to it, but our blended rate [the total rent of all shops in a mall] makes up for it.”

This is echoed by Arjun Sharma, director, CityWalk. “Because my partners and I came from a travel and tourism background and had no experience with real estate projects, we made the decision that we would not treat our mall as a real estate asset.” He and his team travelled extensively to the best malls globally, such as Westfield Shopping Centre in London, and hired a number of experts on shopper behaviour to understand industry best practices. He believes the time and money invested was excellent use of both.

“TODAY, WITH A MALL, you are no longer a mere builder. You are a developer too,” says Bijou Kurien, chief executive, lifestyle, Reliance Retail, whose portfolio includes Marks & Spencer, Diesel, Timberland, and Reliance Jewels.

Because builders stand to gain from sales, they track the number of visitors to shops. Some even have remote access to cash counters. This gives them a picture of overall sales trends, which is then shared with retailers to solve problems that the latter might otherwise miss. For instance, when the management team at CityWalk noticed that shoe sales fell in March, it advised shoe shops to keep discounts going through the month to attract those who were busy with children’s exams. As Kishore Bhatija, CEO and director at Inorbit Malls, Mumbai, points out, a good mall manager is like a good general manager of a hotel who can make or break the business.

In this system, everyone wins. Since mall management is invested in improving sales, “most retailers are happy to pay a fixed percentage of sales,” says Shubhranshu Pani, managing director, retail services, at real estate advisory Jones Lang LaSalle India.

It was only a matter of time before builders realised they could profit more by renting out floor space and asking for a share in revenue. “Globally, the lease-plus-part-of-income model is the accepted standard. Selling space hasn’t worked anywhere,” says S. Raghunandan, CEO retail, Prestige Group, which runs Forum.

Ansal Plaza and most malls that came up later, sold space to retailers. This meant the builder did not maintain the facilities and buyers resold shops, playing havoc with the retail mix.

Mall management helps malls balance an understanding of consumer behaviour with profiting from every square foot. It’s basic: The mall cannot be a distinct entity, separate from the shops within it. Each has to be interested in the other’s well-being for mutual success. Classic failures are those malls which sold floor space to shops and restaurants. In the early 2000s, Crossroads in Mumbai and Ansal Plaza in Delhi were hugely popular. They were among the country’s earliest malls and people flocked to them for novelty value. But 12 years on, Ansal Plaza is empty; most shops wear a slightly seedy air, and the parking lot is used by hundreds of people who never enter the mall.

Susil Dungarwal, chief mall mechanic of advisory firm Beyond Squarefeet (which deals with clients such as Bangalore’s Forum and Mumbai’s Nirmal Lifestyles), says most malls get the basics wrong, with poor design, a bad mix of brands, and lack of differentiation. On ‘Malls Road’ everyone loses due to oversupply.

MOST PRECEPTS OF GOOD MALL management sound like common sense: well-known shops and brands, well-planned amenities, safe and adequate parking, popular activities, etc.

Location near an upwardly mobile neighbourhood used to be of primary importance for a mall. But people are now willing to travel more than 10 kilometres to visit a popular mall. That’s where mall management makes a difference.

What are these dozen or so successful malls doing differently? The popular real estate truism says location is all that matters. But in Delhi alone, there are several examples of failed malls right next to hugely successful ones. The capital’s Select CityWalk is crammed even on Wednesdays (traditionally the leanest business day for malls), while the MGF Metropolitan Mall right next to it is often eerily empty. There’s an entire stretch of M.G. Road in neighbouring Gurgaon that’s known locally as Malls Road thanks to almost a dozen glass and steel shopping centres that line it, but they are hardly as successful as expected even five years ago.

The Great Adventure Mall joins 350-plus malls in the country today. Another 300 are in the works. But barely 12 to 15 make money for retailers and builders—a sad fact for a market that is the biggest global retail investment opportunity outside China.

For a minimum investment of Rs 50 lakh, this method of selling space seems remarkably haphazard. But it is this behaviour that characterises the growth of malls in India. There’s too much money at stake; an estimated $10 billion (Rs 52,470 crore) has been invested in mall construction over the past 15 years when the retail boom happened.

ON A SWELTERING DAY IN April, most cars on the road connecting Delhi to Greater Noida ignore the two formally-dressed young men waving brochures. One stops and is greeted with grateful enthusiasm: “Sir, do you want to invest in a mall?” They are employees of the Great Adventure Mall, a shopping centre being built half a kilometre off the upcoming Yamuna Expressway.