The big picture

Collecting miniatures seems to be what separates art aficionados from the arriviste. Price is no barrier, but supply is a problem.

the shimmering light of an imposing chandelier that once adorned the ceiling of a palace of a Nizam of Hyderabad illuminates the numerous paintings (from a Raja Ravi Varma to an Abdur Rahman Chughtai) that cover the walls in the Lutyens Delhi home of Vivek C. Burman, chairman emeritus, Dabur India. Amid large canvases, and art pieces, including a lamp from Rabindranath Tagore’s house, hangs a set of four glowing miniature paintings set in golden frames.

I ask about the provenance of these, but just as Burman is about to reply, three men stagger into the room with an enormous package. Burman is immediately by their side, explaining exactly where he wants them to set the package down. Under his watchful eye, the men lift out the contents: 16 gorgeous miniature paintings set on a mirror-like surface.

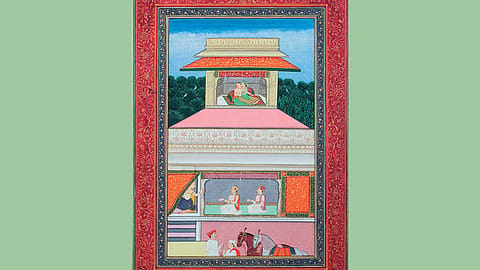

These are among the latest additions to Burman’s eclectic collection of 50 or 60 miniatures, spanning all ages and schools, and bought for anything from Rs 30,000 to Rs 12 lakh. “If a painting appeals to me, I buy,” he says simply. One of the chief reasons for this kind of almost random buying is because miniature paintings are the art world’s hidden gems, and small as demand is, supply is even less. Some of the earliest paintings date back to the 11th century Pala school of miniatures, which drew inspiration from Buddhism. The Western Indian style of Gujarat, Rajasthan, and parts of Madhya Pradesh (the Malwa region) was dominant between the 12th and 16th centuries. In the 15th century, the Persian style started influencing western Indian art.

The Persian style of miniature painting is described in exquisite detail in what author Orhan Pamuk calls his “most colourful and optimistic book”, My Name is Red. “I painted scalloped Chinese-style clouds, clusters of overlapping vines and forests of colour that hid gazelles, galleys, sultans, trees, palaces, horses and hunters,” he writes.

This style had a huge impact on the Mughal school. “I like Mughal miniatures the most. I don’t buy these for investment, I just like collecting them,” says Burman. He’s not alone; art collectors around the world want to own Mughal miniatures. “Most original Indian miniature paintings are in museums, auction houses, or private collections abroad. During the Emergency [1975-77], a lot of art was sold abroad for a song due to regressive government policies. Today their value is in crores,” says Brajraj Singh, the maharaja of Kishangarh, who collects miniatures, and whose erstwhile kingdom lent its name to a school of painting.

Collecting miniatures seems to be what separates the art aficionado from the arriviste, with corporate India’s royalty expanding their collections to include these small gems. Tina Ambani, wife of Anil Dhirubhai Ambani Group chairman Anil Ambani, has been promoting miniatures through her Harmony Art Foundation shows. In 2009, the theme of her show was traditional Indian miniatures, with 300 works by 40 artists on display. In 2011 she held a contemporary miniature art show called ‘Fabular Bodies: New Narratives in the Art of the Miniature’.

Money is evidently secondary; all the collectors Fortune India spoke with say they acquire miniatures for the joy they get rather than a potential rise in value. “Some paintings have been done so finely that one can even see the blood vessels in the eyes of the subject with a magnifying glass,” says S. Shakir Ali, a Jaipur-based miniaturist and Padma Shri awardee.

On the flip side, this kind of buying means that fake paintings enter the scene. Fakes, explains Singh, are sometimes so skilful that even experts can get taken in. He tells of a thriving business which uses only the paper from the particular era. Many get taken in by the age of the paper and don’t notice that the painting is recent. “There is a dearth of experts and sometimes even the best get confused,” says Singh.

One of the problems with a niche set of buyers is that contemporary artists see no future in this style. “The market for miniature paintings is very small compared with that for [larger] paintings,” says Sunaina Anand, director, Art Alive Gallery, Delhi. But with more people like Burman snapping up miniatures, the small market could well get bigger.