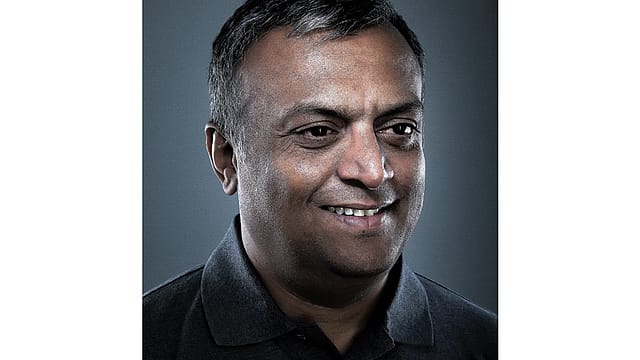

Indian pharma’s maverick thinker

ADVERTISEMENT

Bengaluru. Monday. 8.30 a.m. I’m waiting to meet Arun Kumar, CEO of pharmaceuticals company Strides Shasun, which was on the Fortune India 500 (as Strides Arcolab) until 2013. Then disaster struck, and it fell off the list; it wasn’t even in the top 1,000 any more. It has now managed to claw its way into The Next 500. I want to ask Kumar about this roller-coaster ride.

Early as it is, Kumar has been here an hour already—he has worked out, showered, changed, and put in some desk time. He says he’s due to talk to his senior management to explain a restructuring exercise. What’s he going to tell them, I ask. What’s his strategy? “Most times, I don’t have a strategy, just a perspective,” he says with a grin.

That, more than anything else he says later, defines Kumar and the way he has run Strides since 1990. It’s always been about doing something slightly unexpected. So, when most other pharma companies were chasing growth in the American markets, Kumar looked to Australia.

Then, he focussed on injectibles, which large players find unattractive. Kumar’s reasoning: It’s better to be a big fish in a small pond. Choosing this business also meant he could ensure stability in pricing, unlike in the large-volume generics market where discounts rule. If that’s not strategy, I need a new dictionary.

More important, Kumar has a track record of selling off parts of the company, acquiring new bits, and generally confounding the market time and time again. Reason enough for investors and analysts to ignore the company so far. Nobody understood Kumar’s business model.

“You got the feeling that Arun was incubating one business after another, rather than focussing on creating a lasting pharma business,” says S.A. Manikandan, who sold his company, Grandix Pharmaceuticals, to Kumar for Rs 100 crore in 2007.

Yes, Strides made injectibles and bulk drugs, but Kumar had other interests as well, notably in startups and real estate. In fact, in 2005, Kumar nearly sold Strides to focus on his other investments. That deal (valued at Rs 400 crore) fell through, and Kumar continued to multi-task.

Then, in 2013, Kumar sold one of the most valuable businesses in the Strides portfolio, Agila, to U.S. generics player Mylan. At $1.6 billion

(Rs 10,107 crore), it was one of the three biggest deals in the Indian pharmaceuticals industry (the others: Ranbaxy sold to Japan’s Daiichi at a valuation of $8.4 billion, and Ajay Piramal’s $3.7 billion sale to Abbott in 2010). Despite having to accept $100 million less thanks to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alert about one of the Agila factories, Kumar managed an above-average valuation.

Flush with funds, the company announced a historic special dividend of Rs 500 a share, setting aside $525 million (pre-tax) for this. News of the dividend sparked a flurry of buying, and once the dividend was paid, those buyers sold the stock. Strides took a beating (see chart below). With Agila gone, revenue fell dramatically, pushing the company off the 500 rankings.

Kumar, who had planned a couple of months’ holiday after the sale, realised he had to get back in the saddle soon. His job: to put Strides back among India’s largest corporations.

His strategy (whatever he’s calling it) is to assemble a bunch of businesses and get all the moving parts to work. Among the bigger buys, less than a year after the Agila sale, was the 2014 acquisition of Chennai-based Shasun (ranked 160 on the 2015 Fortune India The Next 500) for $200 million.

That saw Strides’ market capitalisation rally from $400 million to the current $1.6 billion, bringing back large investors like Singapore’s GIC. Net profit zoomed to Rs 188 crore in March 2016, up from Rs 0.98 crore a year ago. “The investing phase is over,” says Kumar optimistically. “We will now put our heads down and work on integrating all the new businesses.”

Strides entered the Fortune India The Next 500 list in 2016, and could get back on the top 500 this year. Its performance owes much to two events. One, Kumar struck a deal with Pfizer to become a preferred supplier; that’s a $100 million deal. Two, injectible manufacturers in the U.S. were having trouble with the FDA, and several factories were shuttered. In a bid to attract manufacturers, the FDA put injectible product approvals on a fast track. Strides got approvals for nearly 40 products. That wasn’t strategy, says Kumar. “We got lucky.”

Investors are flocking in. Shivanand Mankekar, among the top 10 individual investors in the country, bought a large stake in Strides, as did several foreign investors. Taking advantage of this interest, Kumar sold a profitable Australian business to pare debt. Kumar cashed out despite things looking up. “We knew the capacities that went off production in the U.S. would become compliant and the premium that companies were willing to pay would vanish.”

Kumar is entering territory that will bring Strides into the crosshairs of competitors, which are eyeing niche opportunities. Dr. Reddy’s and Sun Pharma, for instance, want to go after smaller, complex products firms with a sale value of $200 million in the U.S. “Specialty products work as a calling card with big pharmacy chains in the U.S. and so they are worth beyond their sales value,” says a Sun Pharma manager who asked not to be named.

Will Kumar sell? He’s playing his cards close to his chest, only admitting that he has made a number of mistakes in the past. But he has also learnt a lot. “I’m just a little more confident with my bets now.”