India Inc.'s new hotspots for business

Vijay S. Subramaniam, CEO of international operations at Marico Industries, a leading consumer goods manufacturer, says he’s getting used to the sight of empty chairs. He was in Cairo when the mass demonstrations against the government there caused Marico to shut its operations in Egypt for six weeks. The disruption to normal life caused by the protests meant that Marico’s offices in that country were often empty. As head of Marico’s international business, Subramaniam is often in Egypt.

In fact, he’s almost always up in the air—his business card says he’s based in Mumbai, but he’s rarely there. Apart from Egypt, Marico has made strategic acquisitions in Bangladesh, West Asia, North and South Africa, Malaysia, and Vietnam, all of which come under Subramaniam’s watch. Of the Rs 720 crore revenue from its international consumer goods business (which accounts for around 23% of the group’s revenue), at least a third comes from West Asia and North Africa. The temporary shutdown in Egypt resulted in the supply chain being hit for close to two months. Things are still not completely clear. “There’s some uncertainty in the near term,” admits Subramaniam. “But our long-term outlook for the region remains positive.”

Ever since Indian companies ventured abroad, most of the engagement has been with the Anglosphere and Europe—the Tatas’ acqusition of Corus and Jaguar Land Rover, IT companies setting up bases across the U.S., Bharat Forge buying order books in Europe, etc. It’s only in the past few years that there’s been a conscious move in corporate India towards other, less developed but more promising markets in Central and West Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

This marks a significant shift. Indian outfits now have the confidence to do business in nations where often the legal system isn’t fully evolved or language is a barrier. In some ways, Indians represent the sixth wave of globalisers—after Britain and Europe, the U.S., Japan, Korea, and China.

Like Marico, a significant percentage of India Inc. is looking to markets abroad to boost revenue. Companies such as Marico are moving to other countries looking for new markets, while companies such as Coal India, Jindal Steel, Vedanta, and ONGC look abroad for natural resources.

“We have been good managers but have also been risk averse in exploring new markets. This is changing,” says K.T. Chacko, director, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.

Historians talk of the early movement of labour and capital to non-English-speaking, non-Western markets—indentured labour to Mauritius, or South Indian moneylenders in Burma. “India has had a long history of global engagement. Its geographical position placed it at the intersection of major land and sea routes, whether it was the ancient Silk Route, or trading ships following the monsoons both east and west of the Indian Peninsula. Not surprisingly, the average Indian considers engagement with the world a familiar activity,” says Shyam Saran, former foreign secretary, in a paper written for the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization in 2010.

What’s new now is the level of that engagement. India’s outward foreign direct investment in 2010-11 stood at $43.93 billion (Rs 1.94 lakh crore), up from $17.98 billion in 2009-10. The exact amount invested in the emerging markets is not clear; data from the Reserve Bank of India show that investments are often routed through countries such as Mauritius, Singapore, and the Channel Islands. What is clear is that companies are allocating budgets for investment in these markets; Emami has earmarked $331 million for overseas acquisitions, and Dabur has a war-chest of $600 million.

Venturing into new markets is all very well, but the going is not always easy. Some of the problems with the most far-reaching consequences are not work related. Last August, for instance, Godrej had to shut its Nigeria plant and transfer officials because of an alarming rise in the number of abductions there. Frequent travellers like to shock stay-at-home folks with tall tales of cannibalism in Uganda, drug deals going down in Bogotá, Colombia, or violent coups in Southeast Asia. Most company honchos say that these stories should be taken with a large pinch of salt. “In our domestic markets, we have learnt to live with protests, agitation, and violence. We can have Andhra Pradesh erupting one day and Maoist violence the next. If you compare the population affected in one Indian state and in any small country, the situation is not very different,” says Vivek Gambhir, chief strategy officer, Godrej Industries.

Safety is just one aspect. Currency, regulatory, and commodity pricing risks dog companies that want to invest in new lands. But the opportunity in these markets seems to far outweigh the risks. Economists say that several African countries are going through the same economic cycle as India did in the 1980s. In its report Lions on the Move: The Progress and Potential of African Economies, global consultancy firm McKinsey estimates that consumer spending in Africa will nearly double from $860 billion in 2008 to $1.4 trillion by 2020. It adds that industries such as telecom, retail, banking, infrastructure, and agriculture will be worth $2.6 trillion by 2020. By 2040, the African continent will have over 1.1 billion people of working age (between 15 years and 64 years), putting it ahead of China and India. This population can potentially become an engine for global consumption.

Airtel’s entry into Africa has been covered in excruciating detail, but in all the blazing light on that one venture, a host of other smaller forays into the region before and after have gone unnoticed. The Tata group, for instance, operates in 12 African countries through South Africa-based Tata Africa Holdings, in sectors including automobiles, steel and engineering, chemicals, information technology, and hospitality. Srinivasa Addepalli, senior vice president (corporate strategy), Tata Communications, adds that the group also offers fixed-line telephone services in South Africa under the Neotel brand. “Neotel will be an anchor for similar services in other parts of Africa,” he says.

(INR CR)

The other big push for companies entering new markets is the increased awareness of other societies and their needs, thanks to the Internet. For instance, insurance firms don’t want to enter Japan and China, where there’s an ageing population, but are eager to get to African nations, where there’s a booming young population and a growing middle class.

Many of these new destinations have a history of trading with India, and often have a sizeable Indian population. But unlike the past, when Indians were generally involved in high-volume, low-value trade, today’s companies are professional and entrepreneurial, and seek returns. “As investors, we have to evaluate the long-term viability of the business,” says Gambhir. After all, globalisation is no magic wand that ensures returns. The focus today is more on market share than profits. Companies know they have to stay invested for the long term. “When you go into a market, you have to make sure that you are able to support your product for at least the next ten years,” says P.M. Telang, managing director, Tata Motors.

This new wave of globalisation has the blessing of the government, with the Department of Commerce exploring new trade and investment opportunities in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Uruguay, Angola, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Uganda. Jyotiraditya M. Scindia, the minister of state for commerce and industry, has said in several forums that the government is keen on promoting trade relations with African and Latin American countries, and has set up task forces to evaluate the extent of cooperation between India and these countries.

“We are globalising, which is good, but it is also a vote of no trust for the Indian business environment. We are still in the growth phase and a portion of money that should have been deployed in India is also flowing out. These are not good signs,” says a leading banker who has done deals for Indian corporates. Some of his investment banking peers agree; they say that the uncertain regulatory environment, inflation, and high interest rates, and issues of corruption and scams are why companies are looking at markets outside India.

“Indians have held themselves back for a long time. Due to a growing domestic market or lack of confidence or funding, they are now falling to the temptation of acquiring assets outside India,” says Vinay Menon, managing director (equity capital and derivative markets), J.P. Morgan India. Whether it’s a push away from India or a pull to other countries, there’s no denying the new wave of globalisation.

Godrej Industries, a century-old business group, typifies the new thinking in India Inc.—the willingness to go against the grain and take calibrated risks in new markets. In 2005-06, finding its domestic market plateauing, the company came up with a plan to get its products into households across the world. Codenamed Project Leapfrog, the plan spells out Godrej’s intent to acquire consumer goods companies in 20 countries across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. “Our targets are always the top three players in the market. We do not believe in forcing our brand in markets where the acquired brand might have a better foothold,” says Gambhir. The Godrej plan leapfrogs the big markets, such as Russia, Brazil, and Mexico, and instead looks at relatively unknown markets such as Indonesia, Colombia, and Argentina.

Bajaj Auto is another classic case of a company seeking its fortune outside its home country. In the 1980s, fired up by the success of its scooters in India, the company wanted to sell Chetak scooters abroad. Under the terms of the partnership agreement it then had with Italian automaker Piaggio (which manufactures the iconic Vespa scooters), it could not enter Europe. So Bajaj decided to try its luck in the other large market—the U.S. It formed Bajaj America Inc. to sell Chetak scooters in America, but this venture failed. “As sales dwindled, exports fell to as low as 3% of our total revenues. This brought us back to the drawing board,” says S. Ravikumar, senior vice president (business development and assurance), Bajaj Auto.

Today, the Chetak is part of auto history, and Bajaj has moved on from the U.S. failure to successes in Colombia, Central America, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Nigeria, Uganda, and Kenya. In these markets, Bajaj is a leader in motorcycles. It also became the world’s largest exporter of three-wheeled commercial vehicles in 2010-11, according to data from the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers. Of the 3,823,954 Bajaj vehicles sold in fiscal 2010-11, around 35% was exported to 50 countries.

A good chunk of this goes to the sub-Saharan markets, where bikes are used as taxis. This means that wear and tear is high. “Customer service, which this population was not exposed to, helped us gain market share and created the difference,” says Rakesh Sharma, president (international business), Bajaj Auto. He adds that customers there are willing to pay a premium of up to 50% for Bajaj bikes. Sharma and his 70-member team travel across the world looking for new markets and training people to sell Bajaj products. Every year, they train around 4,000 people in Africa. “It is a huge event for them. They welcome our team like we do during marriages, and there are rows of bikes lined up from the outskirts of the cities to the training ground. They celebrate—dance, sing, and treat us like kings,” says Sharma. But Bajaj plans to continue manufacturing the bikes in India, despite the possibility that manufacturing costs might be lower in Africa. “Our Indian capacities are good enough to feed the international markets,” says a Bajaj official.

There is a certain degree of respect for Indians in the emerging markets. The India story is unfolding and they all want to be associated with our growth, values, and our style of doing business,” says Godrej’s Gambhir. His example: Godrej’s acquisition of the PT Megasari Makmur Group in Indonesia. The Indonesian company, which makes household insecticides, wet tissues, and air fresheners, has a strong presence in countries such as Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, and China. The Megasari management preferred Godrej over multinational companies based in the West, as they feared job losses if a Western company took over.

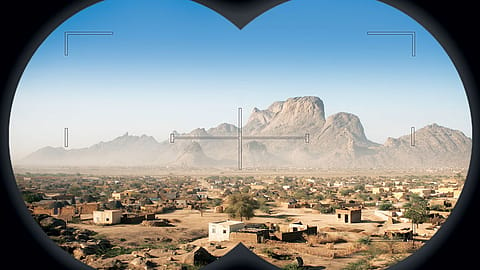

The change is most visible in the Indian presence in Africa. Southeast Asia might be closer home, but it’s the markets in the West Asia-North Africa region (those in trade and diplomatic circles call it the MENA region—Middle East North Africa) that are attracting the most interest now. According to World Bank data, the region comprises 13 countries, with a total population of more than 33.7 crore (337 million), nearly 60% of whom live in urban areas with an average per capita income of $3,229 (Rs 1.43 lakh). Consumer goods manufacturers and IT companies are naturally eager to gain a foothold in this market.

The frontrunners in these new markets are tech companies; many African countries are pushing their e-governance and technology agendas, and, given their experience of implementing such projects in India, Indian IT firms are well positioned to capture this sector. “There is a goodwill rub-off,” says Ameet Nivsarkar, vice president of the Indian IT industry body, the National Association of Software and Services Companies. However, since the deal size of most of these projects is likely to be small, tier I companies are not interested. Nivsarkar agrees. “We have seen smaller companies selecting local partners and signing deals in Africa. There is a mindset issue with the larger companies.”

It’s not that the larger companies are ignoring these markets. Companies such as Infosys, which have a multinational presence, are becoming global recruiters. Local talent and proximity to the North American or European markets make countries such as Egypt, Uruguay, and Colombia attractive for tier I infotech companies. “We have chosen to establish our presence in these locations due to the availability of local talent and language skills. Increasing needs and expectations from clients are also crucial factors,” says S.D. Shibulal, chief operating officer, Infosys.

Meanwhile, smaller companies such as Polaris and Evalueserve have set up development and service centres in Chile and Colombia. “Our analysis shows that the growth rate of the Spanish-speaking markets are higher than the English-speaking ones. Any company looking at a base in the bilingual countries of Latin America will benefit,” says Nivsarkar.

The big question is whether this will result in job losses in India. Nivsarkar doesn’t think so. “The pie is huge and there is lot of potential in non-traditional markets. These new centres will ease the low-end load from Indian centres, which can move up the value chain.”

Of course, cheap hiring is not the only reason for companies to look abroad. As has happened for centuries, companies are going to other countries seeking natural resources. South Africa and some Central Asian countries are rich in these resources, but there’s often the problem of transportation (coal from Mongolia, or oil from Kazakhstan, for instance) and the lack of local infrastructure.

Some companies do manage to get around these problems. In 2004, Lakshmi N. Mittal acquired the South African state-owned steel manufacturer Iscor, which came with mines to feed the plant. In 2006, Apollo bought South Africa-based Dunlop Tyres for $62 million. This gave Apollo access to truck radial tyre technology, which it is now using at its Indian plants for the domestic market. Mahindra & Mahindra’s buyout of Ssangyong Motors in Korea will give it access to the South Korean, Russian, and Central Asian markets.

Other companies are heading to countries that are not necessarily rich in natural resources, but have an abundance of fertile land and low population density. As the pressure on Indian agriculture increases, thanks to the rising population, countries with similar climatic and soil conditions offer outsourcing opportunities.

However, this practice is coming under fire from international nonprofit and advisory bodies such as GRAIN and Food & Water Watch. Desperately seeking funds, the governments of several African countries had allowed international companies to buy vast swathes of land and threw in trade concessions as well.

For instance, Bangalore-based Karuturi Global, one of the world’s biggest exporters of cut flowers, was initially allowed to lease 300,000 hectares of mainly agricultural land in Ethiopia. It also benefited from the government’s liberal terms regarding the remittance of profit and dividends, as well as the fact that roses exported from Ethiopia to the European Union are exempt from taxes otherwise levied on imports.

With international pressure as well as public protests within, the Ethiopian government is now trying to curb the amount of land handed over to foreigners. “There is a certain level of mistrust when it comes to exploiting resources including land. While India’s historical ties with African countries reduce the animosity, it cannot be completely eliminated,” says an official of an Indian company which dropped plans to lease land in Africa, sensing opposition among locals.

Latin American countries could prove a good option, but many of these countries want the Indian government to sign trade treaties before allowing companies access to land and resources. “We want to have better trade in agri products and the food processing industry, timber, fisheries, etc., but India has to reciprocate with a free trade agreement to balance the tax structure,” says Nestor Riveros, Chile’s minister counsellor (commercial). He estimates a 10-fold increase in trade between the countries after the agreement is signed.

No discussion of India’s global trade can be considered complete without mentioning the world’s most populous country. “China is the joker in the business pack. It can score when volumes are required,” says Manoj Pant, professor (Centre for International Trade and Development), Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Other experts say that it’s unfair to compare the two countries; the Chinese government, they say, backs all overseas forays so there is no worry about short-term returns and growth. “Unlike the Chinese, Indian companies will do a lot of commercial viability diligence,” says Pritam Banerjee, head of trade and international policy, Confederation of Indian Industry.

While China might have deep pockets, when it comes to being more easily accepted in a foreign land, it loses out to Indian firms. The Chinese tend to bring their own people into any newly acquired company. Indian companies are generally less threatening. Gambhir says: “Godrej never fires the local team. They know the brand and market better than us. We are acquiring market share, not conquering the market.”