Inner Winner

Page Industries, the company that has the licence to make Jockey innerwear in the subcontinent, is showing bigger companies the way to create shareholder value even without owning a brand.

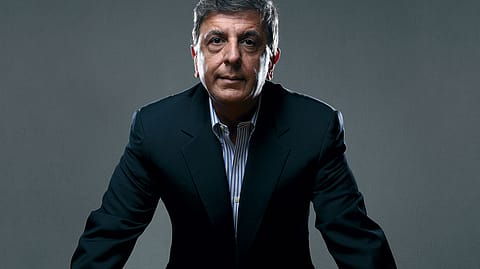

Few people recognise Page Industries, but most know its big brand, Jockey. Page, set up by Philippines-based (now Bangalore-based) Sunder Genomal and his brothers Nari and Ramesh in 1994, is the exclusive licensee of U.S.-based Jockey International for the manufacture and distribution of its branded innerwear and leisurewear in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and the United Arab Emirates. To those who play the market, Page’s claim to fame is not so much Jockey as the fact that its stock has gone up 10 times its purchase price. Page was listed at Rs 341.9 in March 2007 and touched a high of Rs 3,827 in early April this year.

It’s a textbook example of how going premium can work in a company’s favour. Jockey products are priced higher than local brands, and a little less than foreign ones (those that are imported, unlike Jockey, which is made in India). Brokers say the Page stock, like its products, is priced at a premium to its peers. Yet, most brokerages have a “buy” rating on it, based on the fact that Page is growing in volume.

An ICICI Direct research report on Page in February states that “Page has been a fund manager’s favourite owing to its strong fundamentals, healthy growth, and attractive dividend payout.” Though Page has licences to make Jockey products in several countries, it is not able to serve those markets because of the high Indian demand. “When Page witnesses a slowdown in the domestic market, it can always tap international markets. We believe Page Industries is a good play on the Indian consumption story,” adds the report. Other brokerage reports say similar things, and in almost all, Page is a “buy”.

For a company that went public just before the 2008 global meltdown, the consistent upward trend is an achievement. Also, while Page’s share price suffered in the general market instability, there was never an attempt to compromise on products or prices. “When times are a little rough, people become more discerning and buy brands they can trust,” says Genomal, explaining why he didn’t slash prices. And Page made people buy premium brands even during a downturn. Its pricing strategy is simple—around 50% more than Indian brands, but 20% less than international ones. A hosiery retailer in Mumbai’s Crawford Market says this is working. “Customers are happy to shell out Rs 360 for a pack of three [Jockey products], when competing brands sell a pack of two at Rs 160.”

However, not everyone is upbeat about the stock. One stockbroker, who asked not to be named, says he doesn’t like to stay invested in Page and keeps buying and selling the stock because it “tends to remain stagnant and range-bound for long periods, then suddenly has a spike, followed by range-bound trading”. But, he adds, the overall trend remains up, which makes it a short-term buy.

When Genomal, managing director of Page, decided to take the company public, he planned to offer his and his brothers’ shares along with a fresh issue and was hoping to take home Rs 50 crore or Rs 55 crore, depending on the issue pricing. (The shares were priced at Rs 360 and the brothers took home Rs 50 crore.) In addition, Genomal had earmarked Rs 23 crore for brand building and Rs 30 crore for expanding manufacturing capacity.

Page’s IPO was made in the same year as some other big offers, including realty giants DLF and Omaxe, as well as financial services players Edelweiss Capital and Motilal Oswal. When it hit the market, Page was the poorest performer, with no institutional bids on the opening day. By the time the offer closed, the institutional portion was oversubscribed a mere 2.3 times, while the retail side saw lower demand and a subscription of 1.4 times (the number by which demand outstripped the number of shares offered). Compare this with Edelweiss, which was oversubscribed 109 times, or Omaxe (35 times).

One of the reasons for the lukewarm response to Page was that investors were not keen on a company that didn’t own its brand; it was (and continues to be) a licensee of Jockey International, and pays 5% of annual sales as royalty to the U.S.-based company. Also, given that the promoters wanted to take home close to 50% of the proceeds, investors were wary. When the Page IPO opened on Feb. 23, 2007, there were bids for just 3,375 shares against the 28.04 lakh shares that the promoters had intended to sell by Feb. 27, the closing day.

But it looks like Genomal will have the last laugh: DLF, which listed at Rs 525, is now trading at around Rs 240—a loss of over 50%. And Edelweiss and Motilal Oswal have both seen losses of over 90%. Page, meanwhile, has seen its price go up 10 times the purchase price. Because it had a strong international brand and viable plans for growth, investors saw it as a good business—albeit, an expensive buy.

Institutional investors seem to have lost their optimism. Most of those who bought during the IPO or soon after it listed, sold in a few months. HDFC Prudence, a diversified equity fund managed by Prashant Jain, took a 3.03% stake in Page when the company listed. In three quarters, the fund increased its holding to 7%, but by March 2013, it reduced it to 3.5%. Selling earned the fund Rs 140 crore, but had it stayed invested for a month (till April 23), it would have made Rs 190.5 crore. Another HDFC fund (Monthly Income Plan) took a 1.5% stake in June 2007, increased it to 2.5% over the next few years, but by March 2013, had only 1.4% in the company. It’s a similar story with the Kenneth Andrade-managed IDFC Premier Equity Fund, which holds 4.3% of Page as of March 2013, down from 5.4% in 2008. Andrade says the reason he has stayed with Page even through the bad years is that the growth was “beyond our expectations”.

One of the big problems for Page was something it had no control over: the movement of the market. Page, which listed at Rs 341.9 compared to the IPO price of Rs 360, closed at Rs 282—a fall of 17.5%. For the rest of the year, Page traded at an average of Rs 404. By 2008, the general economy was extremely choppy, and this played out in the stock market. By Nov. 20, 2008, its price had fallen 44% to Rs 301.

Despite this, Genomal claims that Page did not really suffer because of the global financial meltdown. “We did not experience any major negative effect on our business,” he says, adding that Page actually averaged growth of 37% over FY08. In fact, he adds, the company did not prune its investment plans—whether it was capacity expansion or marketing spends. “We continued aggressively.”

When it was set up, Page was one of the few players in a largely unorganised sector. It wasn’t that there was no competition; domestic players like Kolkata-based Rupa were already well established and were ramping up. Apparel brands like Zodiac were moving into the innerwear market, and foreign brands were lining up to enter India. And there was the hot domestic favourite—VIP. But Page was on solid ground, since the market for premium innerwear was growing.

Genomal attributes the growth to customer preference. Such demand has led to capacity expansion; back in 2007, Page had envisaged its annual manufacturing capacity increasing to 47 million pieces by March 2008, and 74 million pieces a year later. As of March 2012, Page has an installed capacity of 112 million pieces. When the IPO was launched, men’s wear accounted for 70% of Page’s revenue, and the remaining from women’s wear and leisurewear. Over the past five years or so, this has changed; men’s wear now contributes to 57% of revenue, and the share of women’s wear has gone up.

Equity analyst Sonam Udasi, who heads research at IDBI Capital Market Services, says a strong brand tends to win over investors. “Once a brand is created, it gives you the muscle to deal with customers for the next three or four decades,” he adds. Analysts say this is one of the big reasons for Page’s success. In March 2012, the return on capital employed—which demonstrates a company’s profitability and efficiency—was 54.2%, up from 36.4% in March 2008.

Return on equity has grown similarly—from 32.8% in 2008 to 62% in 2012. As well, its income, operating profit, and net profit, have gone up fourfold over the five-year period. Udasi and his peers say this shows the fundamental stability of the company.

Genomal is, predictably, pleased with such responses from analysts. He adds that several institutional investors have compared Page with Colgate, Titan, and Marico. “Our interactions with investors are always on the business and not market value of our stock,” he says.

R. Muralikrishnan, head of institutional equities at Karvy Stock Broking, expects Page’s top line and earnings to grow at 24% and 26%, respectively, over the next three years. He warns, however, that the stock is not always liquid. But he sees growth, especially “from conversion of the unorganised markets, and from new geographies”.

Page already has a licence to distribute Jockey in other countries in the subcontinent, as well as West Asia. Increased demand could lead to economies of scale, if the company makes India its production hub. “If it is willing to pass on these advantages to the domestic [Indian] market, it would push up volumes further, and hence, increase earnings,” says Muralikrishnan.

It’s not strong demand alone that’s pushing Page up the charts; the company’s distribution and marketing have contributed substantially. “With our strong network of distributors, we are able to effectively reach out widely to our markets pan-India and focus on marketing and brand building on a mass scale,” says Genomal.

A competitor says one of the big reasons for Page’s success is that it spends less than other brands on above-the-line marketing (advertising on traditional mass media, like TV), focussing rather on below-the-line strategies, such as driving sales through promotional offers. Of course, the fact that Jockey is a pretty much universally recognised brand helps, and Page has to do little to advertise the product.

Genomal adds that no matter how strong a brand is, what matters is that the product is good. “We are masters at this,” he adds modestly, referring to his own four decades in the textiles sector, as well as the group’s experience in the field.

The other weapon in Page’s arsenal is its distribution strategy. The company sells through what it calls EBOs or exclusive brand outlets, which are exclusive franchisees across the country. Page has been steadily increasing the number of these outlets, from 30 in 2008 to 85 at the end of 2012. Muralikrishnan believes this strategy helps Page maintain its margins. Large format retail, which is multibrand by nature, is a recipe for brand cannibalisation, since competing brands are placed and sold next to one another. “Being a single brand, Page’s EBOs will never cannibalise its products,” he says.

These outlets help in another aspect as well. As a segment, innerwear is seen as a product that demands privacy, especially in India, and showcasing deters

customers. “Around 30% of customers are hesitant to buy innerwear openly,” says a retailer. The relative privacy of an EBO, where obvious showcasing is unnecessary, helps.

Apart from their need for privacy, Indian consumers generally spend far less than their Asian peers on innerwear. The gap between India and Thailand, China and Malaysia (combined) is a stark 90% plus. But the segment is expected to grow at 13.2% annually, from Rs 14,300 crore in 2011 to Rs 43,700 crore in 2020. With growth in the innerwear market, Page, with a 21% share in the men’s category and 12% in the women’s wear, will benefit. Jockey International seems to recognise that Page will be one of the reasons for it to retain its ‘Superbrand’ status, and declared Page its “Licensee of the Decade”, while extending its licence to 2030.

Page also has an exclusive licensing agreement with Speedo—the world’s largest swimwear brand—to manufacture and distribute Speedo swimwear, apparel, and equipment in India. While Page recorded revenue of Rs 2.8 crore in March 2012 from Speedo, it envisages a 10-fold increase over the next two years, with margins in line with those of Jockey. This latest chapter in the Page story should see even more wealth being created for Genomal and his shareholders.