Consultants don’t add great value: Motherson's Vivek Sehgal

Why Motherson chairman believes customer-driven M&As offer more value that what consultants bring to the table.

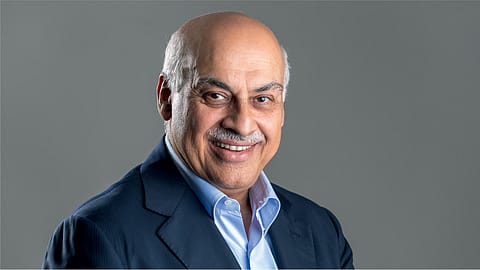

In 2015, Ratan Tata became the first Indian to be inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Nearly a decade later, Vivek Chaand Sehgal, the 67-year-old founder and chairman of the Samvardhana Motherson Group, became the second Indian to join this prestigious club. This year's award is particularly significant, as the forum is also honoring Bill Ford Jr. On the eve of receiving the award, Fortune India caught up with Sehgal to discuss his journey so far and the future that lies ahead for the automotive ancillary major.

What do you consider the most challenging part of being a business owner and a professional manager? How do you separate the roles of owner and manager? Is it an art or a science?

To clarify, Motherson became a public company in 1993. By 1995, I resigned as managing director and brought in a professional for the role when it became evident to me during my frequent trips to Japan back then, that the company performed better in my absence! The ability to distinguish between ownership and management is crucial for any family business. Neither my son Vaman nor I are the president or managing director of any company. We hire professionals and trust them to do the job they’re trained for. When you try to juggle the roles of owner, manager, and professional, it becomes difficult to stay true to any of those roles. We were very clear from the beginning that we would let professionals manage the company.

Motherson has always been in M&A mode, and according to a study by a consultant, companies that focus on smaller, meaningful acquisitions tend to outperform those that go for big-bang M&A deals. Can you break down your thought process?

I have a lot of regard for consultants and meet with them often, but at the end of the day, my team and I have to solve our own problems. When someone from the outside comes in, it's often difficult for them to fully understand the essence of the group, the company, or its people. Consultants tend to follow the more traveled path, which sometimes doesn’t work in acquisition situations. In our case, one plus one doesn’t always equal two; it can equal eleven, or something else entirely.

Similarly, I’m not a big fan of management books. People often give me books to read, and two months later, they’ll ask, "Aap ne padhi? [Did you read it?]" I usually reply, "Haan, woh padi hai! [Yes, it’s lying on the shelf.]" I believe that entrepreneurial thinking—thinking out of the box or lateral thinking—is far more important than simply following what’s already been tried and tested. We’ve done 44 acquisitions, and with God’s grace, they’re all doing well.

Our approach is to solve the customer’s problem by thinking differently. It’s about sitting down, solving the issue piece by piece, and finding the best solution. In all our acquisitions, we’ve never shut down a plant or moved one for labour arbitrage. Many companies, when they buy plants in Europe, immediately move operations to a cheaper country. We’ve never done that. Instead, we solve the problem locally, with the local workforce. This way, the people contribute much more—it’s like giving them a second chance. And we’re quite good at giving second chances.

Recommended Stories

We may not win a Nobel Prize for inventing something, but when a company goes bankrupt, we sit down with the workforce, the customer, and all our teams to find solutions that work.

Can you elaborate?

In 2018, Australia stopped making cars, and we had two plants there. Everyone else had closed their plants and moved on, taking government benefits for retraining the workforce and so on. But we didn’t do that. We kept our two plants running. They are doing very well and making good money. It’s about facing the problem, not taking the easy way out. Some might say, "Let’s take that plant and equipment and move it to India," but that’s nonsense. The customer is still there, and they need a solution. That’s why we don’t strategize in a way that contradicts the customer’s strategy.

Has every single one of your acquisitions—like the 44 — been driven by a problem-solving approach, or has it also been about organic growth? Let’s leave aside your non-automotive ventures for now and just focus on the automotive side — was it always about solving a problem?

(INR CR)

Acquisitions are double-edged knives. An asset might seem cheap, but it can cut both ways. You must involve the three or four main stakeholders to solve the problem—definitely the customer, the workforce, management, and of course, innovation. That’s where the entrepreneur comes in and says, "This is a risk we can take, and I’ll support it 100%." When everyone works together, you find the solution. People often ask, "Why are you successful when others aren’t?" I don’t know why others aren’t, but if you give me the problem, I’ll solve it. You just have to think differently.

It all comes down to the people. It’s not about the machines, topography, or geography—it’s always about the people. If they want a second chance, they’ll take it and give it their best. When a company goes bankrupt, the workforce faces joblessness, and their kids might not go to school or even have food on the table. That’s why giving people a second chance is so important.

We also bring in our bit of know-how and philosophy, like "Full effort, full victory." Once people see that effort, things turn around. For example, in Detroit, we took over a company in 2008-2009. At that time, the Marysville plant was struggling. Today, 15-16 years later, that plant has grown sixfold. The people there are the real protagonists—they built the company, the product, and their own success. Many companies don’t want to manufacture in the U.S. and prefer to move to neighboring countries. I didn’t let that happen. We grew sixfold in the same place.

What about instances where things didn’t work out? How did you handle those?

In our entire history, only one company didn’t perform well, and that was during COVID. The workforce decided to take the government’s offer and close the plant. But its sister plant in India is doing great—the technology and operations are running smoothly. Other than that, all the plants are profitable.

Our approach is not to wake up and decide, "What new field are we entering today?" Most of the time, the customer asks us to explore new ventures, and we say, "Okay, let’s do it." We’re heavily involved in engineering—about 240,000 people work for us globally, and around 30% of them are engineers. It’s a massive, heavy engineering operation. But there are no wild dreams—if you ask me, "What are you planning for tomorrow?" I’ll tell you, "Nothing, I’m happy as things are."

One thing that’s consistent in all our acquisitions is that they are always customer-nominated. We don’t wake up one day and decide, "I’m going to buy this company and be number one in the world." That kind of thinking is for tombstones, right? "From this year to this year, he was number one, and now he’s six feet under." Instead, if a customer sees value, they ask us to step in.

People often ask, "What are you doing for EV? Batteries? What’s the plan?" I tell them, "No customer has asked me to look into a battery maker or EV car part maker." While the world seems to be moving towards EVs, we haven’t pursued it yet because our customers weren’t asking for it.

Everyone in India is talking about EVs, but the story seems different in developed markets like the U.S. and Europe. How are you navigating this period of uncertainty?

We don’t tell the customer or the vehicle maker what to do—they have their own strategies, likes, and dislikes. But there’s enough room in the automotive space for us to play the role of problem-solver. We have almost 30 plants in China, but I didn’t go there—the company did. We’re solving the problems where they are. The world is so diverse that it’s hard to find one solution that fits all. We follow a simple rule called "3 C x 10," which means no country, no company, no component should account for more than 10% of our turnover. But if an opportunity comes along where that’s exceeded, we wouldn’t say no—we just make sure other divisions contribute too.

In the next five years, will non-automotive become more central to your business?

We don’t ask: "Is this the right thing?" or "Is that the right thing?" Motherson takes a project, whether it’s in its seed form or a massive built-up plant, and we develop it. I focus on what the customer wants and what my people can achieve. If we can maintain the standards the customer expects, we’re good to go.

How are you managing analyst expectations?

I don’t bother too much about what the market is thinking. The fact is that from 1993 to date, we have grown the company’s top line by 35% every year, and every year we have returned 32% to shareholders. Show me another company that has done that consistently. If you had invested ₹25,000 for 1,000 shares in 1993, today that investment would be worth ₹11 crores.

So, what was the trigger for the QIP?

We did it essentially because we don’t like to be in debt [Rs 10,372 crore as of March 2024]. Over the next six months, something important [M&A] may come up. So, we are just keeping some firepower ready —about ₹7,000 crores or so. If nothing comes up, we’ll reduce our debt. Either way, it’s a win-win.