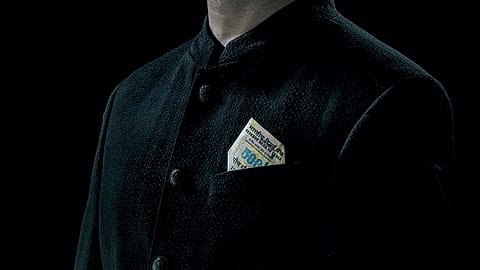

Foreign policy means business

Indian Prime Ministers have tried to put economics at the heart of foreign policy . But none has made it as personal a mission as Narendra Modi.

R.C. Bhargava is a veteran of travelling with Indian Prime Ministers. For nearly two decades, the Maruti chairman has been listening to Indian prime ministers on foreign tours tell the world about the lure of India: a massive market, young workforce, and a growing economy. But, he says, “beyond the hype, which is cyclical, was the reality of India, where doing business was often very difficult”. India’s consistent low rank in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business index also sieved PR from reality.

And then, Bhargava travelled with Narendra Modi to Japan last year. “He said ‘We know that businesspeople face a lot of problems. We are committed to solving those problems. I am personally responsible for solving those problems’,” says Bhargava. “The big difference is that no Prime Minister before Modi took personal responsibility to fix things on the ground. It was always about population size, youth, none of which they had any role in. But Modi is far more realistic. He knows that just because there is a big market does not mean business can happen there.”

It seems a bit of a dramatic conversion, but the fact is that for Bhargava and his peers, this is one of the big differentiators of the BJP-led government—how Modi is trying to redefine foreign policy. At its core, it’s about bringing some realism to the rhetoric. For instance, since 2006 there has been a person in the Prime Minister’s Office to help with Japanese investments. Modi has transformed this into a Japanese cell, which will include two nominees from Japan. The idea is that the Japanese will know exactly what their companies need. There’s a similar provision made for American investors, where a senior joint secretary will head a small team to focus on investors from the U.S. (So far, there have been no announcements about whether similar teams will be set up for other countries.)

IT'S NOT A NEW idea by any stretch; India has been trying to put business first in its diplomacy for many years. Rajiv Gandhi was the first to introduce some business-friendly measures to foreign policy, including making the Prime Minister’s office responsible for helping foreign investors. Shashi Tharoor, former minister of state for external affairs in the Congress Party-led government of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, says Singh set the ball rolling by ensuring that all embassies got the message that they had to be “aggressive centres of propagating trade”.

But in spite of the past push, there is a perceptible difference in the Modi way as seen from his visits from Japan to Australia. The think tank Carnegie Endowment for Global Peace says “geoeconomics” (also known as neomercantilism, where the government pushes for greater exports than imports) is the guiding force in India’s foreign policy under Modi.

What Modi is doing, says Tharoor, is “adding rhetorical prominence to economic diplomacy”.

The renewed economic push stems from a couple of factors. One, it’s important to remember that Modi’s key constituency has always been the business community; previous (non-BJP) governments had a socialist bias, at least on paper. Kanwal Sibal, former foreign secretary of India, explains. With Prime Minister Singh, he says, the government was impeded even in its first term by the creation of the National Advisory Council, a pressure group of Left-leaning activists headed by Congress Party president Sonia Gandhi, Singh’s boss within the party. Modi has no such shackles, and as a result, says Sibal: “We are no longer afraid to break the rules.”

Two, Modi is reinventing himself from the successful chief minister of a state to a world leader. And in this effort, says Sibal, he’s taking the pitch that “India has the power to deliver”, rather than “India seeking assistance”, which is the line Manmohan Singh and his predecessors used. (Interestingly, it is at this time that after spending most of its independent history as a net recepient of aid, India is now a net donor.) This is something that has struck foreign policy expert Richard M. Rossow, senior fellow and Wadhwani chair of U.S.-India policy studies at the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies. “The BJP government is not guided by India’s traditional policy of non-alignment,” Rossow says. He adds that the election of a business-friendly government is a positive for the country.

Veteran Indian bureaucrat N.K. Singh tells me an anecdote when asked what he thinks of Modi’s attempts to marry foreign policy with business. (Disclosure: Singh joined the BJP from the Janata Dal a few months ago.) Singh was at a dinner at Tokyo’s Akasaka Palace, hosted by the Japanese government to welcome Modi during his first visit to a major foreign country after taking over. He met Osamu Suzuki, the 84-year-old chairman of Suzuki Motor, and Suzuki seemed enthusiastic about Modi’s victory. Maruti Suzuki had been in India for decades, and owed much of its initial success to the Congress government of the day, so Singh asked him about this new enthusiasm. “The [Maruti Suzuki] factory in Gujarat will be the fastest installation of any of our factories anywhere in the world—and I can drink beer in it!” explained Suzuki. This was a special permit that the Gujarat government (which has, otherwise, imposed full prohibition in the state) occasionally hands out, and when Modi was chief minister, he had given one to Suzuki.

No law was broken, but the impression Suzuki got was that he and his company were welcome in the state. And that’s the kind of welcome he expects from Modi now that he’s Prime Minister. Sibal adds some perspective; the message that Modi is sending out, he says, is that “we will work with anyone who serves India’s interests”.

MODI'S PUSH FOR a more open, business-friendly India comes at a time when the U.S. (and American companies) faces difficult times in doing business in two of the largest countries in the world, Russia and China. From Congo to Iran and Pakistan-Bangladesh, the conflict zones of the Cold War are aflame. In October, at the resort town of Sochi on the Black Sea coast, Vladimir Putin gave his fiercest speech against the U.S., blaming American foreign policy for everything from jihadi terrorism to a new arms race. In China, even before the latest clashes over pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, scores of Fortune 500 companies, from Apple to Volkswagen, have faced the wrath of Chinese investigators—from fines for price fixing to security investigations, including the location tracking technology of the new iPhone.

Squeezed in two large markets, and with both the Brazilian and South African economies in what seems like endless stagnation, India offers rare hope to U.S. companies. Arvind Virmani, former chief economic advisor to the government of India, says: “The U.S. capital market is clearly showing interest, but U.S. business will show recognition only after there is clear evidence of investment and growth revival in India, probably by Q1 (first quarter) of 2015.”

Virmani adds that improved Indo-U.S. relations could be the one area of foreign policy where U.S. President Barack Obama “can still leave a positive mark”. He adds that improved trade relations, especially in sectors such as defence, “will certainly be an important factor in the relationship as India regains its position as one of five fastest-growing economies.” This, perhaps, was one of the reasons for the bonhomie that was so much in evidence when Obama came to India on Modi’s (tweeted) invitation. Among the several initiatives, amounting to $4 billion (Rs 25,268 crore), announced as a result of the visit, was a new Indian Diaspora Investment Initiative, $2 billion in leveraged financing for renewable energy investments in India through the U.S. Trade & Development Agency, and $1 billion in loans for small and medium businesses.

On his part, Modi has been pushing India’s business agenda in the U.S. Never overtly stated is the fact that improved Indo-U.S. trade ties could help both countries deal with China in their own way. In recent years, India has had to try harder to compete against China in the global hunt for energy resources, especially in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa. “The Chinese have always worked with the government at the forefront and then the companies bringing in almost everything from China including sometimes even press-ganged prison labour,” says Tharoor.

So far, there has been no concerted state push to encourage business abroad, preferring soft power when dealing with other countries. “The Indian government and Indian companies have been far more engaging with the local population,” explains Tharoor.

Mini vandePol, veteran India hand at Baker & McKenzie, the world’s largest law firm, doesn’t think soft power through corporate India will be enough if India is to truly make a mark. She is working in India auditing and conducting a forensic investigation on three Fortune 500 companies (she won’t name them) which are being investigated by the U.S. government for improper business practices. (Rampant corruption and a series of scams during the earlier government have dented India’s capability to pitch economics on the world stage.)

vandePol says China has been demonstrating more determination to stamp out corruption than India. “What business wants is security and if India wants greater trade to be the cornerstone of its foreign policy, then that sense of security will only come if laws are applied without fear or favour,” she says. “The fact that China is doing more at the moment to solve corruption is a problem for India since it is a competing market.”

The big problem is that India has entered this contest way too late, and simply cannot compete with China on trade and business grounds. Even if the government supports companies going abroad and demands a furtherance of the state’s agenda in return, in sheer scale, the Chinese win. That’s why Modi’s efforts to woo China’s historical competitors (the U.S., Japan) make sense. It’s also why India is seeking to have a greater say in matters of strategic importance in the region. (The country was recently admitted as a member of APEC, or the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, an international body of 21 countries including the U.S. and Japan, which promotes free trade among its members. Both the U.S. and China have welcomed this.)

There are detractors, of course, who believe that Modi’s efforts could lead to India becoming a pawn in a bigger game. In a recent column, Mani Shankar Aiyar, a Congress member of the Rajya Sabha, wrote: “During Cold War I between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. in the 20th century, the U.S. co-opted Pakistan as its ‘most reliable ally’. With the onset of Cold War II in the 21st century, now between the U.S. and China, Barack Obama made his Republic Day visit to India to woo Narendra Modi to become the U.S.’s most reliable ally.”

This is the kind of knee-jerk reaction that Rossow warns against. At a presentation before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Near Eastern and South and Central Asian Affairs, he said that looking at the Modi government through past lenses would be flawed. “My fear is that we will approach the Modi government with the same agenda we used in recent years. We need to recognise the Modi government’s priorities, and where these priorities intersect with our own. This middle ground must become our shared agenda.”

SOME OF THE GOVERNMENT'S focus on the business of trade also comes from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological parent of the BJP. It slipped past most economic analysts that one of the big things that the RSS chose to celebrate this year was the 1000th anniversary of the coronation of King Rajendra I of the Chola dynasty who ruled between 1012 and 1044 CE and expanded the maritime trade prowess of the southern Chola empire across Southeast Asia, making the Cholas one of the great trading powers of Asia at that time. The RSS is focussing attention on the trading prowess of India in its so-called “golden age”, a time when Roman intellectual Pliny The Elder was complaining (in 77 CE) that the empire’s lust for India’s precious stones and silks were emptying the coffers.

It may take more than a Prime Minister getting gung-ho about foreign trade to bring that golden age back. There are way too many problems in the current system for that to happen. Bruce Hambrett, another India hand at Baker & McKenzie, points to one of the major problems: more than 30 million cases pending at various courts. He says other countries in the region, from Japan to Malaysia, are working to ensure that corporate cases can be resolved in record time. Singapore has separate commercial courts; Australia has special judges to resolve big-ticket transnational corporate disputes. “Unless an efficient system of resolution is created, no amount of global pitching will convince companies.”

That’s why both vandePol and Hambrett cheer Modi’s push for greater e-clearances for licences—which could even be 100 in some industries—for setting up businesses. “Some people are asking if it’s band-aid, and it definitely is not. It is important for our clients to know that the processes are online. It helps push the idea of transparency,” says vandePol. Now to pitch this around the world.