The big Indo-U.S. tax conundrum

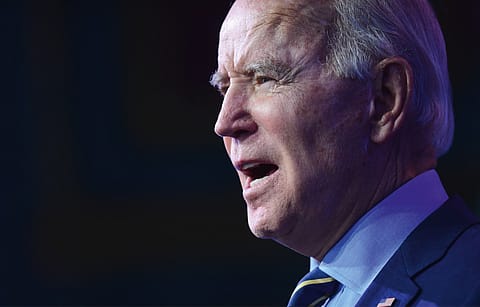

India has much to gain if U.S. President Joe Biden focusses more on expanding bilateral free trade and investment, rather than go ahead with his tax proposals. But it won’t be easy.

The row over the recent U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) probe report that flagged India’s digital services tax, the Equalisation Levy, as being “inconsistent” with U.S. trade policies, may well test the tone of the new administration under President Joe Biden on tax issues facing Indo-U.S. businesses. U.S. lawmakers, irrespective of their political affiliations, have been known to be touchy about taxing of American digital businesses.

What is also keeping many Indian and American businesses on tenterhooks are the new administration’s poll campaign proposals to raise corporate taxes and measures to discourage offshoring and encourage onshoring of U.S. goods and services. With the Democrats enjoying a majority in the Congress, the Biden administration gets more leeway to implement its tax proposals.

“It will be busy times for U.S. taxpayers and their advisors,” says Dinesh Kanabar, CEO, Dhruva Advisors, a tax advisory firm. If Biden goes ahead and implements all his poll proposals, it might mean a rollback to a regime of higher rates. Former President Donald Trump, through the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, brought down the federal corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, the lowest in decades. This was in line with the Republican poll promise of attracting investments into the country by making the U.S. among the lowest tax jurisdictions in the world.

Mukesh Butani, founder and managing partner, BMR Legal, points out that while ushering in the new tax regime, many Democrats had agreed with the Republicans that the 35% rate hampered the competitiveness of U.S. firms in an era in which various countries, including India, had slashed the rates of corporate tax.

Tax experts say some components of the existing framework will likely continue under Biden. That means some degree of uncertainty in the tax regime—something most businesses dislike. The requirement for U.S. multinationals to remit overseas profits into the U.S. (or pay taxes on them) might continue, says Kanabar. A higher tax rate will mean increase in tax liability for U.S. companies, impacting the amount of foreign tax credit they enjoy. (U.S. multinationals are entitled to a tax break from the government in the form of foreign tax credit based on the amount of tax they pay on their foreign investment income to a foreign government.) Kanabar points out that companies would need to re-configure the cumulative tax cost in India, and the ability to set it off against the U.S. tax liability on consolidation.

Some tax experts feel that with the U.S. economy still running below its full capacity, increasing taxes out of the gate is a decidedly suboptimal path that Biden may not adopt anytime soon. “While taxes will certainly rise, what remains uncertain is whether those increases will be phased in, or what any prospective tax reform will look like,” says Mukesh Patel, senior director, international tax services, and India desk leader, RSM US.

The corporate tax rate is not the only factor that will influence businesses. “We need to wait and see how the proposals that Biden announced, particularly with regard to a plan to impose new business taxes designed to discourage offshoring of U.S. manufacturing, is viewed,” says Butani.

More Stories from this Issue

Some experts find Biden’s proposal on offshoring penalties a bit dated. Based on a 50-year-old doctrine of capital export neutrality (CEN), experts say it envisions a U.S.-based multinational paying the same tax rate on profits earned abroad (after combining foreign and U.S. taxes), as on profits earned at home. However, over the years, most countries abandoned this concept, including the U.S. in 2017. CEN also does not address border-agnostic digital businesses, says Butani.

One of Biden’s biggest challenges will be to flesh out the U.S. stand on the OECD’s efforts to arrive at a common global framework for taxing digital transactions. That would also be of interest to Indian policymakers given the recent U.S. proposal to retaliate against India for imposing the Equalisation Levy. On its part, the Trump administration did not participate much in the OECD deliberations, while it strongly defended the U.S. tax base for these digital companies.

Tax experts say some components of the existing framework will likely continue under Biden. That means some degree of uncertainty in the tax regime—something most businesses dislike. The requirement for U.S. multinationals to remit overseas profits into the U.S. (or pay taxes on them) might continue, says Kanabar. A higher tax rate will mean increase in tax liability for U.S. companies, impacting the amount of foreign tax credit they enjoy. (U.S. multinationals are entitled to a tax break from the government in the form of foreign tax credit based on the amount of tax they pay on their foreign investment income to a foreign government.) Kanabar points out that companies would need to re-configure the cumulative tax cost in India, and the ability to set it off against the U.S. tax liability on consolidation.

Most tax experts do not anticipate a significant change in the U.S. stand. However, as Patel puts it, the U.S. is bound to realise that it needs to engage in a negotiated resolution to the taxation of digital commerce. That said, Biden might not have much time. The OECD has a mid-2021 deadline to arrive at a broad political consensus on the global tax framework. “Reaching a consensus by mid-2021 will require early U.S. engagement,” says Grace Perez-Navarro, deputy director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration. Still, the OECD is cautiously optimistic. “We do not expect to see a fundamental shift in the U.S. position given the bipartisan statements that have been made on this issue in the past. Perhaps with a new set of eyes looking at these issues, and a strong desire to avoid tax and trade wars, a consensus-based compromise can be found,” she adds.

OECD officials and tax experts point out that many digital businesses have benefitted and grown as a result of the pandemic. This increases the pressure on governments to address the tax challenges arising from rapid digitalisation of the global economy. Perez-Navvaro says unilateral solutions carry great risks in terms of trade sanctions, double taxation, and increased tax uncertainty at a time when the global economy can ill afford such consequences.

(INR CR)

To an extent, the Biden administration’s trade policy would have a direct bearing on many tax-related issues, feel experts. Most expect him to adopt a more measured approach, and negotiate agreements that encourage bilateral free trade and investment. The uncertainty in the tax regime may remain for some time, but for Indian and U.S. corporations, the prospect of more business coming their way is helping them stay optimistic.

(The story first appeared in Fortune India's February 2021 issue).