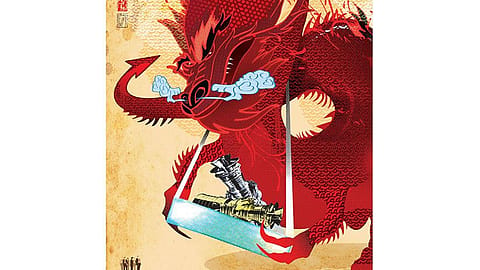

Tripping on Chinese power

As Chinese power equipment flood the market, local players urge buyers to look beyond the price tag. But nobody’s in the mood to listen.

When it comes to competing with the Chinese, Indian power equipment manufacturers complain that they are at a disadvantage even on home ground. Companies such as L&T Power and Bharat Heavy Electricals (BHEL) say their Chinese competitors have several advantages over domestic firms. For one, while Indian players are denied access to the Chinese equipment markets, Chinese players have a free run here because there is no import duty on equipment for mega power projects (4,000 MW and above) undertaken by the private sector.

Also, the Chinese government gives power equipment manufacturers a subsidy. Add to this an undervalued currency, and it’s easy to see why it’s advantage China.

Domestic players say the majority of private power producers in India prefer to buy Chinese equipment because it works out far cheaper than anything made in India. What also tips the scales in favour of Chinese players is the easy financing available from Chinese banks at very low interest rates, especially from their Export-Import Bank for financing equipment. “Today, if an Indian power producer has to take a loan to buy equipment from any domestic player, it will have to pay an interest of 13% to 14%, compared to 4% from the Chinese Exim Bank,” says Ashok Puri, CEO of Hinduja National Power Corporation. That can make a huge difference in decision making.

Take Reliance Power’s deal with Shanghai Electric, for instance. The Indian company has already been assured of a $12 billion (Rs 58,344 crore) flexible long-term loan from the Chinese Exim Bank at a low rate of interest to finance 36 plants of 600 MW each. “With the financing tied up, we can now confidently go about our business,” says a Reliance Power official.

ALL THIS RESULTS IN the Chinese having an unfair advantage in India. Even as the Indians lobby the government to create a level playing field where Indian and Chinese products can fight on their own merits, they are first trying to get domestic financiers on their side.

In September, Ravi Uppal, president of L&T Power, met a number of bankers and financiers, including Zarine Daruwala, president, ICICI Bank, S. Vishvanathan, managing director and CEO, SBI Capital Markets, and Rajiv Nayar, MD, Citibank. For close to an hour, Uppal spoke about the dangers of funding power projects based purely on a rupee-per-MW basis, where a project that produced 1 MW of power at a lower cost had easier access to funding.

“On the face of it, plants based on Chinese technology may appear attractive because of lower costs,” he said. “But over its life cycle, when higher running costs and performance issues kick in, they might prove to be a huge drain on resources and far more expensive.”

Uppal was referring specifically to the sale of boilers, turbines, and generators, all of which L&T makes. Chinese firms—led by Shanghai Electric Corporation (SEC), Dongfang Electric Corporation (DEC), Shandong Electric Power Corporation, and Harbin Power Plant Electric Corporation—have sold more than Rs 1 lakh crore of equipment to private Indian power producers in the past five years.

“We would not be surprised to see Chinese equipment makers take up to 30% market share in India in the long run,” says a Credit Suisse research report released in January. In 2010, the top three Chinese power equipment makers had several high-profile wins over their Indian counterparts. The Indians, seeing such large orders slipping from their grasp, insist that private players are not getting the best deal by opting for low-cost equipment. A recent study by Bank of America Merrill Lynch shows the advantage of taking the total life cycle cost into consideration. In a typical case (a supercritical project of 600 MW for around Rs 1,300 crore), a Chinese company charged Rs 1.6 crore per MW—30% less than BHEL’s price. (BHEL is India’s largest power equipment manufacturer). However, when life cycle costs (the total life of a plant, which is generally between 25 years and 35 years) are compared, the Chinese price of Rs 2.47 crore per MW is almost in line with the Rs 2.6 crore per MW that BHEL charges.

The higher life cycle cost for Chinese equipment is because of higher auxiliary power consumption—the total power required to run the plant including workstations, lighting, air conditioning, etc. In the supercritical category, the auxiliary power consumption of Chinese equipment is 6.5% compared with 4.9% for BHEL. The Indian company’s plants are more efficient, with a plant load factor (PLF) of 85% to 95%, which is at least 5% to 10% higher than its Chinese counterparts.

HOWEVER, THE PRICE DIFFERENCE is steep enough to take care of higher running costs. When Credit Suisse used Shanghai Electric’s contract with Reliance Power as a benchmark—an $8.3 billion deal—to study the pricing disparity between Indian and Chinese players, it found that the difference was over 50%. SEC’s pricing worked out to be Rs 1.5 crore per MW against BHEL’s Rs 3 crore to Rs 3.5 crore per MW for the boiler-turbine-generator set, as well as other components, and setting up the power plant. Even assuming that auxiliary costs are a good 3% to 5% more than BHEL, the basic price difference is steep enough to take care of this.

(INR CR)

Added to the easy financing and cheaper equipment is the Chinese vendors’ ability to meet deadlines. A Chinese equipment provider typically takes up to 36 months to deliver, compared to 48 months for an Indian vendor. That’s because Chinese companies have a huge manufacturing capacity—3,409.2 MW per year for Shanghai Electric vs. 15,000 MW for BHEL and 6,000 MW for L&T. “What that means is that companies can begin production much faster and start earning much faster if they use Chinese equipment,” adds the Reliance Power official.

There are some private players who still prefer to buy Indian. When Videocon Power called for bids for setting up two 600 MW power plants in Pipavav, Gujarat, the Chinese bids were 15% lower, remembers V.K. Ahluwalia, then CEO and now advisor to Videocon Power. However, the company realised that Chinese equipment was not made to suit Indian conditions and local raw materials; if it had to be used in India, it needed to be customised, adding to the cost and delivery time. The Rs 5,500 crore contract went to BHEL.

Hinduja Power, too, has stayed away from Chinese vendors for similar reasons. “All power equipment in this country must be customised to the prevailing soil, coal, and ambient conditions. Standardised and mass-developed equipment, such as those produced by the Chinese vendors, will not work,” says Puri of Hinduja Power.

Indian coal has a high ash and moisture content, large amounts of noncoal matter, and a low calorific value, so equipment vendors will have to manufacture differently designed turbines and other components. “The quality of the coal deteriorates as it is mined further and further, thereby making the task of designing the boiler that much more difficult,” adds Puri. BHEL, which Puri headed for five years, specialises in making customised equipment, and offers a guarantee to provide spares and maintenance during the life cycle of the plant.

Chinese vendors are generally unable to offer similar guarantees. Uppal offered one of these reasons to the financiers at the Mumbai meeting: Chinese companies sell only their in-house designs, which are copied from international ones.

He said if SEC, DEC, Shandong Electric Power, and Harbin Power were to provide world-class equipment such as those designed by Mitsubishi (Japan), Siemens (Germany), ABB (Switzerland), or Alstom (France), the cost would go up exponentially. But the Chinese are not allowed to sell other designs, even if they have an existing joint venture with an international manufacturer.

The other reason that Chinese firms cannot offer replacement and maintenance guarantees is because they don’t have factories in India. If there’s a problem, the equipment is shipped back to China and repaired there. That’s what happened at Durgapur Projects’ 300 MW plant, which had been bought from Dongfang Electric. After 18 months of operation, the plant failed in February this year, and the equipment was sent back to China. The plant had to be shut down for 81 days, leading to huge revenue and production losses.

Something similar happened in West Bengal Power Development Corporation’s 300 MW Sagardighi project, where the turbine blades collapsed in May last year. The plant was out of action for a whole year. Sterlite, too, faced similar problems and delays. While the power regulator, the Central Electricity Authority, has asked foreign power equipment manufacturers to set up factories in India, it’s too early to say if this will happen or if it will help.