Carnival Cinemas: How to ace the great Indian screen test

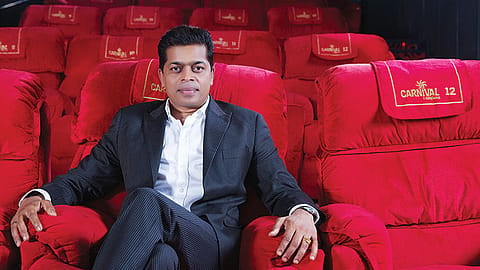

Shrikant Bhasi talks about how he made Carnival Cinemas India’s third-largest multiplex chain.

With three major acquisitions in a little over six months, relative upstart Carnival Cinemas has raced to a tally of 346 screens, behind only PVR and Inox. Owner Shrikant Bhasi, former Britannia executive-turned-agri-trader-turned exhibitor, tells his story.

I hail from Angamaly, a small town in Kerala’s Ernakulam district, but grew up in Bhopal where my father worked for Bharat Heavy Electricals. I have no family background in business. After graduating in 1987, I joined Britannia Industries as a summer trainee, was taken on as a regular employee, and stayed for five years working for its agriculture division. In those days, Britannia’s products included a brand of soyabean oil called Vital. The division included a crushing plant where soyabean seeds were crushed to produce oil.

I saw a lot of potential in the cooking oil business. So in 1992, my boss Ravi Nigam and I quit the company and turned entrepreneurs. We took a crushing unit in Mumbai on lease where we crushed and processed seeds for different companies. This was good for three years, but then the government policy changed and it was no longer profitable. Next, I got into the rice business as PepsiCo’s sole agent for selling basmati rice. Later, I also procured potatoes for it, among other things.

I always had the urge to do something new and different, and saw an opportunity in the film industry. In those days, structured finance—working out customised financial products for companies to enable them to raise funds from financial institutions—was not common. There was a good potential for structured finance in Bollywood. In Hollywood, most movies are funded through structured finance, but not in India, where film financing is largely unorganised. I thought we could bring in structured financing and get into the completion bond business, where a studio enters into an agreement with a producer to ensure that the film is completed even if financial problems arise.

I talked to a few people but found them uncooperative. I thought of making films myself using structured finance, but a mainstream Hindi film cost Rs 20 crore to Rs 30 crore and I couldn’t raise that kind of money. So I decided to experiment with a Malayalam film. I got a script and gave it to leading director Sibi Malayil, which eventually became the movie Violin. We did a completion bond and tied up with a distributor. The estimated budget was Rs 1.5 crore, but the actual expenditure shot up to Rs 3.5 crore. I thought the movie would release in 80-100 theatres and I could recover the money quickly. But the distributor said I would not get more than 35 screens, because there were just not enough screens. There were only two multiplexes in all Kerala.

That set me thinking. China has 26,000 screens for a population of 1.5 billion people. In comparison, India, with a population of over 1.2 billion, has only about 6,000 screens, 1,700 of them multiplex screens. We produce more movies than China. There is clearly a gap between supply and demand, and the gap will remain for at least 15 years. So, I thought, why don’t I get into building multiplexes?

I opened my first multiplex in Angamaly. Bankers thought I was mad. “Who will pay Rs 80 for a ticket in Angamaly?” they said. But I knew people spent Rs 50 to Rs 60 on petrol going from Angamaly to the nearest big town, which had proper theatres. They were paying Rs 100 for a ticket.

The multiplex was an instant success. The benchmark occupancy for theatres is 20% to 25%, but in the first week, ours touched 80%, and today the average is 60%. That is because there is no other multiplex in the area. Secondly, in Kerala, most families never went out to movies together because there is no proper security, there are no proper facilities. I focussed on strict discipline and maintenance to attract families. Today, I have families coming for the 11 p.m. show without any problem.

Subsequently, I felt I needed a pan-India presence. I saw HDIL’s Broadway Cinema chain with 10 theatres, including those in Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, and Indore. Last July, we acquired the company and started renovation.

The next acquisition was the big one—Reliance MediaWorks’ Big Cinemas with 254 screens. There were other bidders, including funds based in the U.S. and Singapore. I spoke to auditors KPMG and they fixed up a meeting with Anil Ambani. I made a full presentation. I showed how Big Cinemas could earn 3% to 4% more than the industry’s benchmark Ebitda. Right now the benchmark is about 15%, but I’m hoping for 18% to 20%. Ambani was very impressed. He also told me he likes to support first-generation entrepreneurs and decided to sell to us. The deal size was about Rs 700 crore.

The last acquisition was Glitz Cinemas, with 27 screens, which I chose because it was very strong in Chhattisgarh, where Carnival had no presence.

(INR CR)

I don’t really like inorganic growth, but it had to be done to get scale within a short time. Consolidation is the name of the game. You cannot achieve much with 20-30 screens. Our acquisitions are funded by both internal accruals and private equity. Internal accruals will gradually be replaced by PE funding entirely, both debt and equity. I’ve made a promoter’s contribution. If you see the acquisitions, they are not only in metros. I’m also building multiplexes in Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh. Ideally, we should take four years to five years to recover capital costs.

When you get into a business, it is important to know every aspect of it. So we have produced four Malayalam movies and one Bollywood movie. But I’m very clear I’m not a creative person and will never get into the creative side of the business. I’m a businessman.

Over time, I have also got into food courts and restaurants. We have strategic investment in an IT park in Kochi and have just taken over another in Thiruvananthapuram. Talks are on to acquire a mall in Chandigarh.

When we started, we had a goal which we called “Vision 300”—300 screens. That has been achieved. Our new goal is “Vision 1,000”—1,000 screens by the end of 2016.