Making sense of Rahul's economics

And what it could possibly mean for business.

RURAL MAHARASHTRA. An urbane, 40-something politician, dressed in white khadi, is addressing hundreds of Bhils, out in all their finery. “We know, and you know, that the forests were not spoiled for thousands of years. The tribals have never damaged the forests. Sometimes outsiders have misguided the tribals for their own benefit and oppressed them. Our effort is to rectify these wrongs.”

Cut to eastern Orissa. An urbane, 40-something politician, dressed in white khadi, is addressing hundreds of Dongaria Kondhs, who are out in all their finery. “This is your hill. It is sacred to you. You have protected your hill. Some people said this is against development. This is not true. There is no development without the voice of the poor.”

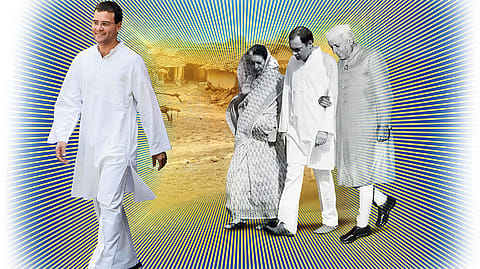

The message is similar, as are the clothes, and the easy charm. This is India’s ‘back to the future’ moment—spanning a generation. Championing the Bhils was former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, in 1989. Twenty-one years later, with the Kondhs, it is son Rahul, general secretary of the All India Congress Committee.

When Rajiv Gandhi was in Maharashtra, speaking in support of the Bhils, he was fighting for his party’s victory in the 1989 elections. (The Congress lost. Two years later, campaigning again, he was assassinated.) Much has changed since: India no longer sees ‘free market’ as a taboo phrase, and is no longer content to live in her villages. Today’s India has ambitions of being a world power, and has no reservations about making those ambitions clear in global forums. And politics now is mostly economics.

After avoiding the limelight for most of his adult life, Rahul Gandhi, 40, has been very visible in the last three years. Besides Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and mother and Congress party president Sonia, Gandhi is the most important person in the ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition. Many believe he will be the next PM if the UPA wins the 2014 elections.

So far, he hasn’t announced any economic manifesto though he is increasingly wading into different economic debates—land acquisition, jobs, grassroots development, etc. For a country that seeks fulfilment through GDP growth, his overall economic thinking is still a bit of a mystery. And a topic that corner offices across India Inc. are trying to understand. Is he for big government or small? Public sector or disinvestment? How much state intervention does he think is necessary? Is he Left-leaning or Right? What does he think of the role of business? Will natural resources be leased or sold?

Gandhi is no trained economist, and, as critics point out, he has had long gaps between jobs (the usual comparison is with his father, who gave up his career as a pilot to enter politics). It all comes down to his advisors and friends, but that’s a notoriously closed (and close-mouthed) set. Although Gandhi wasn’t available for comment, Fortune India spoke with more than 50 politicians, policymakers, and businessmen, many of whom are considered to be close to him. Figuring out Gandhi’s economic agenda is, in a sense, like piecing together a mammoth jigsaw, with clues from his speeches and actions along with insights from those who have worked with him or studied him closely.

NIYAMGIRI, EASTERN ORISSA. It’s a 12-hour drive through forests from Bhubaneswar, Orissa’s capital, to Niyamgiri in the Kalahandi district. The road is more potholes than tar. Kalahandi itself has been in the news because of the number of starvation-related deaths, but today, the Niyamgiri hill takes centre stage. This is the site of a five-year-long battle between the hill’s inhabitants, the Dongaria Kondhs, and the Rs 36,000 crore metals giant, Vedanta Resources. To the Kondhs, Niyamgiri and everything that comes from it is sacred; they see the hill as home to their gods and as a place to live in, not a commodity to be sold. Vedanta, in a startling parallel to the humans in James Cameron’s Avatar, wants the hill for what lies beneath—an estimated 78 million tonnes of bauxite, used in making aluminium. It already has an aluminium plant here, in the midst of the almost relentlessly green forest.

The Kondhs had been fighting alone for three years; two years back, they got some heavyweight support from Gandhi, who visited the hill in 2008 when he learnt of their struggle. The battle between the hamlet and the corporate continued for the next two years, with behind-the-scenes lobbying in Delhi, till 2010, when the environment ministry put a stop to mining, citing problems in land acquisition. Gandhi and the environment ministry have vehemently denied accusations that development was stopped because Orissa’s ruling party, the Biju Janata Dal (BJD), is not part of the UPA coalition.

Soon after the mining ban, this August, Gandhi flew to Niyamgiri, despite the Naxal threat, to congratulate the Dongaria Kondhs. By travelling there, says Bhakta Charan Das, Congress MP from Kalahandi, Gandhi signalled a shift in how the government treated adivasis. “There was always a sense that the feelings of the adivasis are not important. That they are a hindrance to development. He has changed that completely,” says Das, who organised Gandhi’s visit to the remote hill.

With his visit to Niyamgiri, and his speech there, Gandhi plunged straight into what is perhaps the biggest economic debate in India today. Who should control natural resources and development, and who ultimately benefits from liberalisation? “We do not want development that does not hear the voice of the poor. I am your soldier in Delhi. I will carry your voice there,” he said.

(INR CR)

Stirring words, but they puzzle Britain’s Labour peer, India-born author and economist Meghnad Desai. “I am your soldier in Delhi? What does that mean? Who are you fighting? Are you fighting business? Are you fighting reforms? Are you fighting industry?”

Questions are also being raised at the grassroots. Gandhi made Vidarbha, Maharashtra, widow Kalavati Bandurkar famous by mentioning her in a stirring speech in the Lok Sabha in 2008. But it was a nonprofit that finally lifted her out of poverty earlier this year.

“He said he is our soldier in Delhi,” says Aruna Nag, a primary school teacher who used to teach at a tiny government school in Niyamgiri. During the monsoon, the roof of the ramshackle building caved in; parents refused to send their children to school. “For more than six months, I had nowhere to teach and the kids had nowhere to go. Then Vedanta built this,” she points to a newly painted one-room building barely a kilometre from the factory site and less than half a kilometre from where Gandhi spoke. “It’s better than what we had. We are now torn. We don’t want the factory; it will ruin our hill which is sacred to us. But we need what it brings. We don’t need a soldier in Delhi. We need a builder here. Does Rahul Gandhi have an answer to that?”

Nag’s question is one that’s being asked often these days in several parts of the country: What should the model of equitable development be, especially in rural India? “We are not at a phase of growth where we can ignore industrial activity as vital as mining. There seems to be a feeling that growth can be sacrificed, that economic growth is something dispensable. This is worrying.” That’s Jay Panda, MP (Kendrapara constituency, Orissa), considered one of the most erudite voices in the BJD.

On the other side of the fence is agricultural activist Devinder Sharma. “Gandhi has demonstrated that social and cultural linkages in human development cannot be bulldozed in the name of development.”

So far, Gandhi has offered little by way of answers, concentrating, instead, on identifying the problem. “Two Indias are being created,” he said at the 2010 rally in Niyamgiri. “One of the rich and the other of the poor. The voice of the rich is easily heard in the corridors of power. The voice of the poor seldom reaches there.”

An insider at the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation, Delhi-based philanthropic organisation, insisting that he not be named, says: “It’s clear that Rahul Gandhi is moving left of centre in his economic policies. This is what wins votes and balances the free market surge of the last 20 years. With liberalisation as a goal being met, it’s time to address other concerns that are far more critical for future stability and votes.”

INCLUSIVE CAPITALISM IS THE WAY FORWARD, say two of Gandhi’s childhood friends, Sachin Pilot and Jyotiraditya Scindia, members of Singh’s cabinet. “You have to understand how history will judge our generation of Indian politicians,” says Pilot, minister of state for communications and information technology. “Our generation will be judged on whether we could bridge the divide between the rich and the poor India.”

To do that, they’ll need the money and initiative that only big business can give; Vedanta, for instance, built the school in Niyamgiri when the government seemed to have forgotten the area. Gandhi will have to figure out how to woo industry without weakening his plank of development for all.

But it’s becoming increasingly clear that in some areas, the role of the state will be nonnegotiable. A lawyer who has the ear of India’s most powerful business family, the Ambanis, says the signs are already clear. When Mukesh and Anil Ambani fought bitterly over the pricing and supply of gas from one of the Reliance fields, the UPA was in the thick of things, trying to resolve the row. “The message that went out from the Gandhis was very clear,” says the lawyer. “Gas, being a natural resource, first and foremost belongs to the state. Private participation is welcome but the first principle is nonnegotiable.”

Should business be on alert? Yashwant Sinha, former finance minister and senior leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is scathing in his condemnation of Gandhi’s economic policy. “If Indian industry is not worried, it ought to be,” he says. “In the name of inclusive governance, economics is being completely forgotten.”

However, while India Inc. believes the process of reforms is irreversible, it is also scrutinising the nuances in Gandhi’s utterances. Most businessmen take a long-term view. There is a perception that if Gandhi succeeds, consumption will get a boost. “If business pays more in the inception stage and creates assets among the poor whose only assets are natural resources like land and forests, then this has a domino effect on purchasing power. If 40% of Indians can be termed poor, this is not sustainable for the development and growth of business. Where will millions of new customers come from?” asks Harsh Neotia, chairman of Ambuja Realty.

There are others, like Darshan Mehta, CEO of Reliance Brands, part of the Reliance Group, who say that Gandhi is one of the few politicians today who speaks openly against business projects that are not seen as being for the greater good. “Industry has always known politics and politicians to be ambiguous,” he says. “Someone of the stature of Rahul Gandhi rarely comments on specifics. The fact that he is willing to do so, and to take a stand, makes a huge difference to the overall climate. This brings about clarity, critical for transparency in business and at the interface of business and policy.”

ECONOMIST BIBEK DEBROY BELIEVES that the principal dilemma people are trying to resolve is whether Gandhi will go the way of his grandmother, Indira Gandhi, the socialist-leaning nationaliser, or his father, the tech-savvy politician with free-market instincts. “He must do a balancing act of sorts but even there he has to lean towards one or the other and the determining factor in some senses will be demographic.” Debroy previously headed an institute of the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation, and was seen as an advisor to Sonia Gandhi.

Sudha Pai, author and professor of politics at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, may have some idea about which way Gandhi will go. Five years back, shortly after his entry into politics, Gandhi had dropped in at Pai’s home. “He called and said he wanted to meet and came very quietly, with no paraphernalia, just one security person.” Gandhi had read Pai’s well-known treatise, Dalit Assertion and the Unfinished Democratic Agenda, while analysing his party’s demise in its once strong base in Uttar Pradesh, India’s biggest state, which is dominated by a power struggle between Dalits and the upper castes.

Soon after, Gandhi began wooing Dalits in the state, eating with them and sleeping in their village huts. In January 2009, he persuaded former British foreign secretary David Miliband to stay a night at the house of a Dalit woman Shivkumari Kori in his Uttar Pradesh parliamentary constituency of Amethi.

Pai says Gandhi’s economic thinking is closer to his great-grandfather and grandmother than his father. She believes that his focus on the aam aadmi (common man) is an extension of Indira Gandhi’s famous garibi hatao (remove poverty) line.

Indira Gandhi is remembered for the mass nationalisation of economic assets, including banks and insurance companies, but Pai says that her grandson’s policies may not be as extreme. “There is a sense that the process Rajiv started, of liberal economic reforms, is now irreversible. Rahul feels that the time now is to do the balancing act of welfare.”

What is likely to happen, says former Congress cabinet minister, is that “in a Rahul Gandhi age, the parameters of evaluating return on capital will alter”. He says Gandhi will scrutinise government spending as well as how businesses spend, and ask how much resulted in job creation.

One recurring theme since Gandhi’s entry into politics is employment for all. For the last five years, he has been crisscrossing the country to understand first-hand what ails India’s development. His father went on a similar journey between 1980 and 1984. Ashok Tanwar, former Youth Congress president and now a Congress Member of Parliament, is a handpicked member of Gandhi’s entourage. He says job creation is his leader’s core belief. “I have travelled many, many times with him. In each place he asks people what their job is. What do they do? Where do they work? How much money do they make?” says Tanwar. “The belief is that if people do not find work, then there is no hope and no purpose of anything. People must find constructive labour. Look at the Maoist belts—all places of high unemployment.”

That’s also where paradox reigns supreme. Jobs in such areas will come from manufacturing, which means redistribution of land to industry. “The biggest question that needs to be addressed is the legitimate use of natural resources,” says former bureaucrat N.C. Saxena, who authored a project report on Vedanta’s Niyamgiri project in 2010. In response to accusations that the present government is anti-industry, he says: “I am all for mining and the jobs it creates and the wealth it generates. But in Niyamgiri, I found that for years most locals had not agreed to part with the land. There was complete apathy towards the poorest people. This is unacceptable and a major lapse for government and industry. This is not the right path for industrialisation.”

The land acquisition bill, yet to be passed by Parliament, proposes that the state give up the role of playing intermediary in land acquisition in favour of direct interaction between the seller (usually a farmer) and the buyer (business). “Farmers now sell to the government at agricultural rates, which are lower than rates for industrial use. The land is then passed on to industry for commercial use and the value shoots up. Farmers protest, vested interests come in and there is chaos,” says C.V. Madhukar, a Harvard Kennedy School graduate and former banker who runs the legislative research body PRS Legislative Research. “The law will ensure that industry buys land from farmers at mutually agreeable rates. In the long run, pricing policy has to be fixed and that’s the direction in which policy is moving.”

THE NATIONAL ADVIOSRY COUNCIL (NAC) may offer some insight to Gandhi’s economic thinking. “If there is anyone who is the guiding force behind Gandhi’s thinking in these matters, it is this set,” suggests historian Mahesh Rangarajan. The NAC was revived after the UPA won the general elections for the second time in 2009. It was an election fought and won on economic issues, especially the decision to waive farmer loans and create the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGA), which assures 100 days of paid labour for the poor, with a minimum wage of Rs 60 a day. This scheme is seen as the brainchild of the NAC, often called the most powerful extra-constitutional body of the government.

Members like the Left-leaning Belgian-born economist Jean Dreze, key architect of the MNREGA, say there are major loopholes in implementation and that the scheme should be strengthened. The NAC, with members like Magasaysay Award winner Aruna Roy and social activists Deep Joshi and Harsh Mander have pushed for an expanded new food security bill which provides free food to the poor and adds Rs 30,000 crore to budgetary expenditure.

This could be dangerous for India’s reform process, says Arun Shourie, senior leader of the BJP. His big problem with the NAC is, he says, that, “they are single-issue fundamentalists. The entire process of governance is being seen as an either/or process. Either environment or development. Either tribal and farmer welfare or industrial growth. This mindset is dangerous.”

More to the point, he believes that the MNREGA needs to be overhauled if it is to be successful. “Unless delivery mechanisms are fixed—and massive, multi-million dollar leakages are blocked—giant sop schemes only mean that in the name of inclusive growth every kind of populist expenditure is justified. Without tight delivery systems, this only leads to decentralisation of corruption,” he says.

Congress leaders admit as much. “Even in Tripura, the state that scores highest in providing households with the full 100 days of employment, the success rate is no more than 36.6%. Far more upsetting is that in the most poverty-stricken states of India, the share drops to a mere 14% in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh and to 8% or less in Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Bihar,” says Mani Shankar Aiyar, former petroleum and panchayati raj minister and Congress MP, and believed to have been one of Rajiv Gandhi’s inner circle.

This, says a former BJP minister, might affect Gandhi’s relationships with business. “The state is burdened with more expenditure but delivery is weak. Violence does not stop. Because of Left-leaning policies, reforms are slow and business is damaged. This means there will be tension between business and Gandhi in the Obama sort of way.”

As Gandhi looks for the right path to industrialisation, he’s not going to be able to please everyone. His challenge is to figure out whom he can afford to please less.