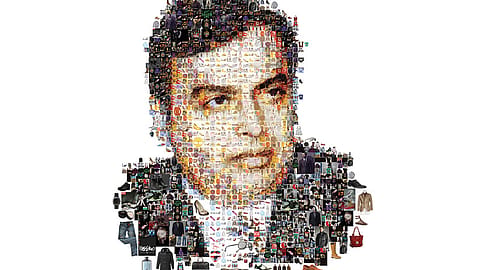

Of Leopards, luxury and Ambani

The entry of Reliance into fashion and luxury in India could rewrite the rules of the game. Should LVMH worry?

THE TALE OF A LEOPARD’S HUNTING SKILLS brought 51-year-old Darshan Mehta to Reliance Industries four years ago. He heard it in one of his early discussions with Mukesh Ambani who was trying to convince Mehta, then at Arvind Brands, to head Reliance Brands, the group’s foray into luxury. Ambani is a wildlife buff and regularly hits game parks in Africa. “Have you ever noticed the leopard?” Ambani asked. “It does not roar or make much noise. It just sits quietly, usually on the top of a tree, where it can hardly be seen. And it waits. It can wait for a verylong time. Then when it suddenly jumps, it almost always kills. Its strike rate is unmatched among the big cats.”

Sitting in his south Mumbai office facing a serene, sylvan stretch of shoreline, Mehta, now CEO of Reliance Brands, says, “Ever since, it [the leopard’s example] has often come up in conversation as a great example of how to do business.” Ambani preaching patience as the best form of aggression reinforces the popular perception that Reliance always plays for the long term.

That may explain the entry of an industrial conglomerate of Reliance’s nature and size into fashion and luxury in India, a sector that continues to be described as ‘nascent’ more than a decade after Louis Vuitton opened its first shop and the first India Fashion Week was held. According to Mehta, by 2020 there will be 50 million to 60 million consumers of luxury and premium fashion here—almost the same number as in America. From 2010 to 2011, the luxury market in India grew by 20% to reach $5.75 billion (Rs 29,250 crore), according to consulting firm A.T. Kearney. Mehta draws his optimism from the fact that luxury products (clothes and accessories) grew at 29% to $2 billion. “Even today, most Indians don’t consume fashion the way people in the West or in Southeast Asia do. That is set to change. We will be consuming clothing brands like never before. It’s an enormous opportunity.”

In February this year, Reliance Brands announced a joint venture with the New York-based premium fashion seller, the $370 million Iconix Brand Group. Among Iconix’s better known labels are Mossimo and London Fog. Then, in March, it inked an exclusive deal with the $30 billion French luxury giant LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) to sell Thomas Pink shirts here. Reliance Brands already has in its stable more than 29 labels, including marquee names such as Italy’s Ermenegildo Zegna and Diesel. Many of these compete with LVMH, but more on that later. Most of these deals (Zegna, Diesel, Iconix) have been structured as joint ventures (both sides invest and share the spoils), while some (Pink) are exclusive, long-term franchise agreements. Reliance Brands’ investments aren’t known.

What’s unique is that these agreements run for at least 20 years—unlike five-year contracts that other labels have negotiated. The arrangements have Reliance written all over. They demonstrate its ability to swing favourable deals, signal it’s a long-haul player and also show it’s learning from others. For example, Pradeep Hirani, owner of the Kimaya fashion chain, entered into five-year contracts with labels such as Max Mara and Roberto Cavalli, but ultimately exited, despite sitting on Rs 60 crore of private equity (PE) funds. It takes two to three years just to establish a brand in India, no matter how well it is known globally, and returns start coming in only after five years. “We were tilling the soil, but missing the crop. So we decided to get out,” says Hirani. According to industry estimates, the upfront spends per luxury label on rentals, advertising, marketing costs, logistics, and salaries in the first two to three years could be anywhere between Rs 3 crore and Rs 10 crore. Roberto Cavalli now has another five-year contract with a Delhi-based fashion outfit.

Reliance’s approach shows who’s big daddy here: “We are very clear in our dealings. We do not do short term. We have our terms. If someone sees value in the future like we do, we are happy to talk. Otherwise not,” says Mehta.

Given its size, ambitions, ability to influence, and deep pockets, Reliance redefines any business it enters. In recent years, telecom is the best example, but even in retail, where Reliance’s passage hasn’t been smooth, it forced competitors to redraw their strategies. Yet, with more than $58 billion in revenue, Reliance is more associated with the industrial business of sweating fixed assets from oil to textiles, than the vanilla-scented world of luxe. Indeed, even at East India Hotels (Oberoi), where Reliance has built up a 15% stake and may end up owning the company (See Fortune India, February 2012), questions are frequently asked about Reliance’s understanding of luxury hotels.

Mehta sees it differently, and argues that if you break it down to individual elements, Reliance Brands has what it takes. His team, many of whom are from Arvind, has launched labels such as Tommy Hilfiger in India, and knows how to sell high-end brands. When it comes to fabric, his two decades plus at Arvind and the institutional knowledge that Reliance has—he points to Vimal fabric, even though that’s more mass market than luxe—is unbeatable. (Mehta’s quite a dandy himself. He is rumoured to own 100 suits and 50 pairs of jeans, all housed in a 25 metre walk-in closet, though he says he hasn’t counted recently.) Finally, a large element of Reliance Brands’ push entails having stores in the right locations.

Take Mumbai’s latest megamall, Phoenix Market City (in Kurla), which opened last November. Reliance has 11 stores there, including iStores which sell Apple products, and a 5,000 sq. ft. Board Riders store for action brands such as Quiksilver (fashion), featuring a built-in skateboarding ramp. When Reliance Brands real estate sharpshooter Navin Balani aims, he almost always does it along with the Reliance group. It allows him to get better locations at better prices, because the group buys in bulk.

“When we hunt for location, we are not just Reliance Brands, we are Reliance,” says Mehta.

Renzo Rosso, founder of Diesel and a Reliance partner, says it’s this approach that makes Reliance a “special company. Thanks to its high-level connections [Reliance] has insights that a foreign brand entering the market alone can never have.” This, he adds, allows for less “road mistakes”. Kalyani Chawla, vice president, marketing and communication, Christian Dior Couture India, a part of LVMH, believes that Reliance can get things done in India, from customs clearances, better policy regulations and taxation rates, to a dialogue between the government and industry.

(INR CR)

BUT THE BUSINESS OF HIGH FASHION is also about sweating the intangibles. It’s not so much about building scale (Reliance’s DNA), but about creating an aura that consumers buy into. Which is why luxury is at once tantalising (the high margins), yet frustrating (not everyone gets the aura right). That’s where Reliance Brands will face its toughest competition—from LVMH, also committed to building a big business in India.

In some ways, Mukesh Ambani and LVMH’s chairman Bernard Arnault are similar. Both are seen as aggressive businessmen, and that makes people uncomfortable in the snooty world of luxury. So, if the folks at East India Hotels fret about their hotels, the men at Hermès were equally concerned after LVMH acquired 20% of Hermès. They feel Hermès is aristocratic and a truly artisanal brand, whereas Arnault is a corporate raider, with an eye only on the balance sheet. A few months ago, on a visit to India, Hermès CEO Patrick Thomas told Fortune India that “God forbid”, if LVMH were to buy Hermès “it would lose its soul” within five years.

It’s a fascinating pas de deux between Reliance Brands and LVMH. While Reliance Brands may sell Thomas Pink shirts, Zegna will compete against Louis Vuitton Men. Also, the rivalry may not be restricted to brands. It’ll spill over into talent, and most critically, real estate, which already is in short supply for high-end labels.

Neither side wants to comment on this. Mehta says that Reliance Brands is in a race against itself to grow faster. So why did it tie up with Thomas Pink? “Our decision was driven entirely by our belief in the robustness of that brand, its traction with a large number of consumers in India who aspire to accessible luxury, and the strength of the partnership.”

On his part, Jonathan Heilbron, president and CEO of Thomas Pink, says he is delighted to work with Reliance Brands. “We expect to be able to expand faster than if we were operating on our own.”

Meanwhile, there’s no slowing down LVMH. Some of its moves have been routed through its PE fund, L Capital. It has so far picked up 40% in garment house Genesis Colors (which owns home-grown apparel label Satya Paul) and 7% in ethnic-wear major Fabindia. LVMH has also invested directly in leather accessories maker Hidesign. Sanjay Kapoor, managing director, Genesis Luxury (a division of Genesis Colors) says that with the money comes strategic advice, invaluable branding and marketing support, and even inputs on how to make world-class yarn.

Ravi Thakran, L Capital Asia’s managing partner, says he will spend $250 million in buying into three or four brands in India in the next one year. “We will invest in any company that has the potential to be taken to a global scale. Indian entrepreneurs know how to make a product and they know their customers. We know how to build global brands and that is our value addition.” That opens another front: A race between Reliance (it too wants to create brands of its own) and LVMH to invest in local labels.

Thakran sees the LVMH-Reliance dynamics differently. “We cannot develop a market single-handedly and the more people like Reliance come into the market, the better, because they will be able to transform things on a pan-India level.” He gives the example of Chinese investment company CITIC Group, which co-invested with L Capital in women’s fashion brand Ochirly in February to show how the world’s biggest luxury and fashion company works with regional giants, rather than compete with them. (The Citic comparison may not be appropriate. It is a pure finance and investment company, while Reliance is an industrial conglomerate with an owner who has declared that consumer businesses will be its future.) Adds Thakran: “We would be happy to collaborate and invest with Reliance.”

Call it Reliance’s aura if you like. Ultimately, there’s no one who will say it is competition.