Bajaj Auto: In top gear

Rajiv Bajaj has a 360° plan to make Bajaj Auto live up to its tagline ‘the world’s favourite Indian’.

One of Rajiv Bajaj’s favourite movie scenes is the opening sequence from the 2004 Hollywood blockbuster Troy. In the scene, the Trojan and Greek armies decide to settle the fight through a duel between Achilles (played by Brad Pitt), the greatest of all Greek warriors, and Boagrius, a Trojan fighter.

With Achilles nowhere to be found, a messenger boy is sent to summon the warrior. As Achilles mounts his horse to take off for battle, the petrified young boy cautions the Greek that Boagrius was the biggest man he’d ever seen and he wouldn’t want to fight him. “That’s why no one will remember your name,” Achilles says in response and rides away.

Bajaj, 52, has shown this scene to many a colleague to coax them into pushing the envelope further. And much like Achilles’ quest to be remembered as the greatest warrior that ever lived, Bajaj is obsessed with creating a reputation for his company as being one of the most competent automakers in the world.

He hasn’t done badly either. Bajaj Auto is the third-largest motorcycle company in the world with a top line of more than ₹30,000 crore (see chart); the largest manufacturer of three-wheelers in the world; an exporter to over 70 countries; innovator of new products like a quadricycle; and a global partner to marquee superbike brands including KTM, Husqvarna, and Triumph. And the Pune-based company has done all this while maintaining decent profitability.

It helps that the managing director of Bajaj Auto, who took over from father Rahul Bajaj in 2005, has been given a free hand to shape the company’s destiny as he deems fit. The father and son have had differences, but the senior Bajaj hasn’t sought to interfere in his son’s decision-making process. Bajaj’s decision to focus on motorcycles and exit the scooter segment—once the company’s mainstay with brands such as Chetak (which has made a comeback after more than a decade in an e-avatar) and Priya—didn’t sit well with his father.

“The way in which Rahul Bajaj gave way to Rajiv shows a lot of maturity and vision. Rahul has publicly said that he didn’t like the decision to exit scooters, but he didn’t prevent the management from taking that decision, even under his chairmanship,” says Rajiv Agarwal, professor of strategy and family business at S.P. Jain Institute of Management and Research.

Bajaj has also benefitted from an unencumbered path to leadership at Bajaj Auto because of a demarcation of business interests undertaken in 2008. That year, the financial services business, which is now under Bajaj Finserv and Bajaj Finance, and controlled by Bajaj’s younger brother Sanjiv, was demerged from Bajaj Auto. Both brothers continue to be directors on the boards of each other’s companies.

Recommended Stories

Arun Kejriwal, director, Kejriwal Research and Investment Services, says the decision to separate the financial services business from the auto business has worked to the advantage of both and was the best decision taken by Rahul Bajaj. “The demerger has led to greater overall wealth creation for shareholders,” says Kejriwal. “The move also negated the chances of any future family feud as both brothers retain individual charge of their respective businesses.”

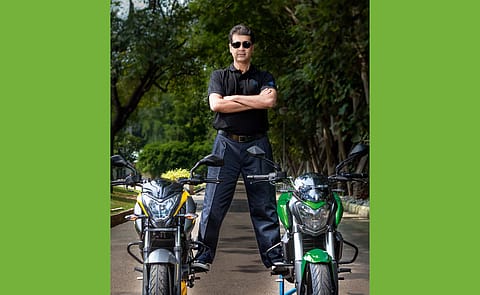

On a pleasant October afternoon, Bajaj meets Fortune India at the company’s lush green and sprawling headquarters in Akurdi, on the outskirts of Pune. Dressed in his trademark black T-shirt with a blue Bajaj logo and dark blue trousers, Bajaj is nursing a cold with warm water and honey. But that doesn’t dampen the enthusiasm with which he goes about explaining the strategy he has followed to get Bajaj Auto to its current position, the difficult and unpopular calls he has had to take, and the company’s future as he sees it—in terms of new products, including electric vehicles (EVs), and markets.

“I like the term tallest motorcycle company better. Not biggest or largest. We must be tall in every sense of the term— whether it is in terms of technology or global recognition,” he explains.

Almost like a B-school professor, Bajaj grabs a marker and draws a triangle on a whiteboard. In the middle of this triangle he draws a large circle and says that this—denoting motorcycles—is at the heart of Bajaj Auto’s business. Bajaj Auto is a volumes player, he says. Of the 5 million vehicles that Bajaj Auto produced in FY19, 4.23 million were motorcycles. “This business gives us our skills and cost structure, which we need to leverage to expand into adjacent niches and gain leadership position over there,” Bajaj says.

(INR CR)

In FY19, Bajaj Auto had the secondhighest share of motorcycles sold in India at 18.68%, and a 12% share of the overall twowheeler market (including scooters). The largest player was Hero MotoCorp, which had a 36.6% share of the two-wheeler market. Though Bajaj Auto has done well over the past couple of years on the back of recent launches and gained market share, Hero has traditionally enjoyed greater volume share due to the success of its entry-level commuter bikes (100cc-125cc).

Bajaj Auto, on the other hand, has a commanding share of the premium bikes segment with bestselling brands such as the Pulsar and the Dominar, which are doing well in India and abroad. But the company has realised the need to up its game in the executive/commuter segment as well and is planning to compete with the likes of Hero and Honda not only on price and mileage, but also with differentiated product innovation. For instance, its Platina 110 H Gear is the only product in its class that allows the rider to cruise at a low speed in high gear, without the engine stuttering.

Bajaj Auto, which has a current market value of over ₹85,000 crore, has focussed on developing its own designs and technology for bikes from scratch, which has given it the flexibility to tweak its plans depending on the customer segment and geography it is catering to. “We started at the basics and gave our vendors access to affordable technology that helped us break the black box,” says chief technology officer Abraham Joseph. “We are deep believers in differentiation and segmentation, and that is demonstrated by the Pulsar.”

The debt-free company, which has cash reserves of around ₹17,000 crore, has made its fair share of mistakes. Its Discover 125cc bike was selling well before a 110cc variant was launched. The muddled product proposition along with advertising that confused the buyer on what the Discover stood for virtually killed the brand. “In an attempt to milk the success of the Discover we lost the plot,” Bajaj admits. “The learning from this is that one should not stray from one’s Lakshman Rekha.”

Bajaj Auto finally seems to have got a product in its 125cc portfolio right with the new Pulsar 125, which is selling like hot cakes. Bajaj says that with the Pulsar 125, it is providing customers access to a powerful bike. Wiser from its experience and to prevent dilution of the Pulsar’s brand positioning (it is generally known for its more powerful 150cc-220cc variants), Bajaj Auto isn’t advertising the Pulsar 125 in mass media; instead people can visit showrooms to discover it for themselves.

Let’s get back to Bajaj’s strategy triangle again. The bottom left corner represents three-wheelers and the recently launched Qute—a quadricycle that can serve as a better alternative to three-wheelers in the commercial vehicles segment. Globally, Bajaj Auto sold over 780,000 three-wheelers in FY19 and had a market share of 85% in India alone. The presence in this segment is justified, Bajaj says, because this business enjoys a lot of commonalities with the motorcycles business—in terms of facilities, skills, hardware, and software.

The Qute, which is 250 kg lighter than a Maruti Suzuki Alto, was already being exported to over 20 countries when it was launched in India in April after battling and overcoming long-pending regulatory hurdles. With the Qute, Bajaj Auto aims to cater to a more evolved segment of commercial vehicle operators who want to offer their customers a safer and better ride. “Fleet owners find the Qute very efficient as it returns a mileage of 35 km per litre (kmpl), compared to the 25 kmpl-28 kmpl given by a three-wheeler,” says Rakesh Sharma, executive director, Bajaj Auto. He adds that though the Qute may cannibalise the company’s threewheeler business to a certain extent, it will also cannibalise the small car and used car markets, where maintenance costs are high.

Uber has already rolled out Qute cabs in Bengaluru under a new category called Uber XS. The service is witnessing demand that is 10 times the supply and the average user rating for Qute rides is 4.8, says Bajaj.

The top corner of the triangle represents products that are at the top of the pyramid—performance bikes and superbikes offered in partnership with brands like KTM. Bajaj Auto owns 48% in the Austrian bike maker and has a partnership that spans across the development and manufacturing of bikes for emerging markets (like those with a lower displacement of around 125cc, and at a lower price point); and both brands handle each other’s frontend distribution in their respective markets of strength. Bajaj Auto also plans to introduce European performance bike brand Husqvarna, owned by KTM, into India.

The other partnership that Bajaj Auto is exploring, which could be a potential game changer for the company, is with Triumph, the iconic British bike maker. Triumph has a limited number of showrooms in India but is keen on partnering with Bajaj Auto to make a larger splash in this market and wants its potential Indian partner to give the same kind of scale and platform as it gave to KTM, says Bajaj. Back-end discussions between the Bajaj Auto and Triumph teams on the designs of some new products, which could be made by Bajaj Auto in India, have already begun and a formal partnership could be announced by the end of the current financial year.

The last, bottom right corner of Bajaj Auto’s strategy triangle belongs to EVs. On October 16, Bajaj Auto unveiled a new electric scooter, through which it also revived the Chetak brand. The new product, which will hit showrooms in January, is a part of Bajaj Auto’s programme called ‘Urbanite’, through which it seeks to develop urban mobility solutions using EVs.

There has been a lot of chatter in the country with respect to the future of electric mobility. While no one disagrees that EVs are the future, there is a lot of debate on the desired rate of proliferation of EVs, so that the ecosystem around electric mobility—such as the charging infrastructure and availability of reasonably priced batteries—matures further, and internal combustion engine products also get a future runway.

“We first need to create demand for electric vehicles and then the infrastructure will fall into place,” Bajaj avers. “For this, automakers need to be allowed to import technology at low duties, since no vendor is going to commit to mass-scale production unless they have visibility of demand.” Sharma says that Bajaj Auto will eventually be looking at electric versions of all its products, including threewheelers and the Qute.

Launching an electric scooter, instead of a bike, may have been a masterstroke on Bajaj Auto’s part since electric bikes haven’t been well received by customers yet. Though Chetak, in its new avatar, is a scooter of a very different kind, Bajaj, who joined the business in 1990, is fully prepared to face questions over Bajaj Auto’s re-entry into the segment under his watch. Especially, since he was instrumental in the company exiting the scooter segment completely in 2009.

“I cannot convince everyone. But I will tell those who are willing to listen that we are not jumping into the red ocean [a business term for an existing industry where boundaries are defined, and competition is severe] of scooters. I am going into a different niche, which is true to our strategy,” says Bajaj.

But considering scooters are still such a big segment of the two-wheeler market in India, as well as in other emerging countries like those in the ASEAN, why did Bajaj Auto exit this business?

Bajaj says though physically he may have pulled the plug on this business, “intellectually” it was his father who forced him to take the decision. For the first 30 years till 1990, Bajaj says his company’s pursuits could be best described by its marketing tagline at the time, ‘Hamara Bajaj’, which encapsulated the company’s vision of being every Indian’s choice for an easy and hassle-free commute on scooters.

Sometime in 1993-94, Bajaj asked his father what the latter wanted him to do with the company. “My father told me: ‘Do what you think is best, but be the best in what you do’,” he reminisces. “He said that Bajaj Auto should be world class and that can happen when the company exports 20% of its products. It became very clear to me that as we broaden the range of markets we want to address, we need to narrow down our range of products and specialise in a few things.”

It is obvious that Bajaj didn’t have much confidence in retaining scooters as the company’s vehicle for global growth and chose motorbikes instead. His strategy paid off as Bajaj Auto exports 40% of its products at present and consequently calls itself ‘The World’s Favourite Indian’.

Despite competition from a bevy of well-heeled Japanese and European brands, how did Bajaj Auto make a mark for itself in the world of exports? Sharma, who joined Bajaj Auto in 2007 and played a key role in seeding international markets, says, “The foremost reason why we made it big in exports is management will.” He explains that Bajaj Auto didn’t spread itself too thin but invested time and resources to understand the nuances of specific markets and utilised those lessons while moving on to others. “Today, 80%-85% of our export revenue comes from markets where we are either No. 1 or No. 2. In the last five years alone, we have developed 23 new markets for three-wheelers, including in diverse countries like Ghana, Bolivia, Iraq, and the Philippines.”

Bajaj Auto’s chief financial officer Soumen Ray says exports and diversification into new products have helped the company de-risk its business by not being overtly reliant on any one region or product. “Our top line and bottom line are not dependent on any five SKUs [stock keeping units] and geography combinations,” he says. That’s perhaps why Bajaj Auto seems to be bearing better than some of its peers what is arguably one of the worst slowdowns in the Indian auto industry.

“After gaining market share in FY19, we expect further gains from Bajaj Auto in FY20, driven by new launches,” says a recent research note by HDFC Securities. “The OEM [original equipment manufacturer] is well equipped for BS VI given existing supplies to KTM. Further, its diversified product portfolio (threewheelers are around 50% of volumes) provides cushion against volatility in domestic 2Ws [two-wheeler segment].”

The final piece of Bajaj Auto’s strategy is its focus on profitable growth and efficient operations. Executive director Pradeep Shrivastava, who oversees operations, says that over the years, the number of vendors supplying components to the company has been rationalised to 200 from around 800 earlier. Also, each of Bajaj Auto’s three plants—at Chakan, Aurangabad, and Pantnagar—follows a cluster approach where the component suppliers are located within a 5 km-radius of the mother plant.

At Chakan, there are no stores for spare parts as everything that enters the factory is directly put on to the production line. “We work with our vendors to give them technology and supervise their production processes to ensure there are no redundancies,” says Shrivastava, who’s been with the company since 1986. “Our operations have to be agile, flexible, and efficient and, for this, we have an in-house engineering team that develops low-cost technology solutions.”

Many an analyst has pointed out that since the demerger, Bajaj Finance and Bajaj Finserv’s market capitalisation (at ₹2.33 lakh crore and ₹1.29 lakh crore, respectively) has far outpaced that of Bajaj Auto. How does Bajaj react to these comparisons?

“Comparisons are the death of joy,” Bajaj says candidly. “I am not interested in comparing Bajaj Auto with Bajaj Finance any more than I am interested in comparing myself with another auto company. How does that help me? But when the immigration officer in a Latin American country looks at my passport and recognises that I am from the company that makes the tuk-tuks in his country, it is priceless. No market cap can compare to that.”

(This story was originally published in the November 2019 issue of the magazine.)