India’s day of reckoning

In Fortune’s April 1942 issue, in a seven-page article interspersed with wartime advertisements, Jawaharlal Nehru made a case for India’s independence. He reminded readers that if the country’s industry and talent had been free to develop, its war support—so crucial to the Allies—would have been greater. The economic and political interests of a free and strong India were thus in harmony, not at odds, with those of the free world. India had much in common with China, he argued, and the future belonged to Asia. His main contention—that the world can’t afford to ignore India—remains relevant. Since he wrote this piece, India has emerged as the world’s 11th largest economy, and is poised to grow further. In the following pages, we bring you Nehru’s original article.<br><br><br>The Editors, Fortune India, 2010

The most urgent problem facing the United Nations, as this issue goes to press, is the defence of India against the converging thrusts of the Axis powers. It is not only a military problem; it is the culmination of a historic political conflict within the British Empire over India’s demands for independence for her 40 million people. The British Government is grappling with those demands at this moment; indeed, some sort of agreement may have been announced by the time this appears in print. On the effectiveness of the solution, the fate of the democratic world may ultimately depend.

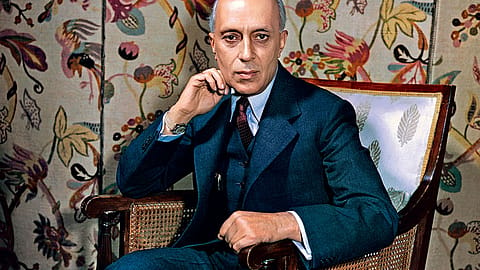

With those facts in view FORTUNE presents the accompanying statement of India’s position relative to the war, written by the head of the Indian nationalist movement, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, son of a wealthy lawyer, who was schooled in Harrow and Cambridge. He has been an uncompromising nationalist since World War I, and has spent much of the past twenty years in jail. Released last December, Nehru became President of the Indian National Congress Party, succeeding Gandhi who, even under threat of aggression, clung to his creed of nonviolence. Nehru’s political importance was highlighted by the visit paid him in February by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek and Madame Chiang. Advocates of Indian independence consider him the potential Prime Minister.

Pandit Nehru’s article, angrily critical of the British Government, is published here not to add to the already overwhelming difficulties of our ally, but to contribute in the common cause to an understanding of a vital question affecting us all.

The Editors, Fortune, 1942

New Delhi, March 7 (by cable)

I welcome the opportunity of writing in the columns of FORTUNE on the vital problems that confront India. These problems are no longer our concern only; they are of world concern, affecting the entire international situation today. More so will they affect the shaping of future events. Whether we consider them from the point of view of the terrible world conflict that is going on, or in terms of the political, economic, and commercial consequences of this war, the future of 400 million human beings is of essential importance. These millions are no longer passive agents of others, submitting with resignation to the decrees of fate. They are active, dynamic, and hungering to shoulder the burden of their own destiny and to shape it according to their wishes.

The Indian struggle for freedom and democracy has evoked a generous response from many an American, but the crisis that faces us all is too urgent for us merely to trade in sympathy or feel benevolent toward each other. We have to consider our major problems objectively and almost impersonally and endeavor to solve them, or else these problems will certainly overwhelm us, as indeed they threaten to do. That has been the lesson of history, and we forget it at our peril. It is therefore not merely from a humanitarian point of view, though humanitarian itself is good, but rather in the objective spirit of science that we should approach our problems.

The next hundred years, it has been said, are going to be the century of America. America is undoubtedly going to play a very important role in the years and generations to come. It is young and vital and full of the spirit of growth. The small and stuffy countries of Europe, with their eternal conflicts and wars, can no longer control the world. Europe has a fine record of achievement of which it may well be proud. That achievement will endure and possibly find greater scope for development when its accompaniment of domination over others is ended.

the next century is going to be the century of America, it is also going to be the century of Asia, a rejuvenated Asia deriving strength from its ancient cultures and yet vital with the youthful spirit of modern science. Most of us are too apt to think of Asia as backward and decadent because for nearly two hundred years it has been dominated by Europe and has suffered all the ills, material and spiritual, which subjection inevitably brings in its train. We forget the long past of Asia when politically, economically, and culturally it played a dominant role. In this long perspective the past two hundred years are just a brief period that is ending, and Asia will surely emerge with new strength and vitality as it has done so often in the past. One of the amazing phenomena of history is the way India and China have repeatedly revived after periods of decay, and how both of them have preserved the continuity of their cultural traditions through thousands of years. They have obviously had tremendous reserves of strength to draw upon. India was old when the civilization of Greece flowered so brilliantly. Between the two there was intimate contact and much in common, and India is said to have influenced Greece far more than Greece did India. That Grecian civilization, for all its brillian ce, passed away soon, leaving a great heritage, but India carried on and her culture flowered again and again. India, like China, had more staying power.

Asia is no suppliant for the favors of others, but claims perfect equality in everything and is confident of holding her own in the modern world in comradeship with others. The recent visit of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang to India was not only of historic significance but has given us a glimpse of the future when India and China will cooperate for their own and the world’s good. The Generalissimo pointed out a remarkable fact: that India and China, with a common land frontier of 3,000 kilometers, had lived at peace with each other for a thousand years, neither country playing the role of aggressor, but both having intimate cultural and commercial contacts throughout these ages. That in itself shows the peaceful character of these two great civilizations.

Keeping this background in mind, it will be evident how unreal and fantastic is the conception of India as a kind of colonial appendage or offshoot of Britain, growing slowly to nationhood and freedom as the British Dominions have done. India is a mother country, which has influenced in the past vast sections of the human race in Asia. She still retains that storehouse of cultural vitality that has given her strength in the past, and at the same time has the natural resources, the scientific, technical, industrial, and financial capacity to make her a great nation in the modern sense of the word. But she cannot grow because of the shackles that tie her down, nor can she play her part, as she should, in the war crisis today. That part can be a great one not only because of the manpower at India’s disposal but because, given a chance, she can rapidly become a great industrial nation.

(INR CR)

TO DEFEND THE STATUS QUO, IS TO SURRENDER

The world war is obviously part of a great revolution taking place throughout the world. To consider it in only military terms is to miss the real significance of what is happening. Causes lie deep, and it would be foolish to imagine that all our present troubles are due to the vanity and insatiable ambition of certain individuals or peoples. Those individuals or peoples represent evil tendencies. But they also represent the urge for change from an order that has lost stability and equilibrium and that is heartily disliked by vast numbers of people. Part of the aggressors’ strength is certainly due to their challenge to this old system. To oppose these inevitable changes and seek to perpetuate the old, or even to be passive about them, is to surrender on a revolutionary plane to the aggressor countries. Intelligent people know these aggressors are out to impose tyranny far worse than any that has existed, and therefore they should be opposed. To submit to them is to invite degradation of the worst type, a spiritual collapse far worse than even military defeat. We see what has happened in Vichy France. We know what has taken place in Central Europe and in Northern China. And yet that fear of a possible worse fate is not enough, and certainly it does not affect the masses of population who are thoroughly dissatisfied with their present lot. They want some positive deliverance to shake them out of their passivity, some cause that immediately affects them to fight for. A proud people do not accept present degradation and misery for fear that something worse may take its place.

Thus the urgent need is to give a moral and revolutionary lead to the world, to convince it that the old order has gone and a new one really based on freedom and democracy has taken its place. No promises for the future are good enough, no half measures will help; it is the present that counts; for it is in the present that the war is going to be lost or won, and it is out of this present that the future will take shape. President Roosevelt has spoken eloquently about this future and about the four freedoms, and his words have found an echo in millions of hearts. But the words are vague and do not satisfy, and no action follows those words. The Atlantic Charter is again a pious and nebulous expression of hope, which stimulates nobody, and even this, Mr. Churchill tells us, does not apply to India.

If this urgent necessity for giving a moral and revolutionary lead were recognized and acted upon, then the aggressor nations would be forced to drop the cloak that hides many of their evil designs, and new forces of vast dimensions would rise up to check them. Even the peoples of Europe now under Nazi domination would be affected. But the greatest effect would be produced in Asia and Africa. And that may well be the turning point of the war. Only freedom and the conviction that they are fighting for their own freedom can make people fight as the Chinese and Russians have fought.

TWO AND A HALF YEARS HAVE GONE TO WASTE

We have the long and painful heritage of European domination in Asia. Britain may believe or proclaim that she has done good to India and other Asiatic countries, but the Indians and other Asiatics think otherwise, and it is after all what we believe that matters now. It is a terribly difficult business to wipe out this past of bitterness and conflict, yet it can be done if there is a complete break from it, and the present is made entirely different. Only thus can those psychological conditions be produced that lead to cooperation in a common endeavor and release mass effort.

It was in this hope that the National Congress issued a long statement in September, 1939, defining its policy in regard to the European war and inviting the British government to declare its war aims in regard to imperialism and democracy and, in particular, to state how these were to be given effect in the present. For many years past the Congress had condemned Fascist and Nazi doctrines and the aggressions of the Japanese, Italian, and German governments.

It condemned them afresh and offered its cooperation in the struggle for freedom and democracy. But it stated: “If the war is to defend the status quo of imperialist possessions and colonies, of vested interests and privilege, then India can have nothing to do with it. If, however, the issue is democracy and world order based on democracy, then India is intensely interested in it. The Committee is convinced that the interests of Indian democracy do not conflict with the interests of British democracy or world democracy. But there is an inherent and ineradicable conflict between democracy for India, or elsewhere, and imperialism and fascism. If Great Britain fights for the maintenance and extension of democracy, then she must necessarily end imperialism in her own possessions and establish full democracy in India, and the Indian people must have the right of self-determination to frame their own constitution through a Constituent Assembly without external interference, and must guide their own policy. A free democratic India will gladly associate herself with other free nations for mutual defence against aggression and for economic cooperation.”

That offer was made two and a half years ago and it has been repeated in various forms subsequently. It was rejected—and rejected in a way that angered India. The British government has made it clear beyond a doubt that it clings to the past; and present and future, in so far as Britain can help it, will resemble that past. It is not worth while to dwell on the tragic history of these two and a half years that have added to our problems and the complexity of the situation. Events have followed each other in furious succession all over the world and, in recent months, parts of the British Empire have passed out of England’s control. And yet, in spite of all this, the old outlook and methods continue and England’s statesmen talk the patronizing language of the nineteenth century to us. We are intensely interested in the defence of India from external aggression but the only way we could do anything effective about it is through mass enthusiasm and mass effort under popular control.

We cannot develop our heavy industries, even though wartime requirements shout out for such development, because British interests disapprove and fear that Indian industry might compete with them after the war. For years past Indian industrialists have tried to develop an automobile industry, airplane manufacture, and shipbuilding—the very industries most required in wartime. The way these have been successfully obstructed is an astonishing story. I have been particularly interested in industrial problems in my capacity as Chairman of the National Planning Committee. This committee gathered around it some of the ablest talent in India—industrial, financial, technical, economic, scientific—and tackled the whole complex and vast problem of planned and scientific development and coordination of industry, agriculture, and social services. The labors of this committee and its numerous subcommittees would have been particularly valuable in wartime. Not only was this not taken advantage of but its work was hindered and obstructed by the government.

Two and a half years ago we had hoped to be able to play an effective role in the world drama. Our sympathies were all on one side; our interests coincided with these. Our principal problem is after all not the Hindu-Moslem problem, but the planned growth of industry, greater production, juster distribution, higher standards, and thus gradual elimination of the appalling poverty that crushes our people. It was possible to deal with this as part of the war effort and coordinate the two, thus making India far stronger, both materially and psychologically, to resist aggression. But it could only have been done with the driving power that freedom gives. It is not very helpful to think of these wasted years, now that immediate peril confronts us and we have not time, as we had then, to prepare for it. We may have to meet this peril differently now, for in no event do we propose to submit to aggression.

A FREE INDIA CAN SOLVE ITS OWN PROBLEMS

It is said that any transfer of power during wartime involves risks. So it does. To abstain from action or change probably involves far greater risks. The aggressor nations have repeatedly shown that they have the courage to gamble with fate, and the gamble has often come off. We must take risks. One thing is certain—that the present state of affairs in India is deplorable. It lacks not only popular support but also efficiency. The people who control affairs in India from Whitehall or Delhi are incapable even of understanding what is happening, much less of dealing with it.

We are told that the independence of Syria is recognized, that Korea is going to be a free country. But India, the classic land of modern imperialist control, must continue under British tutelage. Meanwhile daily broadcasts from Tokyo, Bangkok, Rome, and Berlin in Hindustani announce that the Axis countries want India to be independent. Intelligent people know how false this is and are not taken in. But many who listen to this contrast it with what the British government says and does in India. We have seen the effect of this propaganda in Malaya and Burma. India is far more advanced politically and can therefore resist it more successfully. She is especially attracted to China and has admired the magnificent resistance of the Russian people. She feels friendly toward the democratic ideals of America. But with all that she feels helpless and frustrated and bitter against those who have put her in her present position.

Some of the problems are of our own making, some of British creation. But whoever may be responsible for them, we have to solve them. One of these problems, so often talked about, is the Hindu-Moslem problem. It is often forgotten that Moslems, like Hindus, also demand independence for India. Some of them (but only some) talk in terms of a separate state in the Northwest of India. They have never defined what they mean and few people take their demand seriously, especially in these days when small states have ceased to count and must inevitably be parts of a larger federation. The Hindu-Moslem problem will be solved in terms of federation, but it will be solved only when British interference with our affairs ceases. So long as there is a third party to intervene and encourage intransigent elements of either group, there will be no solution. A free India will face the problem in an entirely different setting and will, I have no doubt, solve it.

What do we want? A free, democratic, federal India, willing to be associated with other countries in larger federations. In particular, India would like to have close contacts with China and Soviet Russia, both her neighbors, and America. Every conceivable protection, guarantee, and help should be given our minority groups and those that are culturally or economically backward.

What should be done now? It is not an easy question, for what may be possible today becomes difficult tomorrow. What we might have done two years ago we have no time to do now. But this war is not going to end soon, and what happens in India is bound to make a great difference. The grand strategy of war requires an understanding of the urges that move people to action and sacrifice for a cause. It requires sacrifice not only of lives of brave men but of racial prejudices, of inherited conceptions of political or economic domination and exploitation of others, of vested interests of small groups that hinder the growth and development of others. It requires conception and translation into action, in so far as possible, of the new order based on the political and economic freedom of all countries, of world cooperation of free peoples, of revolutionary leadership along these lines, and of capacity to dare and face risks. What vested interests are we going to protect for years to come when the interests of humanity itself are at stake today? Where are the vested interests of Hong Kong and Singapore?

It is essential that whatever is to be done is done now. For it is the present that counts. What will happen after the war nobody knows, and to postpone anything till then is to admit bankruptcy and invite disaster.

I would suggest that the leaders of America and Britain declare: First, that every country is entitled to full freedom and to shape its own destiny, subject only to certain international requirements and their adjustment by international cooperation. Second, that this applies fully to countries at present within the British Empire, and that India’s independence is recognized as well as her right to frame her own constitution through an assembly of her elected representatives, who will also consider her future relations with Britain and other countries. Third, that all races and peoples must be treated as equal and allowed equal opportunities of growth and development. Individuals and races may and do differ, and some are culturally or intellectually more mature than others. But the door of advancement must be open to all; indeed those that are immature should receive every help and encouragement. Nothing has alienated people more from the Nazis than their racial theories and the brutal application of these theories. But a similar doctrine and its application are in constant evidence in subject countries.

Such a declaration dearly means the ending of imperialism everywhere with all its dominating position and special privileges. That will be a greater blow to Nazism and Fascism than any military triumph, for Nazism and Fascism are an intensification of the principle of imperialism. The issue of freedom will then be clean and clear before the world, and no subterfuge or equivocation will be possible.

ONLY A REAL CHANGE WILL INSPIRE THE PEOPLE

But the declaration, however good, is not enough, for no one believes in promises or is prepared to wait for the hereafter. Its translation into present and immediate practice will be the acid test. A full change-over may not be immediately possible, yet much can be done now. In India a change-over can take place without delay and without any complicated legal enactments. The British Parliament may pass laws in regard to it or it may not. We are not particularly interested, as we want to make our own laws in the future. A provisional national government could be formed and all real power transferred to it. This may be done even within the present structure, but it must be clearly understood that this structure will then be an unimportant covering for something that is entirely different. This national government will not be responsible to the British government or the Viceroy but to the people, though of course it will seek to cooperate with the British government and its agents. When opportunity offers in the future, further changes may take place through a constituent assembly. Meanwhile it may be possible to widen the basis of the present central assembly and make it a representative assembly to which the provisional national government will be responsible.

If this is done in the central government, it would not be at all difficult to make popular governments function in the provinces where no special changes are necessary and the apparatus for them exists already.

All this is possible without upsetting too suddenly the outer framework. But it involves a tremendous and vital change, and that is just what is needed from the point of view of striking popular imagination and gaining popular support. Only a real change-over and realization that the old system is dead past revival, that freedom has come, will galvanize the people into action. That freedom will come at a moment of dire peril and it will be terribly difficult for anyone to shoulder this tremendous responsibility. But whatever the dangers, they have to be faced and responsibility has to be shouldered.

The changes suggested would give India the status of an independent nation, but a peaceful change-over presumes mutual arrangements being made between representatives of India and Great Britain for governing their future relations. I do not think that the conception of wholly sovereign independent nations is compatible with world peace or progress. But we do not want international cooperation to be just a variation of the imperial theme with some dominant nations controlling international and national policies. The old idea of dominion status is unlikely to remain anywhere and it is peculiarly inapplicable to India. But India will welcome association with Britain and other countries, on an equal basis, as soon as all taint of imperialism is removed.

In immediate practice, after the independence of India is recognized, many old contacts will continue. The administrative machinery will largely remain, apart from individual cases, but it will be subject to such changes as will make it fit in with new conditions. The Indian Army must necessarily become a national army and cease to be looked upon as a mercenary army. Any future British military establishment would depend on many present and changing factors, chiefly the development of the war. It cannot continue as an alien army of occupation, as it has done in the past, but as an allied army its position would be different.

It is clear that if the changes suggested were made, India would line up completely with the countries fighting aggression. It is difficult, however, to prophesy what steps would be most effective at this particular juncture. If the military defence of India, now being carried on beyond her frontiers, proves ineffective, a new and difficult military situation arises that may require other measures. Mr. Gandhi, in common with others, has declared that we must resist aggression and not submit to any invader; but his methods of resistance, as is well known, are different. These peaceful methods seem odd in this world of brutal warfare. Yet, in certain circumstances, they may be the only alternative left us. The main thing is that we must not submit to aggression.

One thing is certain: whatever the outcome of this war, India is going to resist every attempt at domination, and a peace that has not solved the problem of India will not be of long purchase. Primarily this is Britain’s responsibility, but its consequences are worldwide and affect this war. No country can therefore ignore India’s present and her future, least of all America, on whom rests the vast burden of responsibility and toward whom so many millions look for right leadership at this crisis in world history.

Editor's Note: This article was reproduced with kind permission of Priyanka Gandhi Vadra in Fortune India's inaugural issue dated October 2010. The photographs don’t form part of the original article.