Lessons from Pakistan

With more than 400 schools worldwide, business is booming for the Lahore-based Beaconhouse group.

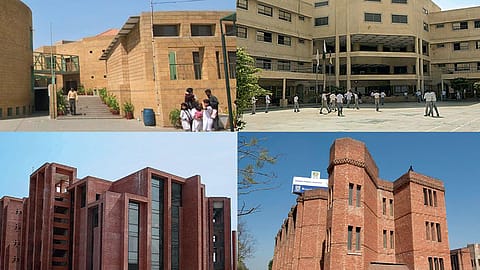

PAKISTAN is not the name that leaps to mind when one talks about multinational business or academics. And yet Lahore is home to one of the world’s largest networks of private schools—the Beaconhouse Group, which has more than 400 institutions and 195,000 students in nine countries. Its success could teach anyone in the education business a thing or two.

Beaconhouse’s growth was fostered by a combination of circumstances. As in parts of India, Pakistan’s government schools fail to inspire confidence in many parents. English-language education is seen as key to fulfilling aspirations. Groups such as Beaconhouse, The City School, and Roots School System, have filled a successful—and lucrative—niche in Pakistan and abroad.

Geraldine Seymour, international communications manager, University of Cambridge International Examinations (CIE), the world’s largest provider of international qualifications for 14-to-19-year-olds, says Pakistan is its biggest market with more than 460 affiliated schools. “The country also has the highest number of O Level entries in the world,” she adds. O Levels are secondary school exams that students take at age 16. Beaconhouse is among CIE’s largest clients.

Fortune India overcame dodgy phone lines to Lahore, eventually getting on Skype to chat with Beaconhouse Group chief executive Kasim Kasuri. He recalls that Beaconhouse was born in 1975, when his mother Nasreen Kasuri, now the group’s chairperson, searched in vain for a quality school for him and his brother. She started the Les Anges Montessori Academy in their home in Lahore. It was a success, and the family smelled a larger opportunity.

After Pakistan president Zia Ul-Haq reversed his predecessor Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s decision to nationalise education in 1978, Les Anges spread its wings, setting up schools in Islamabad and Karachi, and, over the next two decades, throughout Pakistan. Developing its own teaching staff was a differentiator for the group.

Kasuri plays down the suggestion that his family’s political clout—his father, Khurshid Mahmood Kasuri, was foreign minister under Musharraf between 2002 and 2007—helped the enterprise along. Beaconhouse has drawn flak for profiting from education—something frowned upon in Pakistan as it is here. Indian educationalist Shyama Chona, non-executive director of Educomp Solutions and a former principal of the Delhi Public School (DPS) network’s flagship school in R.K. Puram, New Delhi, notes that schools in the country must be set up through charitable societies or trusts. But many private ones get around this by offering allied services—selling books, providing uniforms, transport—that happen to be profitable. Educomp itself, a solutions provider that also runs preschools, is one of the few listed companies in India’s opaque private education sector. It reported a consolidated net profit of Rs 58 crore on revenue of Rs 277 crore in the second quarter of 2011.

Emphatic that he is not driven by profit alone, Kasuri describes Beaconhouse as a “socially responsible business”. He says: “Education is the state’s domain. But what if the state fails to deliver? With the private sector, there’s more accountability. Economies of scale have let us offer more within a relatively reasonable fee structure.”

Seeing an opportunity in quality education for the middle class—and possibly to counter the elitist tag—Beaconhouse opened a second set of schools, called The Educators, with funding from the International Finance Corporation, the private lending arm of the World Bank. The company took the franchise route, with schools being affiliated to the Pakistan education board. The average fee in The Educators is about 1,500 Pakistani rupees (Rs 792) a month—a fifth of the Beaconhouse average. The Educators has 105,000 students in nearly 250 schools, says Kasuri.

(INR CR)

In 2004, the group went global by acquiring a school in Malaysia. Now it has 18 schools and nearly 10,000 students outside Pakistan. It also started a third set of schools in Pakistan—the ultra-premium TNS Beaconhouse schools, which don’t follow a conventional exam-oriented curriculum—and the Beaconhouse National University in Lahore.

The company is mum on revenue numbers, saying it needs to keep a low profile as it is vulnerable to criticism of profiteering from education. But the numbers are impressive enough to attract private equity: Seven PE firms offered to fund global expansion plans in 2008. Finally, the New York-based New Silk Route (NSR) invested an undisclosed amount in exchange for a minority stake. Dubai-based NSR partner Jens Yahya Zimmermann says the prospects of education in emerging markets are investment-worthy. “Even in risky markets, education is rarely affected, especially for well-run institutions with a proven track record.” It couldn’t have hurt that Abdul Hafeez Shaikh, then a general partner at NSR and now finance minister of Pakistan, was a friend of the Kasuri family.

Beaconhouse plans to push further into Bangladesh, Southeast Asia, and East Africa. Kasuri sees the share of international revenue rising to 50% from the current 20% in the next five years. “The number isn’t as daunting as it seems. The annual fee for our boarding school in England is £22,000 (Rs 15.45 lakh). That’s several times what we charge in Pakistan,” he says.

Indian firms could take a leaf from Beaconhouse’s book in terms of scale and ambition. Private schools such as DPS and Modern School are thriving, but there’s opportunity to do more. Ashish Rajpal, chief executive of iDiscoveri, a company that works with schools to improve curricula, says: “India has 300 million children who should be in good schools. Something like The Educators is waiting to happen here. Many one-acre schools with up to Rs 2 crore in capital expenditure can make a profit.”

Kasuri shares this view. He says the brand equity built up over the years by many Indian schools can be leveraged to generate profits abroad, which can then be used to widen their networks in India. “One could say that’s an incentive for Indian private schools to seek new markets, where they don’t face the restrictions they do in India.” His advice to Indian schools looking

to set up shop abroad: Acquire existing schools, and look beyond the Indian diaspora.

Some educators disagree. Ashok Chandra, chairman of the DPS Society, which runs more than 160 schools, says his group’s schools abroad cater to parents who want their kids educated according to the Indian curriculum of the CBSE or ICSE boards.

Perspectives may differ, but one thing is clear: Beaconhouse certainly knows how to mind its business and earn a little bit of neighbour’s envy.