Living in the new normal

ADVERTISEMENT

WHEN THE CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER at the world’s sixth-largest steel company says “the uncertainty factor has gone up considerably”, it’s a sign that India Inc. is worried. Koushik Chatterjee, CFO of Tata Steel, goes on: Government apathy, uncertainty on the regulatory front, and environmental issues are just some of the factors that add pain to the economic slowdown.

“Today there is a host of stakeholders that you need to engage and explain what the outcome of the project will be, what its impact will be on society, people, and the community at large,” he says. All this adds to the time taken to complete a project: “Earlier we believed we could commission a plant in four years, but now it is difficult to say how long it will take.”

Chatterjee says Tata Steel managers build up to seven scenarios for every project; even a year ago, they took a decision based on just a couple. “We have to work out different scenarios depending on different triggers. For instance, if I don’t get land, what do I do? What happens if there are regulatory changes?”

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

The entire process, he says, has become far more difficult and time-consuming. But no company can afford huge delays when implementing projects; to save time, Tata Steel has started executing projects sequentially, and allocating capital in phases. “For instance, when land acquisition happens, some funds will be raised to take the project to the next step,” explains Chatterjee. “Only after we have the necessary clearances and have invested 15% to 20% of our own equity do we approach financial institutions for funding.”

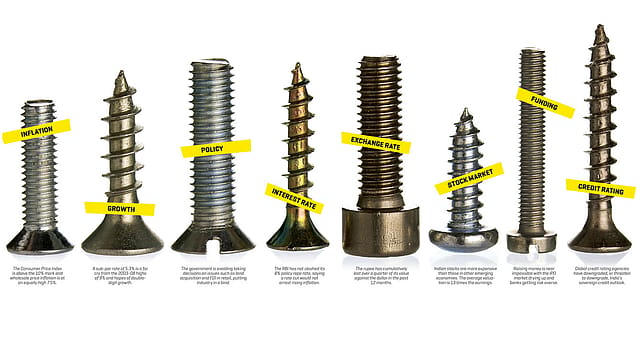

Tata Steel’s problems are not unique. The current slowdown, worsened by regulatory uncertainty, has affected most companies similarly. McKinsey & Co.’s India head Adil Zainulbhai says he’s begun advising clients to expand in a phased manner. “If you think you need 1 million sq. ft. of space over the next few years, instead of acquiring all 1 million in one go, break it up and buy, say, 20,000 sq. ft. to start with.” The underlying assumption which he doesn’t spell out is that the company may never need 1 million sq. ft. Economic growth has fallen to an all-time low of 5.3% in the January-March quarter of this year; industrial production growth fell to -3.2% in March and rose fractionally to 0.1% in April; and foreign direct investment fell by 41% in April compared with the same period last year.

Reality check: By developed economy standards, some of these stats aren’t to be sniffed at. And, low growth and production are not really new. Till the early 1980s, India grew at an average of 3.5%. It inched ahead a bit thereafter. The picture changed dramatically after the economy was liberalised, culminating in the 9% era between 2003 and 2008. India was the toast of the world, on track to become the world’s third-largest economy in a few decades. The question on many lips: Was that a false dawn? Jagannadham Thunuguntla, strategist and head of research at SMC Global Securities, says the boom years were an aberration because of a convergence of factors which is unlikely to be repeated. “The India growth story is over,” he says categorically.

“The worst current account deficit in two decades, widening fiscal deficit, sliding rupee, and high inflation are only the symptoms and not the cause of India’s economic woes. They merely reflect the lack of governance, fractured politics, and a weak investment climate,” says Subodh Narain Agrawal, chairman of London-based Euromax Capital, an investment banking firm.

The inability of Eurozone investors to finance the Indian capital market because of increased risk aversion and pressure from European banks to deleverage means less capital inflows into the Indian stock market and a continued pressure on the current account deficit. American investors are equally skittish. Moreover, unlike 2008-09, the government does not have the necessary firepower to inject fiscal stimulus to rev up the slowing economy. What compounds the problem is that many have lost faith in the government and believe it’s part of the problem. As Vinayak Chatterjee, chairman, Feedback Infrastructure Services, an infrastructure consultancy firm, says: “It is all about leadership, and there is no real leadership in the country.”

According to a Citi Equities report, the number of stalled projects has been rising steadily. As of March 2012, the total cost of stalled projects was Rs 7.57 lakh crore, a 91% jump over the same period last year. “Nearly 77% of stalled projects belong to the private sector and is the highest since 1995, the first year from which data is available. It is even higher than in 2003 [after a multi-year slowdown in capex and before the start of the latest capex cycle].”

The predominant note in India Inc. is one of despair. Sanjay Nayar, CEO, India operations of private equity fund Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR) estimates that companies that grew at an average of 20% a year will now grow at 12%. That’s a huge fall and the results of such a slowdown will be felt for far longer.

Most of the companies KKR has invested in, including Bharti Infratel and Dalmia Cement, are growing at 15% lower than estimated margins due to a combined high inflation rate and what Nayar calls the “price elasticity of goods”—people will only pay up to a certain amount. Profits too have been hit. “Unless growth takes off and sentiments change, Indian businessmen will not need money, and if they don’t need money, there’s very little a PE fund can do.”

The trouble is, seduced by the go-go years, Indian companies built plans which assumed higher growth rates, a cheaper rupee, booming stock markets, lower inflation, etc. Those plans are now in disarray. David Cornell, who runs the $80 million (Rs 456.1 crore) India portfolio of specialist investor Ocean Dial, says India Inc. has no choice but to get used to subpar growth. “India is in the grip of a vicious cycle where high capital costs defer investment decisions and the lack of investments pushes up inflation.”

Resetting expectations isn’t easy. M.S. Unnikrishnan, managing director of Thermax, an engineering solutions company, says: “For the next two to four years, our GDP could be as low as 5% to 6.5%. Till 2015, we have to think of consolidation.” Many are pulling back from risky businesses, others are hoping short-term cost-cutting measures will do the trick.

This very caution could be to blame for some of India Inc.’s woes, says marketing consultant Rama Bijapurkar. “If there is a new normal, it has been caused by Indian businesses holding back rather than scrambling to react to global forces,” she says. In this, she echoes Zainulbhai, who says he has noticed that for a year or more now, businesses have been reluctant to invest.

M.V.S. Seshagiri Rao, group CFO, JSW Group, says in troubled times companies should sit on cash rather than make risky investments. For JSW, cash is definitely king today. “We used to have a working capital of around Rs 1,500 crore to Rs 2,000 crore, and cash balances of about Rs 500 crore. Now the cash balances have gone up to between Rs 2,500 crore and Rs 3,000 crore and working capital has come down.”

Nayar says he is making sure that KKR goes the extra mile to help companies through these difficult times. “It means cutting costs, improving inventory management, and finding new markets, and helping them with capital restructuring.” By all accounts, KKR may also postpone some exits; Nayar says some clients have been advised “to wait for two years before listing”, given that the market is narrow, shallow, and not conducive to new companies.

Cornell agrees that the equity market is not a happy place at this point, despite valuations of Indian stocks being lower; they trade at an average of 13 times the current price-earnings ratio. “Even at these valuations, Indian stocks are still more expensive than those of Brazil, Russia, China, and Peru. Returns on assets too have come down from the high of 14% in 2007 to less than 10% now.” What this also means is that companies are finding it difficult to raise funds by offloading a part of their equity in today’s market. While valuations may seem low, few buyers think they are fair.

Companies in infrastructure are finding it increasingly difficult to raise working capital or funding for future expansion. Banks already have a high level of non-performing assets, and are unwilling to lend more; PE players who invested heavily in the boom of 2003-04 are now extremely cautious about choosing potential investments.

There’s also the problem of the volatile currency, with the rupee recently touching an all-time low of Rs 57 to a dollar. “If the rupee fluctuates between, say, Rs 55 and Rs 60 against the dollar, I can hedge against it. But now the feeling is that it could fluctuate anywhere between Rs 41 and Rs 60—no one can hedge this,” says Zainulbhai. Instead, he advises clients to look for natural hedges. “These could be extensions to your core product that can swiftly increase revenue and derive revenue from places ignored thus far. Plan a natural hedge of at least 30%,” he says.

WITH NO CLEAR POLICY OR ECONOMIC guidelines in place, multinationals are getting uneasy. According to a recent report by the Nomura Research Institute, foreign investors are pulling money out of India at an accelerating rate, moving $10.7 billion out of the country in 2011, up from $7.2 billion in 2010. Foreign companies too are following suit. New York Life sold its 26% stake in its insurance venture with Max India for $530 million, while U.S. mutual funds giant Fidelity Worldwide Investment recently struck a deal to sell its Indian subsidiary to L&T Finance.

It’s not just foreign money that’s leaving the country. Indian companies with cash to invest are looking at overseas destinations. “Our investments abroad will continue—like buying a plant either in Poland or Hungary and another in Brazil,” says Omkar Singh Kanwar, chairman, Apollo Tyres. Kanwar says it’s getting difficult for his company to do business in India; the extremely high cost of natural rubber, coupled with the inverted duty structure, makes manufacturing here very expensive. Companies have to pay 10% duty when importing rubber tyres, but 20% when importing rubber. “While the government says it understands our plight, there’s been no real action,” says Kanwar, adding that this is why Apollo will be making greater investments outside India.

Indian money is going abroad in another way as well. Smaller companies are actively considering shifting base to Thailand, where interest rates are low (3.5% compared with 11% here) and power is plentiful and cheap. The tax rates are often lower, and the currency less volatile than the rupee. “Indian firms will have to shift base to remain competitive in today’s market,” says Arvind Kapur, president of the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association of India.

Kapur, who is also managing director of auto components maker Rico Auto Industries, says he has put all his expansion plans on hold. He had planned to double capacity to meet the future demands of car makers. The high capital cost of such an expansion would have been met by demand from auto companies, which had then announced expansion plans. But now that car manufacturers have shelved their plans, Kapur has been forced to do the same. Since he had not started raising funds for the expansion, he hasn’t suffered a financial loss or had to lay off excess manpower, but growth has been hit.

Baba N. Kalyani, chairman and managing director of Bharat Forge, a leading auto components maker, is also closing the tap on any new capital investment programme. “Given the uncertainty in the business environment, we won’t make any new capital expenditure in FY13. We will just take a holiday,” he says.

Other auto parts companies are shifting focus to more profitable avenues. For instance, the Rs 1,000 crore Shriram Pistons and Rings is moving away from the heavy commercial vehicles space, where sales are falling, to the growing sector of smaller commercial vehicles and tractors. The company’s MD, A.K. Taneja, says while the company is not cutting spending on design, development, maintenance, and safety, it is reducing expenditure on office renovation; recruitment is also on hold. The company is also focussing more on the replacement market, which, Taneja says, “is far less volatile than car sales”.

“The despondency is far greater today among the auto component manufacturers than in 2008-09 because most of us have realised that we are our worst enemies,” says Taneja. In 2008, the industry was caught unaware by American car makers slashing production. Exports, which were key to the Indian industry, took a beating. This time, however, the problems are domestic, he says.

The government’s ambivalence on freeing diesel prices has thrown auto component manufacturers’ plans into chaos. They are left wondering whether or not to invest in production lines for diesel cars, which are outselling petrol cars because of the difference in the cost of the fuels. “Most of us are holding on to our investments because the diesel policy has become like a game of tennis between the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas and the Ministry of Heavy Industries,” says Taneja.

With the government washing its hands of contentious issues such as land acquisition, coal and gas linkages, and other execution problems, infrastructure players, who were invited by the government to set up projects, also find themselves in a bind. Amitabh Mundra, director, Simplex Infrastructures, which provides services to infrastructure firms, maintains that his company has become far more cautious while bidding for projects, and is more choosy about clients because cash management has become top priority. It seeks clients that have a strong balance sheet so that payment is not deferred. With Rs 2,000 crore of debt, Simplex’s balance sheet is already stretched, and the company needs capital to invest in future projects.

Thermax is also being cautious, while not going entirely into safe mode. “Only some immediate expenses are being curtailed. We are holding back on a line-balancing project for next year, but going ahead with a greenfield project for an air pollution factory,” says Thermax’s Unnikrishnan.

Power is another problem area, with the government under pressure from political allies to maintain tariffs at the present level. The combined financial losses of all power distribution companies today is estimated at a staggering Rs 1.2 lakh crore, up from Rs 21,000 crore in 2005-06, because of the rising gap between the cost of supply and realisation. Distribution companies are losing Rs 2 per unit of power sold. And unless the government raises power tariffs substantially, companies will continue to bleed. At the time of going to press, the tariff for commercial customers in Delhi was raised by 19.5%; power companies say if they are to stop making such losses, the hike needs to be at least 60%.

This has implications for other industries. For power equipment manufacturers, it has meant the drying up of fresh orders and for companies across the value chain, implementation milestones have gone haywire. These developments have had a huge impact on their cash cycles and their ability to raise more funds through invoices.

Real estate companies are also deep in debt—often because of stalled projects, but now also because of demand slowing. Anshul Jain, CEO, India, DTZ, an international property advisory, says realty firms that overleveraged their balance sheets during the boom period are now looking at ways to reduce their debt. “DLF, which is sitting on Rs 20,000 crore of debt, has already made it clear that it will be selling off non-core assets such as hotels and shedding manpower to reduce its debt liabilities,” he adds. DLF could not be reached for comment.

WHAT INDUSTRY WANTS IS FOR the United Progressive Alliance-led government to get the economy back on track by opening FDI in retail, insurance, and pensions; passing critical bills such as the land acquisition bill and the Companies Bill that are holding up business; providing consistent policies to ensure that development is not hindered; and other similar pro-industry steps.

Apollo’s Kanwar says: “It is not that the government is unwilling to take decisions, but every time it tries to do so, it is held hostage. The government seems incapable of managing the pulls and pressures of coalition politics.”

Unsure of how much to rely on external factors companies are looking inwards for ways in which to weather the crisis. They are not ignoring the most obvious—cost-cutting and hiring freezes. According to Aon Hewitt’s annual salary increase survey for 2012, there’s likely to be a marginal fall in the level of hikes. The global human resources consultancy estimates salary increases for India at 11.9% in 2012, lower than the 12.6% increase in 2011. “The number mirrors a positive, yet cautious, outlook as organisations strive to take a balanced view in light of the uncertain economic environment,” the survey mentioned.

“We are currently focussed on generating more from our existing resources, be it material or manpower resources. Recruitment is strictly on a need basis. We are trying to extract the maximum juice,” says Vijay Shankar Sharma, CEO, Orient Bell, a ceramic tiles maker. Mundra of Simplex echoes this when he says all hiring has been put on hold.

Other companies are trying to raise money by selling off assets. Lanco Infratech, for instance, has already decided to sell its hydropower generation business, because it has a debt of Rs 28,036 crore as on March 31, 2012, an increase of around 90% from

Rs 14,679 crore in 2011-12. High fuel costs, low capacity utilisation of its power plants, and higher interest rates dragged the company into losses—Rs 112 crore in FY12.

In all this, there are still some optimists such as Adi Godrej, chairman, Godrej Industries. “This too shall pass,” he says, philosophically, when asked about the downturn. “We are confident that in the next decade, India will grow at an average of 9%.” The company has no plans to defer its investments, and Godrej adds that even now, well-managed groups should have no trouble raising money.

Other companies are looking for cheap investments. “During a downturn, many less efficient companies close down or suffer substantial losses. This is the time to acquire companies to extend market share,” says Orient Bell’s Sharma. The company has done this in the past; in the 2010 slowdown, the company, then called Orient Ceramics, bought the loss-making Bell Ceramics for Rs 16 crore. Today, the combined entity is one of the largest tile makers in the country.

N.R. Narayana Murthy, chairman emeritus, Infosys, is also looking at the silver lining. This is the time when Indian industry and government can become efficient, he says. “The age of ‘even if we do nothing we will grow and get customers’ is over. This is the time to clean up the system. This is the time to root out inefficiencies. And the new normal should be a leaner, cleaner ecosystem.”

Other positive voices come from sectors that aren’t feeling the immediate impact of the slowdown, notably consumer goods and retail. The effects of the slowdown are yet to be felt by these sectors and so it’s business as usual for them. “At the moment, we see no reason for revising either our budgets or our growth projections,” says Harsh Mariwala of consumer goods company Marico. Only a major catastrophe, such as a poor monsoon which will hurt rural demand, will make the company change its existing plan, he adds.

Ashish Garg, MD, Promart Retail, a company that runs a chain of retail stores across India, is also upbeat. “We are planning to grow from eight stores to 100 in the next couple of years and see no need to revise our target of growing from revenues of Rs 70 crore a year to Rs 450 crore.” Garg is confident because the company plans to expand in semi-urban and rural markets, where the cost of setting up stores is lower than in a metro. “We see no real impact on those markets to make us revise our targets,” he says. Also, he adds, those areas are underserved, and so there’s enough demand to ensure a decent return on investment; the same is not true of a metro.

CEO of Future Brands, Santosh Desai, explains where such optimism is coming from. He says there’s a fundamental shift in the consumer mindset of semi-urban and rural India. “An economist might not necessarily have the tools to understand this optimism. You need sociological tools,” says Desai. “People in villages and smaller towns are brimming with self expression. They were always driven by samaaj or community, but are now moved by samay or the times. Hence, the urge to appear modern. This means a demand for relevant brands for millions of people, many of whom are part of a cash economy and not necessarily the measured economy. There will be furious demand here as people seek to redefine their identity by spending money.”

Garg echoes this: “Our core business is clothes and we see a major untapped demand that will not fall.”

But such optimists are far scarcer than those who believe the sky is falling. The truth, as always, lies somewhere between the two opposites. What’s important are the lessons to be learnt from this downturn. When Jeremy Grantham, chairman of global investment management firm GMO, was asked whether anything would be learned from this turmoil, he replied, “We will learn an enormous amount in the very short term, quite a bit in the medium term and absolutely nothing in the long term. That is the historical precedent.”

What lies ahead

The Planning Commission, led by Arun Maira, former India head of the Boston Consulting Group, has created a set of scenarios and how India’s growth will pan out. Fortune India was given a first look at these scenarios, which are called Muddling Along, Falling Apart, and the Flotilla Advances.

The work takes forward a scenario-planning exercise led by Maira in association with the World Economic Forum and the World Bank in 2005 and 2007, which showed the scenario between 2015 and 2025. Many of the ideas presented in these scenarios have come true in the India of 2012, says Maira.

According to the new scenarios, the normal for business will be determined as much by the price of raw materials and demand as by statistics; the economic climate will be determined by the ecosystem and not merely GDP numbers.

India is currently ‘muddling along’ and is at a fork where it will either fall apart or there will be a ‘flotilla advances’ model of

growth with a strong focus on community solutions and community leadership. In this model, the state has a limited role; it hands over resources to communities, which will then have to fix solutions for themselves.

But till that happens, it is up to the government to take some steps to change investor sentiment. A good start will be allowing FDI in the retail and aviation sectors, increasing foreign equity in the insurance sector to 49%, and implementing the general goods and services tax (GST) and the National Manufacturing Policy. “GST alone will add 1.5% to 2% to the GDP,’’ says Adi Godrej, chairman, Godrej Group.

Over the longer term, the government needs to make larger investments and remove bottlenecks such as coal and gas linkages, issues of land acquisition, and environmental and other regulatory issues that stymie infrastructure development. But, as is becoming increasingly evident, that is the biggest if.