The future's not ours to see

ADVERTISEMENT

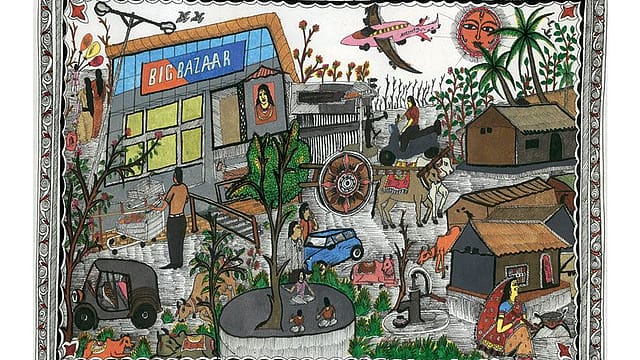

WALKING INTO THE BIG BAZAAR OUTLET in Gurgaon’s Sahara Mall is like entering chaos. Packets of the store’s own brand of biscuits, Tasty Treat, are tumbled together in a large box with Britannia’s Tiger biscuits, along with packets of chips and other snack foods. Mops, pots, sponges, and plastic bottles jostle for space on a nearby table. The aisles are narrow and there’s barely space to squeeze a cart through. We hope to pick up a couple of soft drinks, but can’t find a beverages section. It’s almost like going to Delhi’s crowded Lajpat Nagar market or Kolkata’s Gariahat—minus the heat and dust. And that’s precisely what Kishore Biyani, CEO of the Future Group was looking to replicate when he set up the Big Bazaar chain.

Biyani’s theory that “Indians feel at home in the chaos of a market” has its share of critics. “The best practices in retail design are global. The idea that Indian consumers can’t bridge the gap between a marketplace experience and organised retail experience is patronising at best,” says David Blair, Fitch Design’s managing director in India, whose company has designed retail stores such as the Aditya Birla Group’s chain, More.

Critics or not, Biyani is still convinced of the theory. However, he is shrewd enough to understand that consumers are evolving, and he has created a store for those who want a more organised shopping experience. The Big Bazaar Family Center in a posh mall in Vasant Kunj, New Delhi, for example, has been designed along the lines of international retail stores, with wide, well-lit aisles, and rows of products that are stacked, not heaped. So far, there are only five such (Big Bazaar operates 135 stores in total), but more might be set up depending on customer response.

It’s near impossible to get Biyani to comment on the changing face of Big Bazaar. Sitting in his new corporate office in Vikhroli, a Mumbai suburb, he’s constantly fidgeting, answering the phone, and otherwise easily distracted. But ask him about his next big bet—consumer goods—and his eyes light up and he’s fully focussed. “I want to be one of the top five companies in the fast-moving consumer goods space in the next five years,” he says. In the process, he plans to transform the $3 billion (Rs 13,479 crore) Future Group to a $20 billion company with 43 million square feet of retail space and a presence in 110 cities by 2020.

The idea seems simple enough: Big Bazaar has a wide range of in-store or private labels, which Biyani wants to make available even at neighbourhood kirana stores. But there’s a world of difference between pushing private labels in your own location and getting small shops to stock and promote them. Biyani’s up against stiff competition. Companies such as Hindustan Unilever and ITC have been in the business of manufacturing and distributing fast-moving consumer goods for decades, and their distribution networks are the stuff of marketing legend.

“We understand Indian consumers and their consumption habits better than most others. Over the years, we have tried to reach different customers through various formats and succeeded,” says Biyani, when asked how he plans to take on established giants including P&G, Nestlé, and Reckitt Benckiser.

But that’s not going to be enough for Biyani to be able to get his jams, sauces, biscuits, and toothbrushes on the shelves of kirana stores across the country. “Just having your own private labels does not necessarily mean that you become a consumer goods player. Because you have a captive audience coming to your retail chains, you might be able to sell your private labels, but not necessarily overtake other established brands,” says Sunil Alagh, managing director and CEO of Britannia Industries from 1989 to 2003, and now chairman of consultancy firm SKA Advisors.

Biyani differs. His surprise plan: buy more distribution. He wants to pick up established small- and medium-sized consumer goods outfits, and then leverage their reach to get his own products into far-flung shops. He’s also planning some smart tie-ups that will give him the same advantage. He’s already begun that; the Future Group’s tie-up with Capital Foods, which has brands such as Smith & Jones, means that Future Group labels can be sold in the 3.5 lakh stores where Capital Foods is distributed. “We want to go deeper and wider in distribution,” adds Biyani.

He’s getting the logistics ready for this. “We are, perhaps, the only company that runs its own fleet of 800 trucks across 85 cities and 60 rural locations and 4 million square feet of warehousing space,” says Anshuman Singh, CEO, Future Logistics.

BIYANI IS OPTIMISTIC THAT there will be a demand for his products. He’s basing this on the fact that his private brands in the consumer goods segment, from the Tasty Treat brand of instant soups to Sach toothbrushes and toothpastes (Sachin Tendulkar lent his name to the brand), saw a 75% increase in sales in the last one year. The number of private labels has also gone up. “We have private brands in 58 categories with over 300 items and these enjoy between 8% and 35% share of sales in their respective categories. And with 185 Food Bazaar stores, 123 KB Fairprice outlets and one FoodRight store in Mumbai, the company’s reach and scale is now unparalleled in the market,” Biyani says with pride. Private labels, on average, provide 25% to 30% higher margins than those offered by the big brands. In consumer products, these margins can be as high as 40% compared with 12% to 17% for brands.

So can the Future Group’s present success with private labels propel Biyani’s consumer goods play? “Yes, you will make profits (or increase your margins) through the sale of private labels,” says a Delhi-based retail analyst. “But to do that, you don’t need to become a consumer goods player. Wal-Mart has a 40% share of private labels, Marks & Spencer has 99.9% share of private labels but that doesn’t mean that they are consumer goods players. They are all retailers.”

One of the main reasons for that is that globally, organised retail dictates margins. In India, however, the consumer goods manufacturers dictate margins; organised retail accounts for barely 8% of sales, and the majority is sold through small, unorganised, neighbourhood kirana stores. Companies that manufacture a wide range of goods, often use sheer muscle power to get the small stores to prominently display and push their brands. Shopkeepers regularly allege that large consumer goods companies threaten to withhold supply of fast moving products to shops that don’t stock and display their other products. Biyani does not have any such lever yet.

WHAT HE'S BANKING ON, instead, is insight. Future Group’s everyday conversations with customers has given it an unparalleled knowledge of what middle India is seeking. “It is the first retail player that has understood the growing crisis of identity among ethnic communities, especially the migrant population, and catered to their needs,” says Tejaswani Adhikari, chief insights officer, Future Group. That includes offering specific rice varieties, such as gobindabhog to Bengalis, and sona masoori to Maharashtrians. “We will create products that are ethnically relevant. I can create products for the ethnic communities in Bangalore that will be very different from the ones I produce for the people of Delhi. How many consumer goods players can do that?” asks Sanjay Jog, chief people’s officer, Future Group.

“Our objective has always been to understand the customer in the context of the community and not as an individual. And in the process we are building, nurturing and supporting the community,” says Biyani. He encourages initiatives that are based on watching customer behaviour or listening to their demands—a responsibility that the Future Group top managers leave to the store managers. “Since we realised that our store managers are the best judge of customer behaviour, we have given them the freedom to carry out such plans,” says Jog. It was a store manager who suggested that the in-store oral care brand, Sach, be packaged in a traveller-friendly manner. Big Bazaar began offering Sach kits, which contained a toothbrush, toothpaste, and a small towel. The kits were a roaring success. Another store manager realised that most customers did not use soup bowls for soup; he suggested that free cups be offered with the in-store instant soup brand, Tasty Treat. “As customers change, we too will have to change to capture consumption,” says Jog.

Alagh, however, does not think this aspect will make a huge difference to Biyani’s ambition to be a force in the fast-moving consumer goods sector. “The whole ethnic business—producing stuff that caters to a certain community—is only applicable in the case of foods but not in other categories,” he says. “If they [Future Group] can produce something which tastes unique and is priced lower than their competitors, they can be a force to reckon with.” But when it comes to soaps, detergents, and shampoos, the group might not be in the running at all, he adds. “Making value additions in commodities is not that easy. Many people have tried it without much success.”

Unlike consumer goods companies such as Hindustan Unilever or Britannia, which manufacture many of the products they sell, the Future Group will rely on third-party manufacturers in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. This is how most retailers in India source products that are then branded with the store’s own label. “When you have third-party manufacturers, there is very little scope for financial arbitrage, so even playing the competitive price game will not be easy, because third-party manufacturers rarely give discounts,” says an analyst who does not want to be named.

THERE'S ALSO THE NEW PROBLEM of rising prices in China. When Fortune India met Biyani a few weeks ago, he had just been told that for the first time in 30 years, the prices of non-food manufactured goods in China were going up. Like many retail players in India, Future Group sources at least 10% to 12% of its goods from China, so a price rise there is bad news. There’s no indication of whether prices will come down, so the group will have to learn to live with what Biyani calls a “new normal of higher prices”.

“The introduction of the cash-and-carry system will see a paradigm shift in the way sourcing is done in the country and we will be the first to benefit from it because we do not carry any added legacy,” says Damodar Mall, director, food strategy, at Future Group. But experts say that this is not entirely logical. “If a Future Group can do it, why can’t a Wal-Mart or a Metro do so, and far more efficiently?” asks a Delhi-based analyst. “After all, these global retail chains have a global sourcing strategy and can source far cheaper than others. For instance, they can afford to buy stuff cheaper from Thailand and can get huge discounts from China because they buy in such huge quantities.”

In most of the Big Bazaar outlets, store brands are prominently displayed—and are almost always cheaper than comparative branded products. Even when the price is not significantly lower, the shop offers freebies to make up. For example, 950 g of Fresh and Pure tea (an in-store brand) costs Rs 279, while the same weight of Brooke Bond’s Red Label tea costs Rs 275. But Big Bazaar offers 2 kg of sugar (worth Rs 60) free with its own brand, while Red Label comes with Rs 25 worth of jam free.

This is not something the group can do outside of its own stores. Fortune India asked some of the key members of Biyani’s team (almost all of them have some experience in other large consumer goods companies) what they thought would be the key differentiator. Value-addition, is the almost unanimous answer.

“I would rather sell rice at Rs 40 a kilo through value-additions than sell at Rs 20 and save Rs 2 through better supply chain management,” says Mall. The focus of Future Group will be on sourcing better quality products (not necessarily cheaper) and packaging them better, so buyers are willing to pay extra, he adds.

“Never underestimate our ability to craft a brand that is comparable to that of any other consumer goods player. For every brand, we will do customer insight mining, debate and discuss the idea of the brand, and use the services of the best advertising agencies,” says Mall.

What about brand promotions and advertising? So far, like other retailers with private brands (notably retail chain Spencer’s), all private non-apparel brands are promoted (or celebrated) within the store. “Instead of celebrating a brand on national television like other consumer goods companies, we celebrate the brands in our stores itself. So I can have a far more focussed approached on the brand,” says Jog.

He adds that the products will only sell if the customer likes them, otherwise no amount of in-store celebrations will help. Biyani is also clear that since his first duty is towards his customers, not stakeholders, he will never reduce the choice before his customers by pushing his own private brands. “That’s just not our strategy,” he adds.

An ambitious strategy alone is not likely to get the Future Group’s consumer goods business going. Biyani plans to use the proceeds of the recent Future Venture initial public offering (around Rs 750 crore) to fund his grand plan. But the IPO met with tepid interest, and was oversubscribed a mere 1.5 times.

There are other money problems that worry analysts who track this sector. The company’s turnover (according to its balance sheet of 2009-10) is Rs 13,000 crore, and it has debt of Rs 10,000 crore. As the retail analyst says, that’s not a happy position to be in.

Pantaloon Retail, one of the Future Group’s listed companies, shows that interest payments and finance charges at Rs 288.2 crore are actually higher than its profit before taxes and exceptional items of Rs 226.6 crore. Interest payments account for close to 21% of the company’s total debt of Rs 1,386.2 crore. Company finance experts say that this is worryingly high.

Pantaloon is trading at around Rs 262, a fall from its high of Rs 2,378 in 2006. The other listed venture, Future Capital Holdings, is doing no better, languishing around Rs 145 compared to the high of Rs 1,190 it touched soon after listing in 2008.

Biyani, however, pays no heed to the sceptics. “Our debt is just around Rs 3,500 crore and we have a debt equity ratio of 1:1. So, financing our mega plans will not be a constraint.”

A New Delhi-based retail analyst adds that the Future Group’s retail muscle is overstated. “Biyani’s total organised retail business is between Rs 12,000 crore and Rs 13,000 crore (or approximately $3 billion), while the total size of the retail business in the country—that is, consumer retail spending—is $500 billion to $600 billion.”

Fortune India had caught Biyani on a bad day. He had just returned from Chennai, from the funeral of his board member and CEO of Future Value Retail, Raghu Pillai, 54. But even as he struggled to come to terms with the untimely death of a colleague and an industry veteran, his optimism was irrepressible. So, would he like to be considered the king of retail in India? “You can call me the next raja of consumer goods,” he says, with a twinkle in his eye.