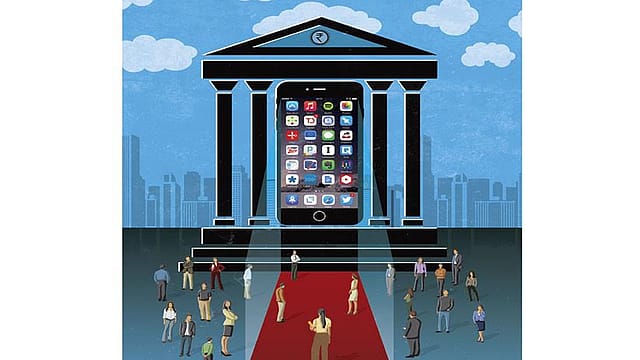

Banking: The future is in apps

ADVERTISEMENT

In an upmarket Mumbai locality, a colleague has just opened a savings account at DBS Bank; it’s a “digibank”, he explains, when we seek details. At a visit to a Café Coffee Day outlet, he saw a sign announcing that the coffee shop was a DBS Bank “branch”. Intrigued, he did some research, and in a few hours had opened a zero-balance account. The account offered 7% interest and an unmetered debit card. The digibank operates on an app; some 500 Cafe Coffee Day outlets have been given fingerprint scanners so customers can validate their accounts using Aadhaar (the unique identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India, UIDAI) and biometrics.

Meanwhile, in rural Karnataka, a labourer walks into a local kirana store, and deposits a few hundred rupees into his savings account. The shopkeeper has a smartphone and a small fingerprint scanner, and the farmhand uses his Aadhaar number and fingerprint to authenticate his account. The shopkeeper uses an app developed by Novopay Solutions, which is the interface for four banks—Bank of India, Axis Bank, RBL Bank, and IDFC Bank.

The Novopay core banking system allows it to offer services such as payments, savings accounts, and loans. For the banks, it makes sense to go with Novopay, since there’s no need to invest in any kind of infrastructure in rural India. Many of these banks have invested heavily in technology, particularly mobile, to take their services to a greater number. However, Novopay addresses the section that still does not have sufficient digital or banking literacy to afford or use these apps; all it needs is for one person to be taught how to use the app.

January 2026

Netflix, which has been in India for a decade, has successfully struck a balance between high-class premium content and pricing that attracts a range of customers. Find out how the U.S. streaming giant evolved in India, plus an exclusive interview with CEO Ted Sarandos. Also read about the Best Investments for 2026, and how rising growth and easing inflation will come in handy for finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares Budget 2026.

WELCOME TO RETAIL banking today, when a smartphone app and a fingerprint take the place of a passbook and a chequebook, while a touchscreen and a fingerprint scanner serves as a bank branch. With easy access to developers and technology, getting an app made isn’t difficult. All the banks we spoke to (public and private sector) have or are planning to launch apps for a similar set of functions—a ‘mother’ or central app, payments, wallet, social banking with Facebook/Twitter/Whatsapp integration, and apps for lending.

It’s almost like the computerisation fever that gripped the banking industry in the 1990s, when every bank worth its teller had “computerised branches” and there were regular news reports on how many branches the mammoth State Bank of India had computerised. Today, those banks offer apps, and the difference is in what those apps do.

“There is increasing pressure in terms of customer experience, not just from our peer bank platforms, but from the kind of customer experiences that Google, or Amazon, or Uber were able to create,” says Rajiv Anand, president, retail banking, Axis Bank. The lender, which has chosen to invest in more automated teller machines (ATMs) than bank branches, began planning a mobile banking strategy in FY13. “Considering the time consumers spend online, they want to bank with us anytime and anywhere, as opposed to just anytime, which was the case with ATMs,” he says.

Besides, customers, increasingly used to the fluidity of service apps such as Uber and Amazon, want banking simple enough to do in three taps. Yes, every bank worth its name has an app, but how many of them are used regularly? Users find many of these clunky and unfriendly. Think of these as the first generation of banking apps.

In a bid to stay relevant to existing customers and appeal to the next generation, banks are investing in app design and development to create products that will be as convenient and easy to use as any service app. And secure, as befits a bank app. That is the future, when apps will be sophisticated enough to be a bank’s core distribution channel.

“To be able to create, and recognise the fact that a 5” screen meant that the real estate that banks had at their disposal to improve user experience was fairly tight,” Anand says. Axis Bank, over the years has been working with an Australian designer and a Singapore-based company for their mobile platform. “I think design is not something that comes intuitively to bankers,” he says, with a wry smile.

Then, there’s ICICI, which introduced Madhivanan Balakrishnan as its chief technology and digital officer. In a letter to employees, ICICI Bank’s managing director and CEO, Chanda Kochhar, said Balakrishnan would “work solely on improving the bank’s digital reach and the technology it offers to its customers and employees”, and help the bank with its “digital agenda”. Balakrishnan is a votary of banking apps. “I think they will continue to be the medium to reach out to customers, and better versions of apps will continue to come in.” He says that future banking products to be offered on apps will include “payments, financial services, lending to some extent, and some basic investments like general insurance”.

Few banks are willing to discuss how much has been earmarked for technological expansion in retail banking. The constant refrain is that it’s difficult to plan long-term, since technology is changing so rapidly. Today, it’s all about digitisation and mobile; tomorrow, it could well be about 3D. We don’t know. And that element of guesswork is what is keeping banks from drawing up long-term technology plans. That said, banks are happy to spend to improve the technology experience over the next five years or so; staying away is no answer, because that’s where customers are going.

As Deepak Sharma, chief digital officer for India’s fourth-largest private lender Kotak Mahindra Bank, says, “Digital is still a growth strategy for us. We’re not looking for returns yet. Besides, we’re still investing in branches. So you can imagine the increase in expenditure for the bank right now.”

For HDFC Bank, a leading private sector lender, close to 63% of all transactions happen over the Internet, including mobile. This was 44% in FY13, and 13% a decade ago. So, while the shift of 13% to 44% took eight years, 44% to 63% has happened in just two. “That tells you that customer behaviour is changing a lot,” says Nitin Chugh, senior executive vice president and head of digital banking at HDFC Bank. Chugh’s job is to create HDFC Bank’s digital strategy, come up with new banking products, and tie up with technology companies and startups for new ideas.

“Today’s consumers aren’t learning online behaviour from banks, they’re learning it from online businesses; the Amazons and Flipkarts,” says Kotak’s Sharma. “I honestly think banks are no longer financial services, they’re consumer businesses.”

According to RBI data, in May 2016 alone, mobile banking transactions—whether smartphone browsers or apps—were worth Rs 74.3 crore; transactions on mobile wallets stood at Rs 2.4 crore. While the share of mobile wallets is small today, it’s likely to grow as more people see value in peer-to-peer transfers and cashless transactions. That, in turn, could hit the pure payments business of banks—unless the banks get their act together and start using technology to woo customers.

A recent Motilal Oswal report on digital banking explains that “transaction convenience will determine transaction frequency and consequently, CASA (current account savings account) market share over the next five years. Banks that improve their share of transactions (by offering greater convenience) will command a higher share of the low-cost CASA deposits.”

Not all bankers see apps as the future. SBI’s chief digital officer Shiv Kumar Bhasin says the frenzy around apps is “a short-term buzz” at best. “This isn’t dramatically changing the life of customers. So I’m not a fan of these apps.” Instead, what he’s doing at SBI is setting up the foundation for future technological growth. “For the last 12-18 months, I’ve been working on fixing the robustness and stability of networks on which the bank runs,” he says. Bhasin took up this job in July 2014. “SBI worked on a point-to-point network with no backups if communication lines went down. Now, we’re installing the largest private cloud network by any bank in the world, which will run 125,000 virtual machines.”

SBI has budgeted Rs 6,000 crore a year to invest in technology. Bhasin has been upgrading SBI’s woefully poor 64 Kbps Internet connections between branches to a 2 Mbps one, replacing servers connecting a branch to core banking with a cloud connection, and investing in a 15,000 sq. ft. data centre.

ICICI is also investing in technology platforms, apart from launching apps. One of Balakrishnan’s focus areas will be on using blockchain—the distributed public ledger—to make their banking infrastructure more “robust and secure”.

“Blockchain is a technology we cannot stay away from,” says Balakrishnan. Perhaps, he adds, blockchain could help in getting KYC requirements fulfilled faster. ICICI, says Balakrishnan, is talking to fintech companies, the NSE, and other banks to bring them on board and experiment with blockchain together, much like the R3 ECV consortium of banks globally. “There’s no advantage to implementing it on your own. We’re experimenting with technology use cases to build data on a public ledger format.”

Along with developments in financial technology, what is really changing banking is Aadhaar. The programme “is an electronic KYC [know your customer, or information that every bank is supposed to have on its customers]”, Nandan Nilekani told Fortune India back in 2014, soon after he stepped down as chairman of UIDAI, the government body tasked with implementing Aadhaar. It serves as a foolproof (well, almost) means of identification since it’s backed by biometrics. Small fingerprint scanners are easy to use and inexpensive, and can be installed at unlikely locations (such as kirana stores).

Earlier this year, delivering the keynote at the 2016 ThinkNext talks organised by Microsoft, Nilekani shared details of how Aadhaar helped financial inclusion. He said “270 million bank accounts linked to Aadhaar today have transmitted Rs 35,000 crore into people’s bank accounts electronically in real time across eight government programmes”.

As DBS Bank has shown, Aadhaar need not help only the unbanked or in direct transfer of government benefits. “The trinity of Aadhaar, smartphones, and a vastly spread out retail network offers a platform with the lowest cost structure,” says Srikanth Nadhamuni, co-founder of Novopay, and former head of technology, UIDAI. More than half the population is unbanked, and some 900 million-plus don’t use smartphones. “They need a bridge before they move up to become smartphone users,” says Nadhamuni. “Retail outlets are that least-cost bridge.” The opportunity is huge, with over 50 million small stores estimated to be thriving on low margins.

In a recent interview to Fortune India, Nilekani calls this the “assisted service” model, which is also the model for much of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s much-vaunted Digital India initiative. This is “the PCO/STD [public call office/ subscriber trunk dialling] model of 20 years back. From the one end, [better] connectivity [4G] will get deeper because of more phones, but even before that there is the chance to build a market for those who don’t have access through the ‘assisted model’.”

Together, Aadhaar, smartphones, and a network of sales points will also drive payments banks. The idea of these banks is to provide banking services to those who are too far away from the traditional bank networks. A payments bank needs no infrastructure, just a network of banking correspondents who visit far-flung hamlets and hand out cash or accept deposits (up to Rs 1 lakh). Account-holders can verify their accounts using Aadhaar and biometrics. All very like what Novopay is doing. Incidentally, Novopay had applied for a payments bank licence, but didn’t get it. Today, its app is likely to make things that much more complex for a payments bank such as Paytm.

SAURABH TRIPATHI, PARTNER, at Boston Consulting Group, who heads the financial services practice and has consulted on several ‘digital transformation’ projects, says the second wave of digital banking will use more “complicated data and predictive analytics”, creating more sophisticated banking products. “Financial services should be the backbone, the undercurrent, of all consumer behaviour. That is truly a digital bank.”

Axis Bank’s Anand cites the example of Apple Inc. coming up with biometric verification which banks would use to verify mobile-originated transactions. While customer expectations evolve rapidly, technology is also changing at a crazy pace. “So you’ve got to keep track of what technologies are available, quickly find use cases for your customers, and be able to create those solutions,” says Anand.

It’s what the DBS digibank is trying to do; its bank is powered by Kasisto, a “virtual assistant” or chatbot, developed by the same people who developed Siri.

The point Tripathi is making is more nuanced: that there is a difference between digitising and going digital. The former is basic, involving putting a bank’s established processes online. The latter takes time; it’s about a bank figuring out how technology can help it across the value chain.

And that’s why banks are now trying to source information on their customers from the places they spend time online. This led to the birth of social media banking that allowed customers to contact their bank or even transfer money to their social media contacts on networks like Facebook and Twitter. Last year, Axis Bank introduced PingPay, an app built over major social media messaging platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Even SBI, with an app-averse Bhasin heading tech, launched SBI Mingle, a social media banking platform for small banking requests. As Kochhar told Fortune India in an earlier interview: “We will have to ride on the trends on which our consumers are riding ... digitisation, mobility, and social media.”

There are other innovations as well. Earlier this year, Axis Bank tied up with GOQii, the digital health and wellness startup which focusses on wearable technology. The plan is to insert a MasterCard payment chip inside the GOQii fitness band, and if the customer walks say 50,000 steps per week, Axis Bank will reward him with loyalty points. The next logical step would be to share the customer’s wellness data with health insurance partners to source a discount on his health insurance. “That’s where we’re integrating technology with banking,” says Anand.

But banks have not been the ones pushing technological change, claims Deepak Shenoy, co-founder of Capital Minds, a company that mines financial data and provides analytics. “From core banking, to IMPS and NEFT, to UPI [unified payments interface], it’s really the Reserve Bank of India that has been bringing technological change to the banking system.”

Technology is not just about creating the best app. As SBI’s Bhasin knows, it’s about building a robust yet flexible framework that will allow technological innovation in future. And for that, data warehouses or data lakes are indispensable, says Anup Pai, co-founder of Bengaluru-based Fintellix, which sells software to financial services companies in India and the U.S.

“The biggest problem right now is that records are still fragmented,” Pai explains. With banks collecting millions of data points on their customers from disparate sources, they often build multiple profiles of the same customer in different parts of the database. “What is needed is that banks integrate all this information in one area, from where anyone in the bank can draw data.” Many banks, he says, have not started investing in this. HDFC Bank seems a notable exception, having made “the fastest progress in this”.

At Kotak Bank, Sharma says it’s not such a big deal. Data warehousing is for Big Data, he says. “The new trend in [developed] markets is not to look at Big Data, but to look at smaller, finer details, and make a profile of the customer,” he says. “There’s a debate going on, but it’s acknowledged that after a while, Big Data can only give you those large-scale insights. You need to dig for smaller bits of data to get a more realistic picture of your customer,” he says.

—Additional reporting by Kunal N. Talgeri

A version of this article appears in the Aug. 2016 issue of Fortune India.